Every time a dangerous wildfire breaks out somewhere in California, fire crews race to battle it. Incarcerated people play a major role in this effort; the state has about 2,600 incarcerated people fighting wildfires under the state’s fire camp program. Over the past four years, the state has had trouble recruiting for this program. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection (Cal Fire) blame prison “population reduction strategies,” according to a document obtained by Earther through a public records request.

The state has made some slight changes in an attempt to entice more incarcerated people to participate in the Cal Fire program. The state used to pay the workers a meager $2 a day with an additional dollar an hour when the inmates were actively fighting a fire. Since March, incarcerated people performing firefighter duties have earned $5.12 a day as part of the state’s effort to attract more interest in the program, according to the CDCR. Cal Fire didn’t return Earther’s repeated requested for comment.

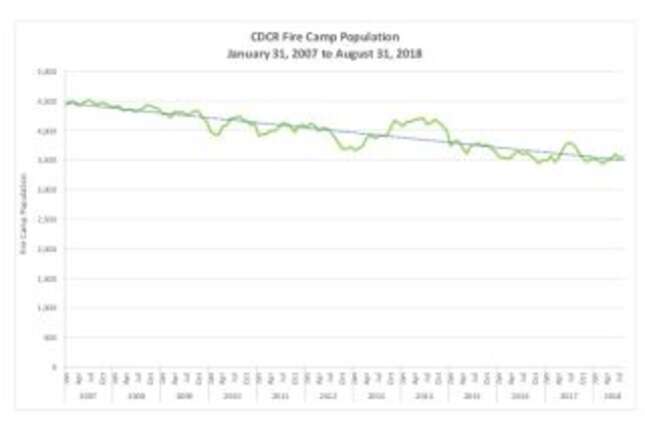

The gig pays better than other prison jobs. Although $5 an hour is paltry pay for any work, most other prison jobs in California barely pay a dollar an hour, an unacceptable amount by any account, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. And participating in the firefighting program can result in reduced prison sentences. But despite these enticements, the fire camp population has dropped by nearly 1,000 since 2007 to about 3,700 in 2018, which includes those who work at fire camp and perform non-firefighting duties, according to state data Earther received from public records requests.

Since at least 2015, CDCR and Cal Fire began sounding the alarm internally about this shortage of prison labor. Cal Fire and CDCR lay the blame on prison reform, according to an information sheet released in September 2015 Earther obtained through a California public records request. After 2011, the prison population eligible to join fire camps began to drop due to Assembly Bill 109, which worked to address overpopulation in state prisons. Then in 2014, came Proposition 47, which reclassified some drug and theft offenses from felonies to misdemeanors, further reducing the number of people in prison.

Under the leadership of Kamala Harris—then California’s attorney general and now Democratic presidential candidate—the attorney general’s office even fought to stop these reforms in order to keep the fire camp program alive. Her office repeatedly intervened in a Supreme Court case that pushed California to reduce its prison populations. On September 2014, the office filed a court motion opposing a motion that would expand two-for-one time credits—which give incarcerated people two days off their sentence for every one day served—to all incarcerated people with minimum-custody classification, the populations that require the least supervision due in part to good behavior, in California prisons, not just fire camp workers.

Harris’ office wrote in the motion:

Extending 2-for-1 credits to all minimum custody inmates at this time would severely impact fire camp participation—a dangerous outcome while California is in the middle of a difficult fire season and severe drought. ...

The extension of 2-for-1 credits to all [minimum security facility] inmates would likely make fire camp beds even more difficult to fill, as low-level, non-violent inmates would choose to participate in the MSF program rather than endure strenuous physical activities and risk injury in fire camps.

Fighting wildfires isn’t easy work, especially as California’s wildfires grow more extreme in a warming, drying climate. There’s a risk of severe burns, which happened to five incarcerated people while battling the deadly Camp Fire last year. There’s also respiratory risk from breathing all the smoke. Fire season is becoming a year-round occurrence as our climate changes. Add low wages into the mix, and it makes sense why the interest in the program has waned over time.

“It might be that, frankly, the pay is so low, the work is so hard and dangerous, that it could be that people say, ‘This is just too much, too dangerous and difficult and risky kind of work,’” Marc Morjé Howard, the director of Georgetown University’s Prisons and Justice Initiative, told Earther.

Fire season has been quiet so far this year, but last year’s blazes were enough to last a lifetime. It was the state’s “deadliest and most destructive” season on record, per Cal Fire. Nearly 1.7 million acres burned across the state, and incarcerated individuals helped put many of the fires out.

While the state could hire firefighters that aren’t behind bars to take on this gargantuan task, California saves some $100 million a year by relying on prison labor. Instead of hiring more professional firefighters, Cal Fire and CDCR proposed increasing the hourly wage of incarcerated firefighters by a dollar since 2015, according to five internal memos Earther reviewed.

That raise would cost the state an extra $200,000 a year, so it opted for a different kind of raise after years of this same proposal being rejected: increase the amount of money incarcerated firefighters would receive per day. The raise to $5.12 a day more than doubles the daily rate of this work, but CDCR wouldn’t disclose to Earther whether the raise has been successful in increasing the number of people joining the program. It also wouldn’t elaborate on why it chose the daily raise rather than the hourly one.

Increasing the number of fire camp participants is ultimately the goal, as these documents make clear. The state really depends on this workforce to help prevent wildfires from burning out of control. Incarcerated people are stationed in special camps near where fires tend to break out. They have more privileges than your average prisoner, including the ability to walk around, access the outdoors, and even better meals, some incarcerated people have told Earther.

Still, what they earn is next to nothing compared to what they would earn if the state actually employed them. Entry-level firefighters with Cal Fire can make up to nearly $14 an hour, according to the Sacramento Bee. After overtime pay, however, some higher-ranking employees, including fire captains and chiefs, earned more than $200,000 last year. The pay gap is serious.

“I’m not completely opposed to labor in prison,” Howard told Earther. “I think, actually, it’s a very effective way of socializing people, of getting them used to a routine, of preparing them for the labor force. There are all kinds of positives that come from prison labor—I just think that there should be fair compensation for work people are doing. ”

This raise does show some progress, Nicole Porter, the director of advocacy at the Sentencing Project, told Earther, but the wages are “extremely modest” given the risk incarcerated firefighters face in their line of work. She’d rather a system that allows workers to unionize and set the terms of their work and compensation.

Battling wildfires is an especially tough situation for Howard to break down, though. Many of the incarcerated people fighting fires have great pride in their work. Howard called their duties “heroic.” Lives, homes, and entire towns are sometimes at stake when wildfires flare up. But so are the lives of those working to protect others. And some might argue that if these individuals are deemed “safe” enough to perform life-saving labor outside the prison walls, why are they incarcerated at all?

“Incarcerated workers are doing labor for very low wages,” Porter said. “Those are valid concerns, but what’s also valid is the waste of humanity that’s disappeared behind prison walls for very excessive sentences and the reliance of this country on incarceration to begin with.”

To make matters worse, these individuals can rarely land a job in fighting fires once they’re released. The space is competitive, and a criminal record can harm a person’s chances. So the daily raise to $5.12 is great, but access to employment once these incarcerated people are free is essential too, advocates argue.

CDCR noted that it offers all its incarcerated people in their program training at the Ventura Training Center after they finish their sentences, but it’s unclear how much that improves someone’s chance of landing a job as a firefighter. Last year, the state finally passed a bill that allows Cal Fire to certify some incarcerated people as emergency medical technicians, which many weren’t able to do so previously with a criminal record, to make obtaining jobs a little less difficult.

But much work remains, and California’s fire season is about to kick into high gear with the National Interagency Fire Center forecasting an increased risk of “significant” fires through November.

Michael Waters contributed reporting to this story.

If you have any information about California’s fire camps and the state of inmate labor you’d like to share with Gizmodo, email yessenia.funes@earther.com.