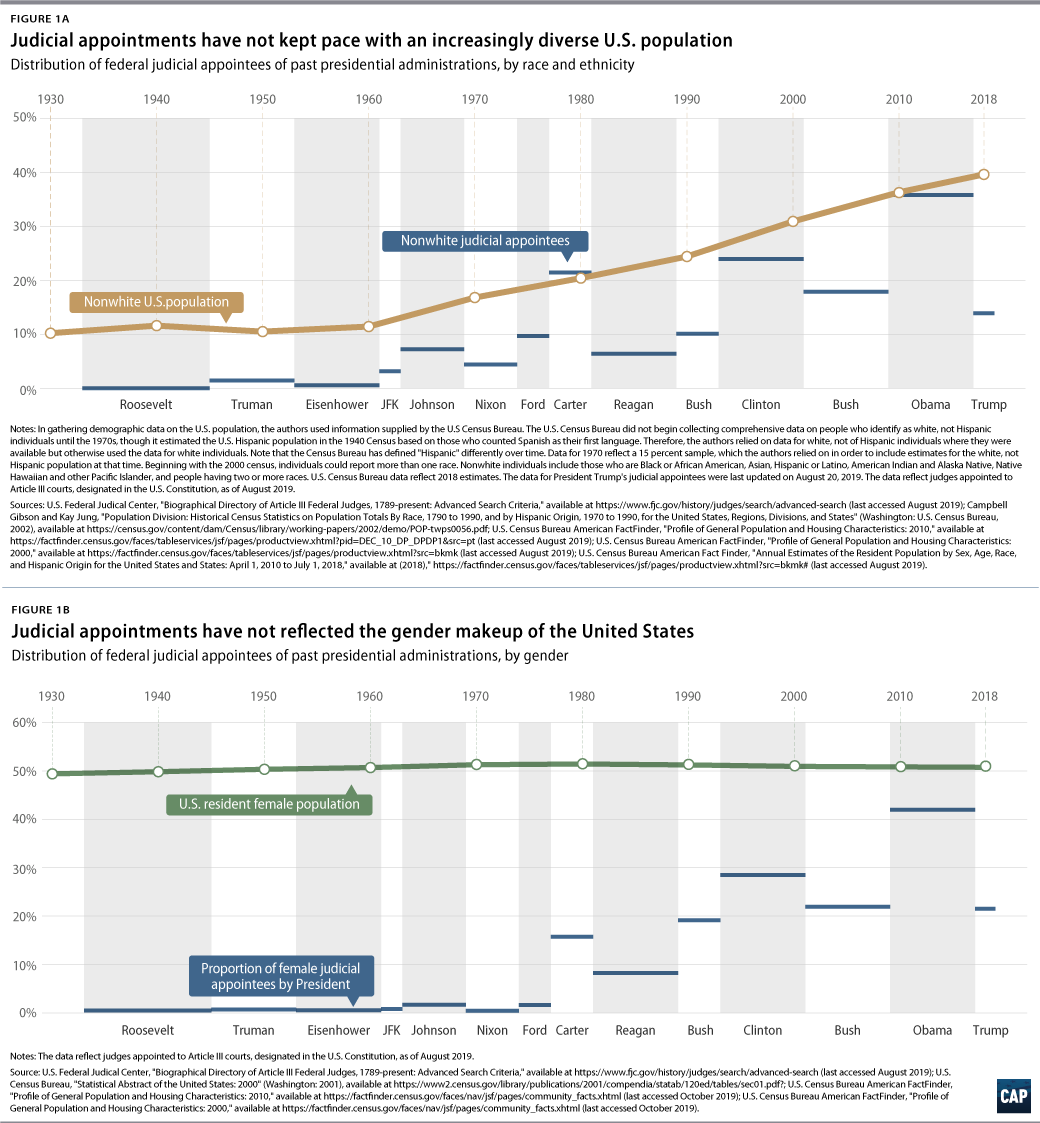

Since the nation’s founding, the federal judiciary has been overwhelming white and male. From the 18th century until the 1960s, white male judges comprised at least 99 percent of the federal judiciary.12 A woman was not appointed to an Article III judgeship until 1934 under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and it was not until 1949, under President Harry S. Truman, that an African American was appointed to a federal circuit court.13 On the Supreme Court, racial and gender diversity came even later: Justice Thurgood Marshall—the first African American justice—was appointed in 1967, while the first woman on the court, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, was not appointed until 1981.14 Judge Deborah A. Batts—the first openly LGBTQ federal judge—was not appointed until 1994.15

Examining diversity among sitting or active judges

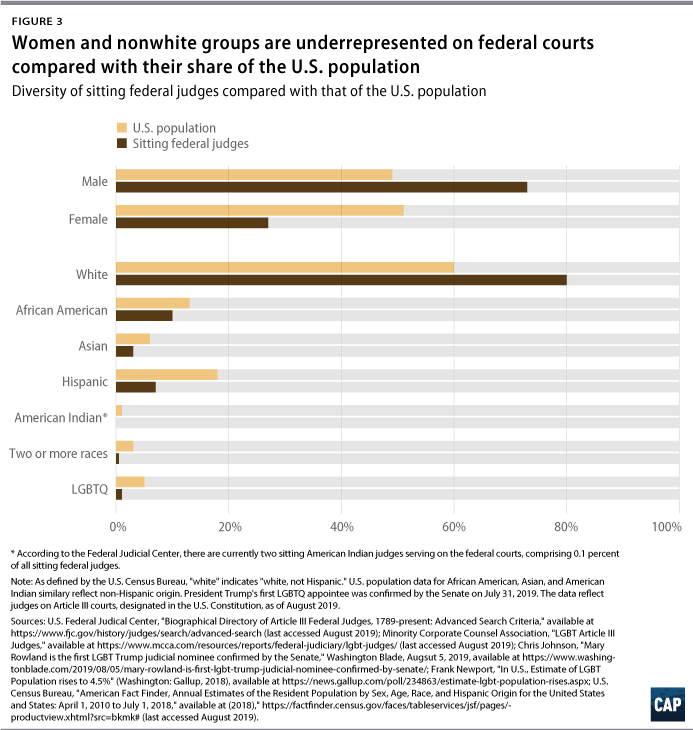

Diversity in the federal judiciary can be measured by looking at “sitting” or “active” judges. The dataset for sitting judges includes those serving in senior status, which is a form of semi-retirement. Datasets for active judges, on the other hand, do not include senior status judges and only reflect judges who serve on the courts full time. Because judges in senior status can still hear cases, the authors have included them in this analysis. According to the federal courts’ official website, senior status judges “typically handle about 15 percent of the federal courts’ workload annually.”16 Due largely to the Obama administration’s efforts to appoint more people of color, women, and LGBTQ individuals to the federal bench, diversity statistics are somewhat better among active judges—who tend to be younger and more recently appointed—than among sitting judges. That said, even among active judges, representation of underrepresented groups is quite poor. For instance, white male judges make up 59 percent of all sitting judges and nearly half of all active judges.

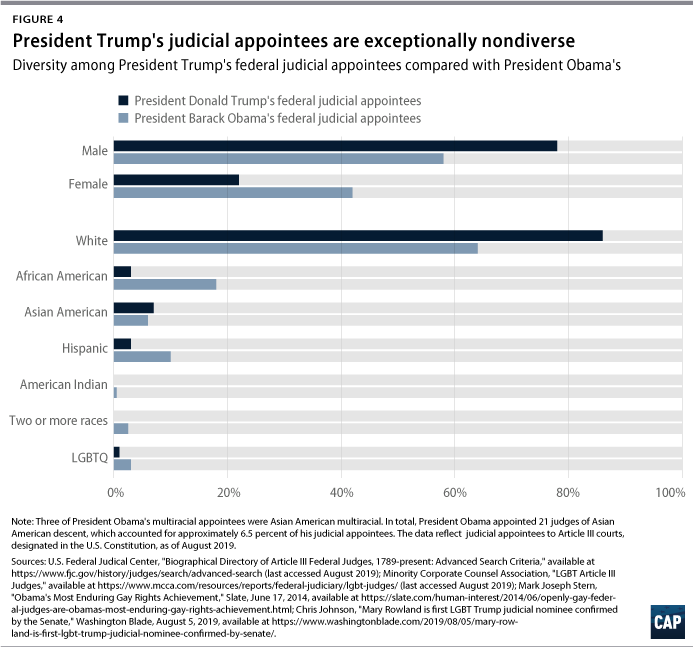

Although judicial diversity has improved in recent years—thanks, in particular, to efforts by former Presidents Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama—federal courts remain dominated by judges who are white and male. As of August 2019, 80 percent of all the sitting judges on the federal bench were white and 73 percent were male. Together, white males comprise nearly 60 percent of all judges currently sitting on the federal bench.17 Meanwhile, people of color—including those belonging to two or more races—and women make up only about 20 percent and 27 percent of sitting judges, respectively, while individuals self-identifying as LGBTQ comprise fewer than 1 percent of all sitting judges.18 To put this into perspective, people of color make up nearly 40 percent, women make up 51 percent, and people identifying as LGBTQ comprise approximately 4.5 percent of people living in the United States.

Of judges currently sitting on federal Article III courts, only about 10 percent are African American and 2.6 percent are Asian American. These numbers do not track with the U.S. population. For example, Blacks and African Americans comprise 12.5 percent of the U.S. population, while Asians make up 5.7 percent of the population. Hispanics are even more significantly underrepresented on the courts compared with their share of the population: Only 6.6 percent of sitting federal judges are Hispanic, despite the fact that this group comprises 18.3 percent of the U.S. population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.19 And there are only two American Indian judges sitting on the federal bench, making up just 0.1 percent of the federal judiciary compared with 0.7 percent of the U.S. population.20

If one narrows the pool to just active federal judges, which does not include judges in senior status, the numbers improve—but only marginally. Among active judges, nearly 73 percent are white and 67 percent are male. White males comprise 50 percent of all active federal judges. On the other hand, people of color comprise 27 percent and women represent 33 percent of active federal judges. Approximately 13 percent of active federal judges are African American, while 4 percent are Asian American and 9 percent are Hispanic.21 Among judges actively serving on the federal courts, only one is American Indian. In all, people of color comprise just 27 percent of actively serving judges. Meanwhile, LGBTQ people make up approximately 1.4 percent of active judges.22

It can be difficult to acquire up-to-date information on the religious affiliations of federal judges, as they may not openly disclose which faith—if any—they adhere to. However, a 2017 study by scholars Sepehr Shahshahani and Lawrence J. Liu found that among federal appellate judges, 45.1 percent were Protestant, 28.2 percent were Catholic, 19 percent were Jewish, and 5.1 percent were Mormon.23 Strikingly, Hindu judges comprised just 0.5 percent of federal appellate judges, and the study’s authors were unable to identify any Buddhist, Muslim, or atheist federal appellate judges. In 2016, then-President Obama nominated Abid Riaz Qureshi to the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. Quareshi would have been the first Muslim American federal judge, but the Senate failed to confirm his appointment.24

Regrettably, the authors were unable to locate any publicly available data on the number of sitting federal judges with disabilities. The virtual absence of information on disabled federal judges is problematic and deserves more attention.

The federal judiciary also lacks diversity in terms of educational background. A 2016 study found that approximately 48 percent of all former and current federal judges graduated from one of 20 top law schools. Of those, nearly a quarter attended law school at Harvard University, Yale University, University of Michigan, University of Texas, or Columbia University.25 When factoring in judges who attended University of Virginia, Georgetown University, University of Pennsylvania, George Washington University, and Stanford University, this number jumps to 35 percent of all federal judges, past and present. Among Supreme Court justices, in particular, more than 30 percent of those who have served on the court graduated from just one law school: Harvard. In fact, as noted by the study’s authors, “Harvard has had more representation on the Supreme Court than the bottom ninety-five percent of law schools combined.” Just three elite law schools—Harvard, Yale, and Columbia—have been responsible for more than half of all Supreme Court justices who have served on the bench since the nation’s founding.26

Professional diversity is also lacking. A 2017 Congressional Research Service report found that more than 46 percent of active federal circuit court judges were either serving in private practice or as a state or local judge when they were appointed to the federal bench. In comparison, 7.5 percent were working as law professors, 3.7 percent were working for state and local government, and fewer than 1 percent were serving as a public defender.27 Among active district court judges, nearly 66 percent were either working in private practice or serving as a state or local judge. At the same time, only 3 percent were working for state or local government, 1.4 percent were serving as a public defender, and just 0.5 percent were working as a law professor when they were appointed. Having judges with different professional experiences overseeing cases is important because these experiences can shape how judges view the application of the law and individual parties.28 Moreover, a 2016 study by the Alliance for Justice found that roughly 86 percent of judicial nominees under the Obama administration had either worked as corporate attorneys, prosecutors, or both.29 At the same time, fewer than 4 percent had worked as lawyers at public interest organizations.30

Efforts to diversify the federal judiciary have regressed under Trump

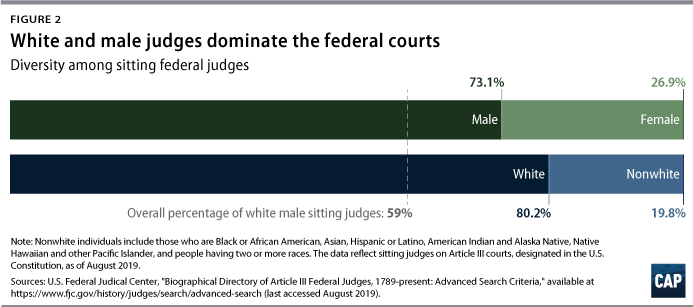

Although other presidents who served during the early to mid-20th century made some efforts to appoint federal judges belonging to historically underrepresented groups, President Jimmy Carter was the first to make diversifying the federal courts a priority. Until Carter entered office, white judges made up at least 90 percent of all judicial appointees in every preceding administration since the nation’s founding. Under Carter, however, judges from racially and ethnically diverse backgrounds comprised more than 21 percent of appointees.31 Of Carter’s judicial appointees, 37 were African American, which amounted to more than three times the number of African American judges appointed by any previous administration.32 Moreover, whereas female judges comprised less than 2 percent of judicial appointees in past administrations, they made up nearly 16 percent of Carter’s judicial appointees.33

In the 1990s, President Bill Clinton took up the mantle left by Carter: Almost half of all of Clinton’s federal judicial appointees were from historically underrepresented groups. Yet no president aimed to diversify the bench more than President Barack Obama. Obama nominated and confirmed more women than any other president in history, although there is still significant room for improvement; by the time he left office in January 2017, nearly 42 percent of his judicial appointees had been women.34 Moreover, people of color comprised nearly 36 percent of Obama’s 324 judicial appointees. In all, more than 60 percent of Obama’s judicial nominees were people of color, women, and sexual or gender minorities.

Unfortunately, any gains in diversity made by previous administrations came to a halt once Trump took office. President Trump is appointing federal judges at a rapid pace, yet his judicial picks are the least racially and ethnically diverse of any presidential administration over the past 30 years. As of August, Trump lagged behind the Obama administration in appointing women by 20 percentage points.35 The current administration’s stunning reshaping of the federal courts undercuts decades-worth of efforts by previous administrations—both Democrat and Republican—to diversify the judiciary.

Since President Ronald Reagan, every president except Trump has made the judiciary more racially and ethnically diverse than the proceeding president of the same party.36 In other words, each Republican president elected after Ronald Reagan appointed judges who were at least equally, if not more, racially and ethnically diverse than those appointed by his Republican predecessor—and the same holds true for Democrats. For example, although President George H.W. Bush did not appoint as many judges of color as Jimmy Carter, he did appoint more than Ronald Reagan. Trump broke this trend, as his appointees are 4 percentage points less racially and ethnically diverse than judges appointed by President George W. Bush.37

As of August 20, 2019, of Trump’s judicial appointees, 78 percent were male and 86 percent were white, with white men comprising 67 percent of Trump appointees.38 Only 21.5 percent of Trump’s appointees were women, while people of color made up fewer than 14 percent of Trump’s federal appointees. Only one of Trump’s appointees openly identifies as LGBTQ.39 Moreover, as of August, Trump had only appointed five African American judges and five Hispanic judges. And although 10 of Trump’s appointees were Asian Americans, he has failed to appoint a single American Indian judge.40

Examining Trump’s judicial nominees is an even better indicator of the lack of priority that the administration has assigned to broadening representation on the bench. Although Trump cannot directly control which of his nominees the Senate ultimately confirms, he has autonomy over whom he nominates. As of July 31, 2019, Trump had nominated 183 judges to the federal bench. Of those, more than 78 percent were men and 84 percent were white. Together, white men made up 67 percent of all Trump judicial nominees at that time. Only seven—3.83 percent—were African American, while just 40—21.86 percent—were women.41 Hispanic and Asian American judges accounted for only five and twelve—2.73 percent and 6.56 percent—of Trump’s nominees, respectively. Not a single American Indian judge has been nominated by Trump, and only two judges—1.09 percent—have been nominated who openly identify as LGBTQ.42

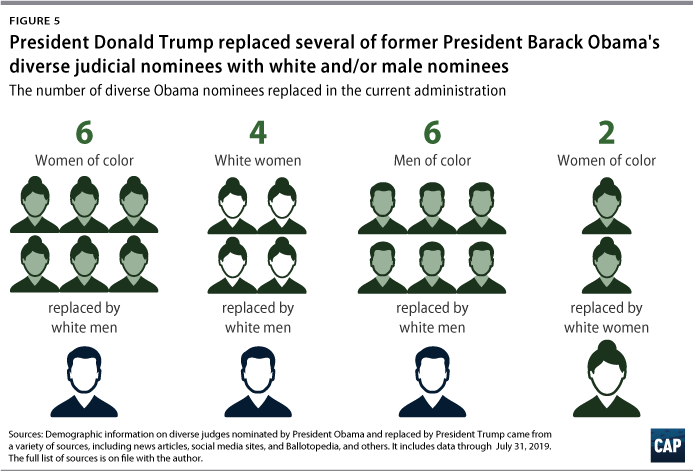

Moreover, when Obama left office in January 2017, more than 50 of his judicial nominees were still pending, many whom were women and/or people of color.43 But instead of renominating Obama’s nominees, once he became president, Trump replaced several of them with nominees who were either white, male, or both.44

Although Trump did end up renominating 13 of Obama’s holdover nominees as of August 2019, seven of them were white males, four were white females, and two were Asian American women.45 There were only a few instances where Trump nominated someone who was more representative in terms of race and ethnicity or gender. For instance, Trump replaced one of Obama’s white male nominees with a white female and replaced one of Obama’s white female nominees with a woman of color. In addition, two white women nominated by Obama were replaced by men of color under Trump.46

Still, Trump’s insistence on nominating and appointing primarily white male judicial candidates, and the Senate’s rush to confirm them, will have profound effects on the country’s legal trajectory and people’s lives.

In considering the courts’ demographic makeup, it is obvious that the federal judiciary is not an equal opportunity employer and instead favors white male elites. This has real consequences for historically underrepresented litigants and parties who may not receive fair or even-handed rulings due to inherent biases among judges. Indeed, a consequence of having such a judiciary is that the public may begin to view the courts as another cog in an already oppressive legal system, rather than as a trustworthy and independent institution.

Also contributing to the public’s distrust of the judiciary is a growing body of evidence showing that certain litigants—mainly people of color—receive disparate treatment when they come before white judges. This treatment has not gone unnoticed.47 A 2014 Pew Research Center survey found that among respondents, 27 percent of whites, 40 percent of Hispanics, and 68 percent of Blacks felt that Black people were treated less fairly by courts, compared with white people.48

Increasing diversity on the federal bench will help address these concerns and foster greater public trust in the judiciary. According to one judge, having a more diverse group of judges that mirrors the makeup of the populace “enhances the ability of the populace to feel that [judges] are more believable.”49 Judicial diversity also offsets discriminatory biases in judicial decision-making. And research shows that the presence of judges belonging to historically underrepresented groups and with different backgrounds can result in fairer judicial outcomes and better courtroom experiences for litigants.

Better descriptive and substantive representation on the bench

The presence of a diverse group of federal judges improves both the descriptive and substantive representation of underrepresented groups on the federal bench.50 As described in CAP’s “Structural Reforms to the Federal Judiciary,” descriptive representation is when an institution physically resembles the population over which it has authority, whereas substantive representation is when an institution acts in the substantive interests of the group over which it presides.51 The latter is, to a degree, less concerned with the physical representation of a group; rather, it is focused on whether the representation is meaningful and embodies the population’s priorities and values.52

Descriptive and substantive representation are not interchangeable

There is a common misconception that descriptive and substantive representation are intrinsically linked. The theory goes that by improving descriptive representation, better substantive representation will automatically follow. But this is not always the case. Judges from underrepresented groups do not take homogenous approaches to how they interpret and apply the law. For instance, not all female judges are pro-choice, in the same way that not all judges of color will rule in favor of affirmative action programs.

As an example, consider Justice Clarence Thomas, the second African American judge confirmed to the Supreme Court. Although Justice Thomas has at times been critical of legal arguments and constructs he perceived as racist, he has also been a staunch opponent of affirmative action programs and has voted to eliminate important voting rights protections that were designed to protect people of color from voter suppression.53 Justice Thomas offers a good lesson against making assumptions about the viewpoints and jurisprudential approaches of judges of color or those from other underrepresented groups. He also presents a good reminder that when it comes to improving the diversity of members of the bench, the United States needs judges who represent underrepresented groups both descriptively and substantively.

Descriptive representation is important, as it improves public trust in the judiciary since people are more likely to trust those with whom they share physical characteristics.54 Therefore, in the interests of both equality and the perception of fairness, it is important that judges reflect the parties and populations they serve. As described by scholars Jason Iuliano and Avery Stewart, “In dispensing justice to all citizens, the legal system cannot allow one demographically homogenous group to hand down decisions while other racial and ethnic groups bear the brunt of those decisions.”55

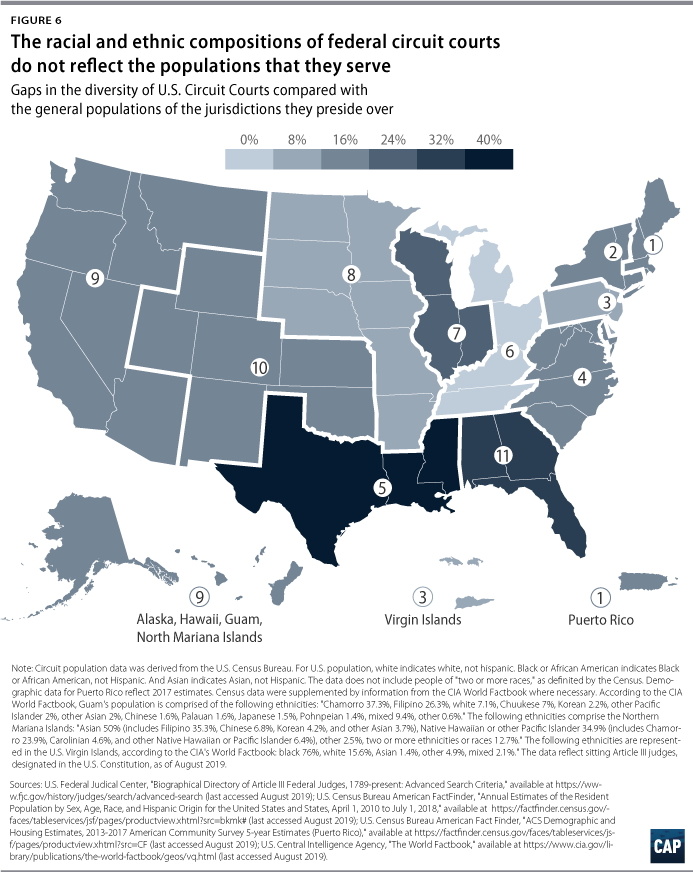

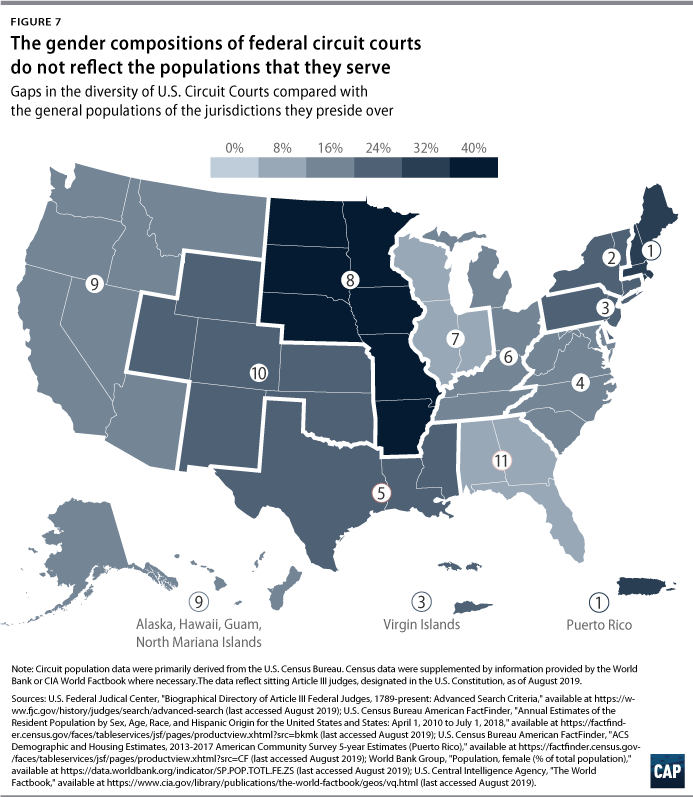

Yet the federal judiciary does not resemble the public at large. As explored in previous sections, notable disparities exist for women, African Americans, Hispanics, Asians Americans, American Indians, and LGBTQ individuals. All of these groups are strikingly underrepresented on the courts compared with their respective shares of the U.S. population.56

The lack of diversity is particularly stark in specific jurisdictions. For example, there are no judges of color sitting on the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals—which includes Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin—even though people of color make up nearly a third of the jurisdiction’s population.57 Meanwhile, of the 18 sitting judges on the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, only one is a woman, even though women comprise more than half of the jurisdiction’s general population. Furthermore, although people of color make up more than 50 percent of the population covered by the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, white judges make up nearly 85 percent of its sitting judges.

But it is not enough to simply nominate and confirm judges who physically represent a variety of races, nationalities, genders, sexual orientations, and any number of additional characteristics. The federal judiciary must be comprised of judges who can identify with the unique experiences of all kinds of litigants who come before the courts. People belonging to underrepresented groups often share a common set of experiences that shape their values and perceptions on certain issues. This allows judges belonging to such groups to effectively champion divergent values and perspectives, thus leading to better substantive representation for those communities. Indeed, as noted by scholar Michael Nava in a 2008 study, judges belonging to historically underrepresented groups tend to be more empathetic and considerate of the concerns of litigants who—like them—have been “similarly ostracized for their differences.”58 Most Americans believe it is important for judges to “be able to empathize with ordinary people.”59

Generally speaking, in the average case where matters disproportionately affecting historically underrepresented groups are not at issue, a judge’s identity—including their race and ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, or religious affiliation—will not have any bearing on the outcome. In other words, for most cases, a female judge will reach the same conclusion as a male judge, a Black judge will reach the same conclusion as a white judge, and so forth. Some studies have even shown that, in certain cases, female judges may issue harsher rulings than their male counterparts against similar litigants.60 One explanation for this is that judges from underrepresented groups feel pressured to rule in such ways so as to avoid being perceived by their colleagues and others within the profession as biased or agenda-driven. As described by a female South Asian immigration judge from the United Kingdom, “The feeling of being an outsider did extend to how I behaved as a judge at first. I felt terribly self-conscious, on guard, needing to make sure I was right and also be seen to be doing it ‘properly.’ So I may even have been harsher than white judges.”61

However, in cases where race, gender, and religion are at issue, a judge’s identity can have a significant impact on how cases are decided. It is worth noting at the outset that studies conducted over the past several decades have reached different—and, at times, even contradictory—conclusions over the extent to which a judge’s identity and background influences their decision-making. That said, a number of studies have shown promising support for the idea that a judge’s background or membership in historically underrepresented groups can affect case outcomes—though more research is needed.

Indeed, judges themselves have recognized that their identities and specific backgrounds can inform their decision-making.62 As noted by Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the differing approaches male and female judges take on cases involving women’s issues: “[T]here are perceptions that we have because we are women. It’s a subtle influence. We can be sensitive to things that are said in draft opinions that (male justices) are not aware can be offensive.”63 Senior Judge Atsushi Wallace Tashima of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, too, has previously described how his life experiences influence his decision-making—particularly the incarceration of his family in a World War II U.S. internment camp for Japanese Americans and Japanese immigrants:

Because we are all creatures of our past, I have no doubt that my life experiences, including the evacuation and internment, have shaped the way I view my job as a federal judge and the skepticism that I sometimes bring to the representations and motives of the other branches of government.64

Studies have found, for example, that female judges are more likely than their male counterparts to rule in favor of plaintiffs in sexual harassment and employment discrimination cases.65 Women judges have also been found more likely to rule statutes unconstitutional if they violate the equal protection, due process, or freedom of association rights of people who identify as LGBTQ.66 Using qualitative analysis, one study found that Asian American judges rule more sympathetically in certain cases, such as those involving matters of immigration or discrimination, which the author attributed in part to the plights that those racial and ethnic groups experienced themselves immigrating to and growing up in the United States.67 Meanwhile, Black judges have been found to be more sympathetic to defendants alleging violations of Fourth Amendment rights than white judges.68

Moreover, plaintiffs alleging racial workplace harassment are 2.9 times more likely to succeed before African American judges than judges belonging to other races and ethnicities.69 According to the study, as a general rule, plaintiffs in workplace harassment cases are more likely to succeed on their claims if they go before a judge of the same race as themselves. In explaining this phenomenon, professors Pat K. Chew and Robert E. Kelley explain:

Judges of each racial group can more readily identify with injustices that happen to their racial group. They draw upon similar life experiences; they know how they would react to being treated in certain ways; and they understand all the subtle “coded” words that carry racial offenses but that others tend to dismiss with “that’s not what I was saying—you’re reading into it.70

By January 20, 2021, more than 200 federal judges will be eligible for senior status.79 Of those 200 judges, more than half are white males. These potential openings provide an opportunity to improve the diversity of the federal bench. But to restore public trust and foster fair judicial outcomes, meaningful reforms must be made to the judicial pipeline and the processes by which judges are appointed.

The recommendations below focus primarily on improving the representation of women and people of color in the federal judiciary, as well as encouraging the nominations and appointments of LGBTQ judges, judges with disabilities, and judges belonging to different faiths. Yet more work is also necessary to improve the representation of judges from different educational and professional backgrounds. Indeed, the recommendations below frequently reference factors that have historically been considered necessary prerequisites for becoming a federal judge—namely, attending an elite law school, clerking for a federal judge, working at a top-tier law firm, and serving as a state judge or U.S. attorney. Preconceived notions that these are the only pathways to becoming a judge must be wholly abandoned if there is any hope of creating a fairer judiciary that is more representative of the population it serves. All judicial nominees, of course, must still have the necessary legal qualifications to adjudicate cases, such as having a healthy understanding of legal and trial procedures, as well as established legal rules and doctrine.

Address the pipeline problem

The lack of diversity within the federal judiciary cannot be remedied without addressing the judicial pipeline problem. Today, too few students of color, LGBTQ students, and students with disabilities are entering law school. And those who are accepted often are not being set up for success, as they face various obstacles in school and in obtaining the kinds of legal jobs that have traditionally led to federal judgeships. At every stage, law students and lawyers belonging to historically underrepresented groups face harassment, discrimination, and negative stereotyping. According to one Asian American female lawyer, “Being an Asian woman added another layer as men were often more interested in expressing themselves as romantic prospects as opposed to colleagues.”80 Attorneys belonging to historically underrepresented groups may also be subject to feelings of isolation. As described in a report by the Minority Corporate Counsel Association on sexual minority attorneys:

Nongay people announce their sexual orientation whenever they mention a date, a spouse, or a child. But these normal conversations can be fraught with tension for lesbians and gay men. If they decide to remain silent about their personal lives … It’s a silence that can often be interpreted by colleagues or clients as distant and cold.81

To improve the diversity of the federal bench, initiatives must be put in place to ensure that individuals from historically underrepresented groups who are interested in pursuing judgeships have the resources and support they need to be admitted to and succeed in law school. Programs must also be established to help candidates obtain prestigious clerkships and law firm jobs, both of which have often been considered unofficial prerequisites for federal judgeships.82 Becoming a state judge, state attorney general, or U.S. attorney are also common points of entry for future federal judges. As such, it is important to prioritize diversity in the pool of applicants in these sectors as well.

Get young people from underrepresented groups interested in judgeships

In order to bring individuals from all different backgrounds into the judicial pipeline, it is necessary to get young people of different races and ethnicities, genders, sexual orientations, and religions excited about pursuing a career in law.

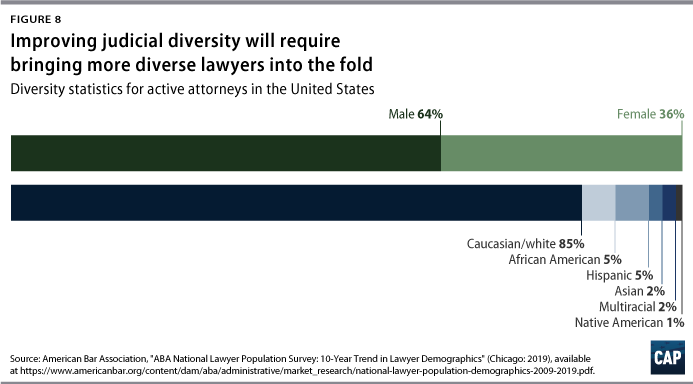

Many people who have family members who are lawyers or judges are inspired to pursue law as a career. This is problematic as a strategy for building a more inclusive judicial pipeline, however, because people from historically underrepresented groups and backgrounds are not well accounted for within the legal profession. For instance, the profession as a whole is roughly 85 percent white and 64 percent male.83 In 2016, the American Bar Association (ABA) reported that only 1.25 percent of its members self-identified as LGBT.84 And a 2011 ABA survey found that fewer than 7 percent of its members responded “yes” to the question, “Do you have a disability?”85 This puts members from underrepresented populations at a disadvantage from the very outset. Indeed, for many young people, having a career as a judge may not be on their radar or believed to be within the realm of possibility.

More outreach must be done at an early age to get young people with different experiences and backgrounds interested in and excited about a career as a judge. Affinity bar associations and other organizations are already leading on this front. The Hispanic National Bar Foundation, for example, has programming—such as the Future Latino Leaders Summer Law Institute—that allows Latino high school students interested in pursuing careers in law to connect with Latino leaders in the legal profession.86 As described by one student participant, “Hearing the success stories of people from similar backgrounds as me has inspired me, and showed me that the legal field is an amazing place for Hispanic people.”87 Meanwhile, groups such as Street Law Inc. and chapters of the Urban Debate League (UDL) work with students in cities to educate them about the law, help them build critical thinking and communication skills, and encourage them to pursue legal careers.88 Street Law Inc. has teamed up with the National Association for Law Placement (NALP) to create a “Legal Diversity Pipeline Program” designed to help excite young people about a career in law. An evaluation of the program found that whereas 46 percent of students reported considering becoming a lawyer before entering the program, that number increased to 65 percent upon completion.89 Moreover, the Silicon Valley UDL partners with local lawyers to provide corporate mentoring opportunities that allow students interested in law to shadow and receive advice and emotional support from practicing lawyers.90

The above groups comprise but a fraction of the vast network of organizations working to foster an interest in law among individuals at an early age. Yet there is always more to be done. For instance, groups offering out-of-state programming should provide scholarships to students of all socio-economic backgrounds who are interested in participating. Such scholarships can go toward application fees, travel costs, and room and board in order to make these opportunities more financially feasible for low-income students. Affinity bar associations and justice-minded organizations can also host events at which high school students are given the opportunity to hear judges of color and women judges, as well as judges representing a variety of other characteristics and experiences, discuss their work in the courtroom and career paths. In addition to driving interest and enthusiasm for the profession among youths, events featuring these judges signal to students of all ages, races, and backgrounds that judgeships are within their grasps.

Make the law school admission process fairer and more accessible

Before becoming a federal judge, one must be admitted to and attend law school. Unfortunately, as described by law professor Sarah E. Redfield in her article on the pipeline to law school, socio-economic barriers often preclude students from underserved communities from competing with their white, affluent peers for admittance to coveted law schools.91 As early as kindergarten, people of color, low-income people, people with disabilities, and other individuals from historically underrepresented groups are disadvantaged in the pursuit of a successful law career due to gaps in the education system.92 For example, schools’ failure to offer accessible educational facilities and equipment can result in education gaps for people with disabilities. Research has shown that the percentage of working-age disabled people who hold a bachelor’s degree or higher is more than 18 percentage points lower than that of nondisabled people.93

In addition to overcoming educational barriers, prospective law students from underserved communities must overcome the significant financial burdens associated with applying for and attending law school. For instance, they must pay to take the LSAT exam—a prerequisite in most states for admission to law school, though a number of law schools now accept GRE scores.94 Although the LSAT offers fee waivers for certain low-income students, they are not always well advertised, and therefore, many students in need may not be aware of their existence. Students who have the financial means can also take LSAT tutoring classes, which can give them a leg up on the exam. These prep classes, however, are expensive. They can cost upward of $1,400, which may be out of reach for low-income students.95

Then there is the application process itself. Each law school application can cost between $60 and $100.96 Because experts recommend applying to between seven and 15 different law schools, the total cost of application fees alone may exceed $1,500.97 Many law schools offer application fee waivers for low-income students, but as with the LSAT waivers, they are not always well advertised and can be difficult to obtain.98

Furthermore, the astronomical cost of attending law school and the prospect of being hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt upon graduation is a major deterrent for some individuals who might otherwise be interested in pursuing a career as a judge. Law school tuition can range anywhere from nearly $12,000 to almost $70,000 per year, depending on the school.99 This is particularly daunting for those who do not have the same financial safety net as their affluent peers. Making matters worse, law students belonging to historically underrepresented groups are statistically less likely to be hired into high-paying positions upon graduation. For instance, women of color represent only about 13.5 percent of associates at U.S. law firms, while the post-graduate employment rate for law school graduates with disabilities is 7.6 percent lower than it is for other graduates.100

By improving education and making it more equitable across communities, a more representative pool of students—across racial, gender, sexual orientation, disability, and socio-economic lines—will enter law school, which starts them on the path to becoming federal judges. The definition of who qualifies for LSAT and law school application fee waivers should be expanded to include more applicants in need. Going further, LSAT-related fees could be waived entirely for former Pell Grant recipients. Private companies offering LSAT test prep should provide low-income applicants with more generous scholarships. For their part, affinity bar associations and justice-oriented organizations can help by establishing scholarship funds to assist low-income students in taking LSAT prep courses and paying the fees associated with the exam—including the costs of travel and lodging if the LSAT testing location is far from home—and with law school applications.

Furthermore, to increase the admission rates for students belonging to historically underrepresented groups, law school must be made more affordable. Additionally, law schools—as well as states and the federal government—must do more to alleviate the massive student debt accrued by their students. Although the federal government offers a federal loan forgiveness program for working in the public interest for 10 years after law school, the program is incredibly difficult to navigate; only 1 percent of program applicants had their loans forgiven under the program in 2018.101 Diversity within the legal profession and among federal judges will not improve unless steps are taken to make law school more financially viable. To address this, some attorneys and politicians have advocated for turning law school into a two-year program, rather than a three-year program.102 An added benefit of shortening law school programs is that new graduates would be able to get practical, hands-on experience sooner than they would if they had to sit through another year of classes, better preparing them for their professional careers.103

For example, to help alleviate the burden of student loan debt, Yale offers a comprehensive loan forgiveness program—the Career Options Assistance Program (COAP)—that allows students making less than a certain amount to forgo payments toward their law school loans. Students making more than the set threshold are only expected to “contribute a portion toward repaying their law school loans, with COAP covering the rest.”104 Unlike many other loan forgiveness plans, COAP applies to graduates working in all sectors, including the public, private, government, and academic sectors. According to the COAP webpage, “Since its inception, more than 1,500 Yale Law School graduates have participated in COAP and received over $54 million in benefits. In 2018 alone, COAP disbursed $5.3 million in benefits to more than 400 graduates.”105

Ensure students from underrepresented groups get into law school

Becoming a federal judge requires more than simply going to any law school. One has to go to the “right” law school. As described in Part I of this report, students’ likelihood of becoming a federal judge drops considerably if they do not attend the nation’s most elite law schools. Regarding the lack of educational diversity among Supreme Court justices, Justice Thomas has said, “I do think we should be concerned that virtually all of us are from two law schools … I’m sure Harvard and Yale are happy, but I think we should be concerned about that.106

This does not bode well for certain applicants of color and applicants from less affluent backgrounds, who, as noted previously, face unique socio-economic barriers that may prevent them from being admitted to these highly selective institutions. In 2015, approximately 58 percent of white law students graduated from the nation’s top-30 law schools, compared with roughly 10 percent of Asian students, 8 percent of Hispanic students, and 5 percent of Black students.107 Law school admission committees may fail to prioritize diversity in their applicant pool, placing too much value on applicants’ LSAT scores and GPAs, which are often lower for low-income applicants and applicants of color compared with wealthy and white applicants, for reasons explained in previous sections.

Law schools—particularly top-tier schools—should give less weight to applicants’ LSAT scores and GPAs. They should also better prioritize diversifying their student body. This may entail doing more outreach to colleges with high enrollments of students of color, women, LGBTQ students, students with disabilities, and students belonging to religious minorities—as well as taking affirmative steps to invite and encourage students from all backgrounds to visit and apply to their schools. Law schools, for instance, should dedicate considerable resources for the purposes of holding regularly occurring “diversity days” for prospective students, with special programming featuring law professors and distinguished alumni—especially judges—with a variety of personal and professional experiences. Such programming can help underserved students to realize that there is a place for them at law school and that the institution values and is invested in promoting diversity within its student body.

Ensure that law school environments are inclusive and welcoming

Once in law school, students may experience an unwelcoming environment that can at times be downright hostile. In particular, students from traditionally underrepresented communities have reported being harassed and discriminated against, which can negatively affect their academic performance and grades.108 For example, in 2018 and 2019, Black and female students at Harvard Law School received a series of degrading email and text messages from fellow students, which included “racist taunts about affirmative action and intelligence” and “body-shaming.” The students who received the disturbing messages explained how this mistreatment affected their studies: “It was all we could think about … all we could talk about, all we were focusing on, instead of our schoolwork.”109 Nonwhite students have also reported difficulty finding and joining study groups—particularly with their white peers—and feelings of isolation.110 Study groups can provide critical assistance in preparing for and excelling on law school exams.

In addition, students of color may find it disheartening to be taught by white professors who, in their teaching, fail to consider or outright dismiss the important nuances and unique experiences of communities of color. This is especially problematic when 82 percent of all tenured faculty and 80 percent of all full-time faculty members at U.S. law schools are white.111 Similarly, female students are often subjected to legal teachings that are colored by male-dominated perspectives. Women only comprise roughly 40 percent of full-time school faculty, while women of color comprise only about 9 percent of such faculty members.112 Moreover, LGBTQ students may be discouraged or feel overlooked if they are unable to self-identify on official law school forms and paperwork and do not see themselves represented among law school faculty.113

Finally, many law students of color and students from less affluent backgrounds do not enter school on a level playing ground with their white and elite counterparts due to structural barriers. And unfortunately, law schools do not always do a good job addressing the problem. Indeed, at many schools, there are few programs—outside of those organized by affinity law school clubs and bar associations—directed toward students of underrepresented groups or geared toward ensuring their success at law school and in the legal profession upon graduation.

One way to help these students feel a greater sense of belonging is for law schools to prioritize hiring faculty from a variety of backgrounds. Having a more diverse faculty can make law school feel more welcoming and inviting for students from historically underrepresented backgrounds, which can improve their overall experience. Moreover, having a diverse faculty—like a diverse group of judges—brings different perspectives to the classroom, which makes for a more comprehensive and well-rounded analysis of legal doctrine. Such robust discussions force students to recognize their own internal biases as well as the structural biases present in the legal system, helping to make them into better lawyers and judges.

Law schools should also set up special programming targeted toward female students, students of color, LGBTQ students, students with disabilities, and students from low-income backgrounds. Students from historically underrepresented groups such as these often face unique barriers navigating the law school experience, from applying and interviewing for jobs or clerkships to finding outside scholarships or funding for unpaid professional opportunities. In determining what programming is most helpful, law schools can conduct equity audits such as those described in CAP’s “Equity Audits: A Tool for Campus Improvement.”114 Equity audits can assist school administrators in making smart decisions about internal changes or improvements that must be made in order to empower students from different backgrounds to succeed.

Finally, law schools should hold events headlined by female judges as well as judges of different ages, races and ethnicities, socio-economic status, and any number of additional characteristics to talk about their experiences and encourage law students from all walks of life to follow similar paths.

Ensure that law students have equal access to professional opportunities

The many challenges that underrepresented students face in law school can prevent them from obtaining prestigious judicial clerkships and positions at distinguished law firms, both of which have traditionally been considered necessary for becoming a federal judge.

Many law students obtain highly sought-after clerkships through recommendations by the law professors who mentor them. But students belonging to historically underrepresented groups may find greater difficulty obtaining mentors among law school faculty. Although white, cis, and male law professors can be good mentors, students who do not fall into those groups may not seek out mentorships if they share little in common with their available potential mentors or suspect them of harboring prejudices. Aside from helping students obtain clerkships, mentors with shared characteristics and experiences can create safe spaces for students to go and report discrimination or harassment and seek advice in navigating a legal profession that is not friendly to lawyers from all backgrounds. With this in mind, law schools should create structured mentorship programs, whereby students interested in clerking can be paired with law professors from similar backgrounds to help them navigate the process.

An additional barrier for students wishing to obtain clerkships is that clerks are often only provided a small stipend for rent and other living expenses. Some clerks are also required to move temporarily depending on where their judge and court is located. For clerks who are financially secure or have a financial safety net to supplement their stipends, this is not a problem. But for others, such financial burdens can deter them from accepting clerkship positions. Indeed, students who lack the means to support themselves or supplement the limited stipends that clerkships offer may have no choice but to pass up such valuable opportunities, which could detrimentally affect their chances of obtaining a future judgeship.

To make clerkships more financially feasible, law schools should provide robust funding and scholarships to help students pursue unpaid or low-paying clerkship positions. Providing support for students from underrepresented communities pursuing clerkships helps both the student and the school, as getting more students placed in clerkships can improve the school’s ranking in post-graduate employment and attract more students who may be interested in clerking.

Like clerkships—and as noted previously—working at prestigious law firms is often considered an important step to becoming a federal judge. Accordingly, law schools should help students from all backgrounds secure these sought-after positions. Each fall, law schools across the country host events where law firms come to interview students for hiring opportunities. However, to promote inclusive hiring practices, law schools could allow only those law firms with proven records of hiring and retaining attorneys from historically underrepresented groups and diverse backgrounds to interview students at their school. Alternatively, law schools could give those firms special priority in selecting students to interview and hire. By only allowing law firms that foster and maintain diversity to participate—or by giving those firms priority—on hiring days, law schools can help incentivize other firms to improve diversity within their ranks. As an added bonus, law students who do get hired are more likely to be placed at a firm where they will be empowered to succeed.

At the very least, law schools should make information about law firm diversity statistics readily available to students and, on law firm interview and hiring days, provide students with rankings of firms based on their commitment to diverse hiring and retention.

Prioritize diversity in legal sectors that serve as stepping stones for judgeships

As described in previous sections of this report, working in certain sectors of the legal field—for example, serving as a judicial clerk, working at a top law firm, presiding as a state or local judge, or serving as a state attorney general or U.S. attorney—increases one’s likelihood of becoming a federal judge.

Unfortunately, people of color, women, and individuals from other underrepresented groups are less likely to be employed in these positions. Judges, law firms, politicians, and even voters have a role to play in helping to diversify these legal sectors. Steps must be taken to ensure that law students and lawyers from all backgrounds have access to these kinds of positions and that they are treated fairly once they attain them.

Judicial clerkships

Clerkship positions are not often filled by candidates from historically underrepresented groups. Previous sections of this report examined the lack of demographic diversity and variance in educational backgrounds among federal judges. But many of those same patterns hold true for federal law clerks.

Indeed, according to a comprehensive 2017 study compiled by researchers associated with Yale Law School and the National Asian Pacific ABA, as of 2015, 82.5 percent of federal law clerks were white.115 Meanwhile, Asians and Hispanics comprised approximately 6.5 percent and 4 percent of federal clerks, respectively, with Blacks making up roughly 5 percent.116 One reason for the lack of diversity among clerks is that federal judges place too high a premium on hiring clerks from elite law schools, and as noted earlier, a number of structural barriers can prevent students from underserved communities from enrolling at such institutions. The late Justice Antoni Scalia articulated judges’ preference for elite law students: “By and large, I’m going to be picking from the law schools that basically are the hardest to get into. They admit the best and the brightest, and they may not teach very well, but you can’t make a sow’s ear out of a silk purse.”117

Research shows that from 1950 to 2014, Harvard students accounted for nearly a quarter of all Supreme Court law clerks, with students from Yale comprising another 19 percent. During the same span, just 10 law schools combined accounted for nearly 82 percent of all Supreme Court clerks.118 And of law clerks who served on the lower federal courts from 2010 to 2014, more than one-third came from one of only 10 top schools—Harvard University; Yale University; Stanford University; University of Virginia; New York University; University of Michigan; University of Texas; Columbia University; University of California, Berkeley; and Duke University.119

Even when individuals belonging to historically underrepresented groups are selected for clerkships, they may feel isolated due to the lack of other clerks and judges with similar backgrounds. Some female clerks have even reported being sexually harassed by male judges.120

In hiring for clerkships, judges must look beyond law students and graduates who attended elite law schools and consider hiring clerks with different educational backgrounds and experiences. The elitist structure currently in place closes the door to many highly qualified individuals who would serve as exceptional clerks. Judge Vince Chhabria of the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California has suggested that judges adopt a practice similar to the NFL’s Rooney Rule, whereby judges would be required to interview at least one candidate from a demographically underrepresented group and at least one candidate from a law school not ranked in the top 14 for clerkship positions.121 According to Judge Chhabria:

Obviously, I don’t always hire law clerk candidates who meet this description. But interviewing off-the-radar candidates has sometimes led me to hire a fantastic person who might not originally have been given an interview. Other times I’ve not hired the person, but the interview with me has led to interviews with other judges (often on my recommendation). Overall, my hiring process has been better because of this practice, and it has resulted in stronger chambers.

Once they are hired, clerks must also have access to resources to report discriminatory or harassing behavior. Because clerks’ judges have immense influence on the trajectory of their careers, anonymous tip lines should be established for reporting abusive behavior by federal judges. Voluntary mentorship programs could also be established to pair clerks with former clerks from similar backgrounds. Such programs could help judicial clerks of all backgrounds to navigate the judicial institution.

Law firms

Like clerkships, prestigious law firms are also highly selective and favor law graduates who attended elite law schools and graduated at the top of their class. But again, as explored in previous sections, the many obstacles that students from traditionally underserved communities face in law school may cause their GPAs to suffer, especially in comparison with their elite peers, who are advantaged by the current system in many ways.

According to a report by the National Association for Law Placement, in 2018, Asians made up 11.69 percent of associates at U.S. law firms, while Hispanic and Black/African American associates comprised 4.71 percent and 4.48 percent, respectively.122 Moreover, only 0.46 percent of associates reported having a disability and 3.80 percent identified as LGBTQ. According to the same study, women comprised slightly less than half of law firm associates that year.123 Diversity is worse among law firm partners. The same study found that only 1.83 percent of law firm partners in 2018 were Black or African American, while 2.49 percent were Hispanic. And women of color comprised just 3.19 percent of law firm partners at U.S. law firms in 2018.124 Fewer than 1 percent of law firm partners reported having a disability, while slightly more than 2 percent identified as LGBTQ.125

Candidates from underrepresented backgrounds who do get hired at law firms are not always primed for success. Women, people of color, and LGBTQ people have reported being discriminated against, harassed, or passed over for promotions and assignments at law firms. According to an ABA study, 49 percent of women of color working at law firms have reported being subject to harassment, while 62 percent reported being excluded from networking opportunities critical for career advancement. In comparison, between 2 and 4 percent of white men working at law firms reported experiencing the same issues.126 The study also found that women of color were significantly more likely to report receiving unfair performance evaluations than their white male peers. Additionally, law firm associates who identify as LGBTQ have reported regularly hearing anti-gay comments in the workplace.127 In regard to the distribution of clients and assignments, some advocates have noted an apparent favoritism within law firms toward “gay male lawyers who are very masculine and lesbian women who are more feminine” over other associates who identify as LGBTQ.128

When individuals feel unsupported or even attacked in the workplace, they are more likely to leave their prestigious positions or the law profession altogether. Studies have shown that lawyers of color are more likely to leave their firm jobs than white lawyers.129 A 2007–2008 report by the ABA noted that women of color, in particular, have a nearly 100 percent attrition rate from law firms after just eight years.130 This, in turn, shrinks the pool of possible judicial candidates from certain historically underrepresented groups.

Like judges and clerkships, law firms must make hiring decisions with an eye toward bringing on more women, people of color, people who identify as LGBTQ, and people with disabilities as well as different religious affiliations. Hiring decisions can be facilitated by in-house diversity committees comprised of associates, partners, and staff from a variety of backgrounds who can monitor the firm’s hiring practices to ensure that candidates are being fairly considered and that the firm’s diversity goals are being met. Fortunately, many law firms have implemented the Mansfield Rule, which requires at least 30 percent of firm leadership candidates to be members of historically underrepresented groups.131 Some law firms have even started conducting diversity seminars for firm attorneys and their clients in order to increase knowledge about diversity issues and the unique challenges faced by individuals from underrepresented groups.132 To be effective, diversity committees within firms must have teeth. They must be empowered to make independent assessments of and take meaningful action to address problems within firms related to diverse hiring and retention practices, as well as to ensure that workplace conduct and work distribution are free of discrimination and harassment.

Clients are also prioritizing firm diversity. For instance, a number of businesses seeking outside counsel are committed to hiring law firms with lawyers from historically underrepresented groups, such as firms endorsed by the National Association of Minority & Women Owned Law Firms (NAMWOLF).133 Client-led diversity initiatives help to empower diversity-minded law firms in a highly competitive legal field and to provide strong incentives for other firms to diversify their ranks and take concrete steps to retain attorneys from historically underrepresented groups.

It is also important to improve firm culture in order to increase retention rates among associates and partners from historically underrepresented groups. Safe workplace and bias trainings must occur regularly, and individuals who make bigoted or offensive comments must face repercussions, regardless of their place on the hierarchical totem pole. There must also be formal processes for investigating performance evaluations and work distribution patterns that may be tainted by supervisor bias. Firm attorneys belonging to historically underrepresented groups should be paired with mentors who are invested in their success. These mentors may themselves be members of underrepresented groups, but they may also be senior associates and partners that are not from such groups. In fact, some lawyers of color have acknowledged that being paired with white partners can be crucial for their success, given that they may have more connections with others in the legal field or larger client lists.134

State supreme courts, attorneys general, and U.S. attorneys

Aside from clerkships and jobs at prestigious law firms, federal judges are also recruited from state supreme courts and attorneys general (AG) offices. Unfortunately, diversity is a problem in these areas as well.

A recent report by the Brennan Center for Justice found that judges of color comprise just 15 percent of state supreme court seats nationwide. Nearly half of all states have supreme courts comprised entirely of white judges.135 Meanwhile, female judges comprise just 36 percent of state supreme court seats. The same diversity issues exist for attorneys general. In fact, there are only nine women and 12 people of color currently serving as state attorneys general, comprising only about 17.6 percent and 23.5 percent, respectively, of all state attorneys general nationwide, including Washington, D.C.136 Moreover, of assistant U.S. attorneys in 2013 and 2014, the vast majority, nearly 81 percent, were white; only 5.2 percent were Asian, 8 percent were Black, and 5.2 percent were Hispanic.137

Addressing diversity problems in these sectors requires diversity-centered decision-making by governors, presidents, and the public, who appoints or elects state supreme court judges and attorneys general.

Prioritizing judicial diversity in the nomination and appointment process

Addressing the pipeline problem, as explored above, will go a long way toward ensuring that there is a larger pool of judicial candidates from which to choose for the federal bench. But ensuring that future judicial candidates are set up for success in and out of law school is only half the battle. Even if lawyers from different backgrounds play their cards right under the current system—by going to the most prestigious law school, graduating at the top of their class, clerking at the Supreme Court, and then making partner at a top law firm or presiding over a state supreme court—they still face an uphill battle in attaining a federal judgeship.

As explored in Part I of this report, despite their exceptional qualifications, judicial candidates from underrepresented groups are far outnumbered by cis white male judges on the federal courts. Solutions are therefore needed to ensure that candidates from all backgrounds are being nominated by presidential administrations and approved by Congress.

The White House and Congress must place a premium on judicial diversity

As illustrated in previous sections of this report, for much of American history, U.S. presidents have failed to prioritize diversifying the federal bench. Except for during the administrations of former Presidents Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama, judicial nominations of people from underrepresented groups have been few and far between. Similarly, even when candidates of color, women, and openly LGBTQ candidates have been nominated, Congress has been slow to confirm their appointments.

Why hasn’t judicial diversity been a priority for most presidents and Congress?

Some politicians may argue that when it comes to the federal judiciary, it is unnecessary to add more women, people of color, individuals self-identifying as LGBTQ, people with disabilities, and those belonging to minority religions because in applying the “black letter” law, judges render decisions objectively and free of bias.138 But this argument is flawed, as demonstrated in earlier sections of this report. Another explanation is that in nominating and confirming federal judges, presidential administrations and Congress must make various considerations and strategic calculations. Depending on the political climate at the time, judicial diversity may unfortunately fall by the wayside even under administrations with the best intentions. Finally, one cannot discount politicians’ personally held biases and prejudices toward certain historically underrepresented groups. Such biases have undoubtedly played a significant role in the disproportionately small percentage of judges from underrepresented groups who have been nominated and appointed to the federal bench since the nation’s founding.

In nominating judges, presidents must make diversifying the bench a top priority for their administrations. As discussed previously, President Carter was a leader in this area. When he signed the Omnibus Judgeship Act of 1978—which, among other things, added new judgeships to the federal courts—Carter recognized his duty to address “the almost complete absence of women or members of minority groups” on the federal bench.139 In doing so, he reportedly ignored white senators who recommended only white judges for the bench, issuing a series of executive orders aimed at improving diversity among federal judges. Professor Nancy Scherer described Carter’s efforts in her article “Diversifying the Federal Bench”:

First, Carter set out to dismantle the traditional method of selecting lower court judges—senatorial courtesy—which had perpetuated the old white boys’ network. Second, Carter directed the appellate merit selection committees to make ‘special efforts’ to identify minorities and women for appellate vacancies. Third, Carter directed his Attorney General to make ‘an affirmative effort … to identify qualified candidates, including women and members of minority groups’ for federal judgeships.140

President Obama, too, consciously selected judges who represented a variety of backgrounds and experiences. In a 2007 campaign speech, he maintained: “We need somebody [on the bench] who’s got the heart—the empathy—to recognize what it’s like to be a young teenage mom. The empathy to understand what it’s like to be poor or African-American or gay or disabled or old—and that’s the criteria by which I’ll be selecting my judges.”141

Presidents must emulate the examples set by Carter and Obama to diversify federal courts. Efforts to diversify the federal bench cannot, however, be limited to demographic characteristics. In addition to compiling a group of nominees from different racial and ethnic backgrounds, genders, LGBTQ identities, and religious affiliations, presidents should nominate judges who come from different educational and professional backgrounds. That the federal judiciary is made up largely of judges who worked in private practice and as prosecutors is problematic since it means that a very small subset of perspectives dominate the judicial system. There are many lawyers who would make excellent judges that are currently working in the public sector, including as public defenders, nonprofit litigators, and as direct legal service providers. Although such career paths have historically not been pathways to federal judgeships, they certainly should be.

It is worth recognizing that despite the Obama administration’s efforts to diversify the federal judiciary, women and people of color still comprised fewer than 50 percent and 40 percent of his appointees, respectively. LGBTQ judicial appointees were similarly underrepresented compared with their share of the U.S. population. That Obama—who arguably did more to improve representation on the federal bench than any other president—did not appoint people from historically underrepresented groups at rates of even 50 percent is noteworthy. In order to make any real dent in the diversity problem that plagues the current judiciary, the proportion of women and people of color being appointed needs to be much higher, greatly exceeding any 50 percent threshold. LGBTQ judges, judges with disabilities, and judges belonging to religious minorities should also be appointed at significantly higher rates.142 And as discussed earlier, a large proportion of judicial appointees should also come from different professional backgrounds and educational experiences.

In nominating and confirming judicial appointees, presidential administrations should engage in robust consultation with a variety of groups and communities. Affinity organizations and bar associations, disability rights and justice advocates, and interfaith coalitions and leaders specializing in judicial nominations can provide a wealth of valuable insight on and recommendations for judicial nominees from different backgrounds and experiences.

Like the executive branch, the legislative branch must also make confirming these nominees a matter of utmost importance. The Senate should demand nominees who belong to underrepresented groups and who come from different backgrounds. It should no longer be a complacent party in confirming more and more white, male, and elitist judges. The Senate has significant power over the judicial confirmation process and, as such, should be more assertive in pushing for greater diversity on the bench. Senators should similarly consult with justice-oriented groups and affinity bar associations when confirming judicial nominees. Such organizations can warn lawmakers about nominees with poor records on issues that disproportionately affect historically underrepresented groups.

Addressing inequities in the ABA’s judicial rating system

Although the ABA does not exercise any formal authority over who gets nominated or appointed to the federal bench, it plays an influential role through issuing ratings on federal judicial nominees. The ABA’s rating system, which was explored in CAP’s “Structural Reforms to the Federal Judiciary,” considers a nominee’s integrity, professional competence, and judicial temperament, and has been relied upon by presidents and senators for the past several decades. Unfortunately, research suggests that the ABA rating system disproportionately disadvantages judges belonging to historically underrepresented groups. For instance, female judges and judges belonging to racial or ethnic minorities are less likely than their male and white counterparts to be highly rated by the ABA, even though there is zero evidence that white or male judges are more qualified than those belonging to underrepresented groups.143 This is a serious cause for concern and requires immediate remedy.

Require judges and court staff to regularly undergo implicit bias training

The recommendations listed above are steps that can be taken to ensure that, going forward, judicial vacancies are filled by judges who belong to historically underrepresented groups and have a variety of experiences. There, of course, remains the question of what to do about the judges already serving on the federal bench.

As described in previous sections of this report, judges—like everyone else—have implicit biases regarding race, gender, sexual orientation, religion, and so on. Although it is impossible to eliminate judicial bias in its entirety, steps can be taken to mitigate its effect.

For example, federal judges—including Supreme Court justices—along with all senior court employees and law clerks, should be required to undergo implicit bias training on an annual basis.144 Such training could cycle between focusing on various biases, including those having to do with gender, race, sexual orientation, socio-economic status, religion, and people with limited English proficiency or disabilities. Trainings could be carried out by implicit bias specialists and include presentations from affected litigants as well as organizations and bar associations representing various groups and communities, specifically those that are historically underrepresented. Implicit bias training could be mandated by the Federal Judicial Center or required by Congress. All federal judges are already required by law to complete annual financial disclosures in the interests of transparency and accountability.

Another way to mitigate bias is for state bars to require trainings as part of their Continuing Legal Education curriculum, as is the case in Minnesota.145 Nonprofit groups can also get involved by monitoring court practices to identify judicial bias in the courtroom. For instance, organizations engaged in court monitoring practices will often send trained volunteers to monitor certain classes of court cases for judicial bias against parties and attorneys. These organizations can then provide feedback to judges on their performances and offer judicial bias trainings to address the problem.146 Programs can be designed to monitor judicial bias as it pertains to different historically underrepresented groups.