Since Betsy DeVos became the secretary of the U.S. Department of Education, she has continued to push for a federally funded private school voucher program. These programs currently exist in 29 states and provide state support—through direct payments or tax credits—for students to attend private schools. (see text box) Voucher supporters such as Secretary DeVos describe vouchers as providing parents with freedom of choice in education. However, some states have historically used private school voucher programs as a means to avoid racially integrating schools, as occurred during the 1950s and 1960s.1 More recently, evidence has shown that these programs are not effective at improving educational achievement.2 Recent evaluations of certain voucher programs have shown no improvement in achievement or a decline in achievement for students who use them. For example, a Center for American Progress analysis found that the overall effect of the D.C. voucher program on students’ math achievement is equivalent to missing 68 days of school.3 Voucher programs are also not a viable solution in many rural areas of the country because these programs can strain funding resources in communities that already have lower densities of students and schools.4 Public funding should be used to ensure that all students have access to a quality public education, but voucher programs divert funding away from public schools. There have been a number of reports detailing how voucher programs provide public funding to schools that can legally remove or refuse to serve certain students altogether.5 This issue brief provides a comprehensive analysis of the various ways that voucher programs fail to provide the civil rights protections that students have in public schools.

In August 2018, a viral video showed a young child trying to enter a private school while a teacher repeatedly refused entrance to him and his father.6 In the video, the child looks on in pure confusion as a teacher explains that his loc’d hair violates the school’s dress code. The dress code allegedly required that boys have hair no longer than their chin. Clinton Stanley Sr. and his son, Clinton Stanley Jr., were not informed of this rule when they signed up to attend the school, and they were refused admission when they arrived.7 Unfortunately, similar events happen in public and private schools across the country. However, in a public school, parents and children have more avenues of recourse when they feel that they are experiencing discrimination, including filing complaints with the school district or the state’s education agency. While public school systems must accept and educate all students, private schools—even those that accept public support through vouchers or other state or federal programming—may refuse to serve certain students, with limited options for parents advocate for their children.8

In this issue brief, the authors outline various ways that discrimination can occur in private schools that accept public support through private school voucher programs.

Various types of voucher programs

Private school voucher programs provide public funding to private schools. There are three different types of private school voucher programs:

- Traditional private school vouchers provide public money to parents to pay for tuition at private schools.

- Education savings accounts place public funding in an account for parents to use for education expenses.

- Tax credit scholarships provide tax credits to individuals and corporations that donate to organizations providing scholarships for students to attend private school.

The inherent civil rights risk of vouchers

When students participate in a voucher program, the rights that they have in public school do not automatically transfer with them to their private school. Private schools may expel or deny admission to certain students without repercussion and with limited recourse for the aggrieved student. In light of Secretary DeVos’ push to create a federal voucher program, it is crucial that parents and policymakers alike understand the ways that private schools can discriminate against students, even while accepting public funding. Parents want the best education possible for their children, and voucher programs may seem like a path to a better education for children whose families have limited options. However, parents deserve clear and complete information about the risks of using voucher programs, including the loss of procedural safeguards available to students in public schools.

The state of U.S. voucher programs

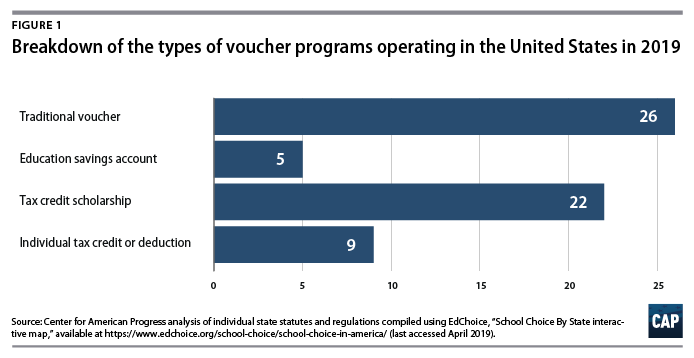

There are currently 62 voucher programs operating in the United States across 29 states. Figure 1 provides a breakdown of all of the voucher programs currently operating across the country. Traditional voucher programs and tax credit scholarships are the most common. (see text box)

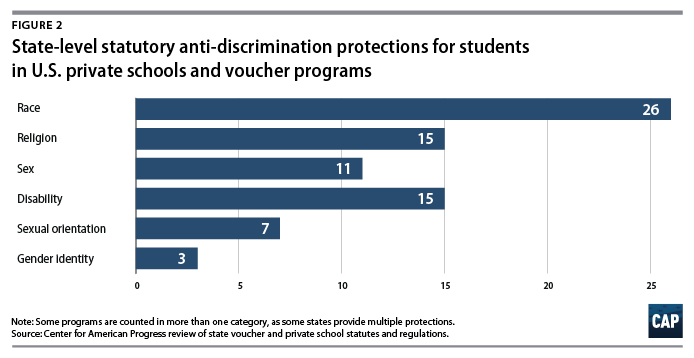

According to the authors’ analysis of the statutes and regulations governing voucher programs and state private schools, less than half of the currently operating voucher programs provide statutory protections for racial discrimination. (see Figure 2) Even fewer states provide these protections for students based on religion, sex, disability status, sexual orientation, and gender identity. Some states incorporate federal anti-discrimination language, such as Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, 42 USC § 2000(d), into their voucher program statutes.9 (see Appendix) The authors determined that these states do not provide sufficient protections for students. The use of federal anti-discrimination language attaches students’ civil rights protections to whether or not their private school receives federal funding. School funding resources add a layer of complexity because some private schools do not receive any state or federal funding. Therefore, the best way to ensure that students have unambiguous and explicit anti-discrimination protections is to enumerate them in the statute creating the voucher program or in state laws governing private schools. Ten of the programs analyzed fail to provide any statutory protections against discrimination for students.

Even with explicit statutory state protections against discrimination, private schools can fail to serve certain students. Below, the authors address the various ways that private schools can expel or treat students in a discriminatory manner.

Racially discriminatory dress code policies

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 bars any school that receives federal funds from discriminating against students on the basis of “race, color, or national origin.”10 The IRS also requires that private schools adopt racially nondiscriminatory policies to receive and maintain 501(c)(3) nonprofit status.11 Title VI binds public schools and private schools that accept any form of federal funding. Therefore, private schools that explicitly discriminate on the basis of race may lose all of their federal funding as well as their tax-exempt status. However, there are also policies and rules that may appear racially neutral but still have the effect of targeting specific groups of students on implementation. For example, a school dress code may prohibit cornrows, braids, or extensions, which may appear to be simply a hairstyle choice. These styles, however, are often meant to protect the tightly coiled hair typically found among people who identify as black or Latinx.12 Implementing these types of restrictions has the effect of removing students from their learning environment or making them feel unwelcome at school. Hair that school administrators deem “unnatural” or “distracting” may have a different context for people from different cultural backgrounds.13

When students are removed from private school because their hair does not conform to the dress code, parents have two options: alter their child’s hair or find another school. In the aforementioned case of Clinton Stanley Sr., a second private school refused to admit his son, citing a hair dress code, even though both schools received public funds through Florida’s Tax Credit Scholarship Program.14 Stanley Sr. had to take his son to the local public school to ensure that he would not miss out on an education.15 Another Florida student, Vanessa Van Dyke, is now being homeschooled after she was pushed out of the private school that she attended through a voucher program because she refused to straighten or cut her tightly coiled hair. In an interview with the authors, Van Dyke stated, “Even though my experience was really tough, I encourage other students to be themselves and not change themselves to stay in a school or for anything else.”16

Of course, public schools can also have dress code requirements, and students have sometimes been disciplined in public school for the way they wear their hair.17 However, there are more avenues of redress for parents and students in public schools. These include filing a complaint for discrimination with their state’s education department, a civil rights complaint to the U.S. Department of Education, or a civil lawsuit. In 2017, for example, the Massachusetts attorney general demanded that a public charter school stop enforcing its unlawful hair policy after two African American sisters were suspended for wearing hair extensions.18 Students attending a private school are much less likely to have a clear avenue for challenging their school’s dress code. As in the cases of Clinton Stanley Jr. and Vanessa Van Dyke, students’ only choices may be to comply with dress code restrictions on hairstyles—even if it means altering their hair from its natural state—or to find another school to attend.

Using vouchers to avoid integration

In response to federal desegregation orders following Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Prince Edward County, Virginia, slashed its education budget and then closed its public schools altogether in 1959.19 Local officials worked with the Virginia General Assembly to create a tuition grant program that allocated vouchers to white students to attend segregated private schools or other nearby public schools.20 This course of events in Prince Edward County provided a blueprint for other communities to avoid integration efforts. By the end of the 1960s, more than 200 private segregation academies had opened in the South, relying on vouchers to cover significant percentages of student tuition as well as on other state resources to operate.21

Lack of educational protections for students with disabilities

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) requires state and local education agencies to provide a free appropriate public education (FAPE) for disabled students in the least restrictive environment.22 Under IDEA, public schools must develop an individualized education program (IEP) for every disabled student that outlines the services and supports necessary to meet the student’s learning needs.23 The school must then provide the services and accommodations identified in the IEP. In rare cases, the IEP team might determine that the best way to provide students with a FAPE is to place them in a private school at the school district’s expense. In these cases, students retain all of their IDEA protections in the private school.24 However, when disabled students use publicly funded vouchers to attend a private school, they are considered “parentally placed private school children” under IDEA and are subject to a different set of protections.25

The special education services that children receive when using a voucher vary from state to state. There are some states that allow students to retain full IDEA rights when they accept a publicly funded voucher.26 Other states require parents to waive all rights under IDEA, and some states fall somewhere in between.27 This requirement should be of particular concern to parents because it means that private schools can accept public funding while failing to adequately serve disabled students.28 In certain situations, parents are not informed that they are forfeiting their child’s rights under IDEA when they sign up to participate in a voucher program for disabled students.29 A school could, for example, completely disregard any evaluations or diagnostics pertaining to a child’s disability.

In public schools, IDEA sets forth due process protections that allow parents to challenge decisions made by the school on a range of issues from disciplinary actions, to services and accommodations, to the amount of time the child spends in a mainstream classroom.30 However, these rights do not automatically transfer to private schools participating in a publicly funded voucher program, and some programs may specifically revoke them.31 If a voucher program requires parents to waive their child’s IDEA rights, there are very few avenues of recourse if their child’s needs are not being met.32 Parents can either accept the services they are receiving, or remove their child from the school.33

Denying admission to other religious groups

The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution sets forth that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”34 Under this amendment, students attending public school are free to express their faith and may not be turned away from an education due to their religion. Additionally, Title VI of the Civil Rights Act prohibits discrimination against students on the basis of national origin, which the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights (OCR) has interpreted to include protections from religious discrimination stemming from perceived ethnic identity or country of origin.35

It is unlawful for public schools to refuse admission to students because of their religion or to require them to learn and adhere to one faith.36 Religious private schools, however, can deny admission to students who come from a faith background that is different from the affiliation of the school. Even if these students are admitted, they must adhere to the religious tenets of the school they are attending. This can effectively eliminate choices for many parents in places where the vast majority of schools participating in the state voucher program fall under one religious group.37 For example, in Indiana, more than 90 percent of the schools participating in the state voucher program are Christian schools.38 There are some voucher programs, such as the D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program, that require participating schools to admit all students regardless of their religion.39 In cases where these explicit legal protections do not exist, however, parents who do not observe the same faith as the admitting school but would like to use a voucher have limited options.

Sex-based discrimination

Title IX is a section of the federal Education Amendments of 1972. Title IX prohibits discrimination on the basis of sex in any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.40 Sex-based discrimination has been interpreted to include sex-based stereotyping and, by a growing number of federal courts, discrimination on the basis of gender identity and sexual orientation.41 However, private schools that do not take federal money—or do take federal money but receive an exemption on the grounds of conflict with their religious tenets—do not have to be Title IX compliant.42 Therefore, students who use vouchers could attend private schools that legally discriminate on the basis of sex. For example, in Virginia, a private Christian elementary school told the grandparents of Sunnie Kahle that it would deny her enrollment the following year if she did not change her haircut and dress to better suit her “God-ordained identity” as female.43 In Indiana, administrators at Cathedral High School refused to recognize the transition of a transgender student. The school continued to identify him as female and use his dead name, the name he used before his transition, in official school documents and programs.44

The aforementioned private schools are able to discriminate against students because they do not receive federal funding and thus are exempt from Title IX. However, even in cases where private schools do receive federal funding, many of them are able to claim an exemption to Title IX protections on the basis of religious tenets.45

State-level anti-discrimination laws also might not offer protections to students receiving vouchers to attend private schools.46 In fact, the authors’ analysis of the 62 state voucher programs found that only 11 of them, or 18 percent, included state-specific language against sex-based discrimination. Additionally, just seven programs, or 11 percent, enumerated state-specific protections against discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation, and only three programs, or 5 percent, included protections for gender identity. In summary, students at private schools that are both exempt from Title IX and do not face any state requirements for sex-based discrimination protections have limited legal recourse if they experience discrimination.

In contrast, students in all public educational institutions are protected against sex-based discrimination under Title IX; in some states, students are protected by state anti-discrimination and anti-bullying laws as well.47 If students believe that they have experienced sex-based discrimination, they have several avenues for recourse. For example, they could report the acts of discrimination to the school district employee responsible for coordinating compliance with Title IX. All public schools are legally required to have a Title IX coordinator and are responsible for addressing Title IX violations through a grievance procedure or risk losing federal funding.48 Additionally, students or someone on their behalf can file a complaint with the U.S. Department of Education’s OCR within 180 days of the most recent act of discrimination.49 Finally, students or someone on their behalf may file a Title IX lawsuit against their school district or educational institution.50 In states with anti-discrimination laws, students can follow similar avenues of recourse, but with regard to the violation of their rights under the state’s laws.51 Even though public school students can still face sex-based discrimination and the Trump administration has rescinded guidance intended to protect transgender students’ rights under Title IX, students in schools covered by Title IX have more legal options than students in Title IX-exempt private schools.

Conclusion

There are many costs associated with private school voucher programs, including negative effects on learning and the draining of public money away from public schools. Yet, as explored in this issue brief, an additional cost of accepting publicly funded private school vouchers may be the loss of students’ civil rights. Public money should be used to serve all of the public, and any schools that receive public investment must be required to protect the civil rights of all students. In the 1950s and 1960s, some states created private school voucher programs with the specific intent of maintaining segregation in schools. While today’s voucher programs have different aims, they still may not protect the civil rights of children who are most at risk of discrimination. Voucher programs are not a viable school choice option if they fail to adequately serve and protect the rights of students. Therefore, states should not create any new voucher programs and should avoid expanding existing programs. In states where voucher programs are currently operating, government officials should ensure that public funds are not being used to endorse discrimination. Voucher programs must come with explicit state-level protections for all students as well as a plan to enforce those protections.

Furthermore, parents and guardians deserve the right to make an informed decision about their child’s learning environment, and there should be avenues for them to protect their child when they have experienced discrimination. State and local education agencies must provide information to families who are considering participating in a voucher program, including full disclosure about policies that may push their child out of school. Children deserve to feel welcome and accepted in their learning environment. If private school voucher programs are going to exist, they must be open to accepting all students, and they must include the same protections and avenues of recourse that exist for students attending public schools.

Bayliss Fiddiman is a senior policy analyst for K-12 Education Policy at the Center for American Progress. Jessica Yin is a special assistant for K-12 Education Policy at the Center.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Mary O’Connell, professor emerita at Northeastern University School of Law, for her review of the legal analysis. They would also like to thank their colleagues at the Center for American Progress who provided valuable input and feedback on this brief: Connor Maxwell, Emily London, Sharita Gruberg, Caitlin Rooney, Rebecca Cokley, Azza Altiraifi, and Valerie Novack.

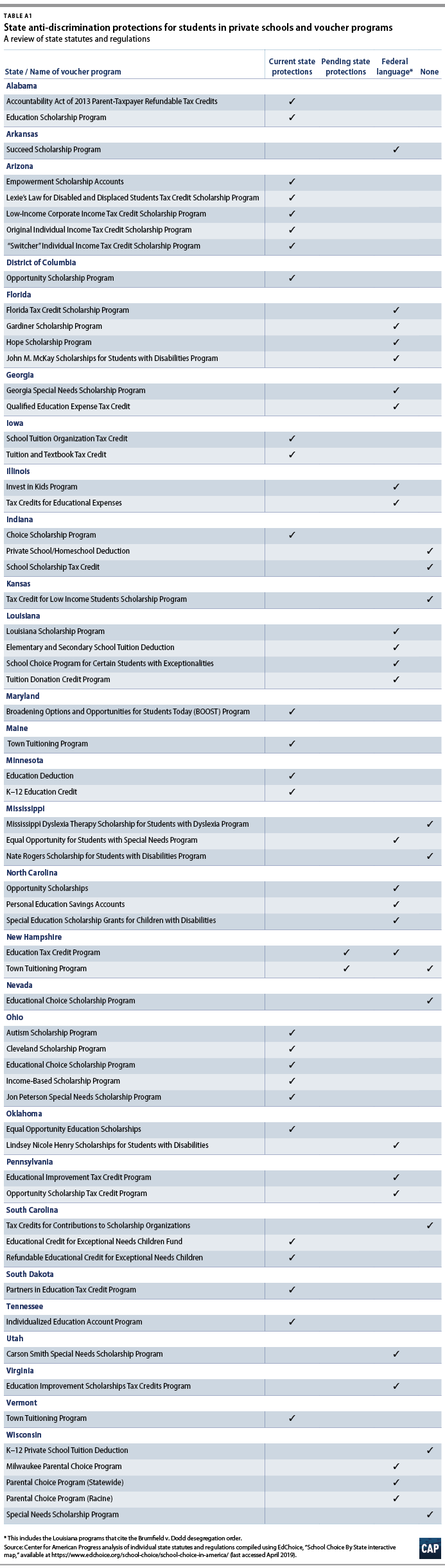

Appendix

The authors conducted an analysis of state statutes and regulations governing voucher programs, private schools, and human rights to identify anti-discrimination protections for students attending private schools through voucher programs. States that incorporated federal anti-civil rights language were placed in a separate category from states that provided state-level protections unattached to federal funding.