The Media Barely Covered One of the Worst Storms to Hit U.S. Soil

Weeks ago, Super Typhoon Yutu devastated the Northern Mariana Islands, which are home to tens of thousands of Americans. Mainland outlets paid little attention.

Several hours before Super Typhoon Yutu struck the morning of October 25, Harry Blanco was making final preparations for the storm. He boarded up the windows of his house, secured loose objects outside, gathered his valuables in a backpack, and locked his black Labrador, Lady, in the laundry room, where he felt she’d be safe. Then, he—along with thousands of his neighbors in the Northern Mariana Islands—waited in their homes. The remote American territory in the western Pacific would soon face the biggest storm to hit U.S. soil since 1935.

As night fell, Yutu swept toward Blanco’s village on the island of Saipan. The howling outside intensified, and Blanco’s partially wooden home began to buckle in the sustained 180-mph winds. “The house started shaking,” recalls Blanco, a 56-year-old retired U.S. Army colonel. “I started getting scared because it was not fully concrete.” But his bathroom was, so he retreated there. Just after midnight, the roof that covered half of his house was ripped off, and Blanco felt the furious winds trying to suck him up into the air. “I jumped in the bathtub,” he said. “I was holding myself down using the spout ... It was wet, so it was slippery.”

Finally, there was a small break in the wind. Blanco ran to collect a shaking and crying Lady, dashed into a bedroom where the roof was still intact, and took cover under a three-foot desk. The pair crouched together in the dark as the room flooded and the winds screamed. Blanco braced himself for the rest of the roof to tear off. But it held. “We hung in there for the entire typhoon,” he said. “It was close to eight and a half or nine hours, but at least we were safe.”

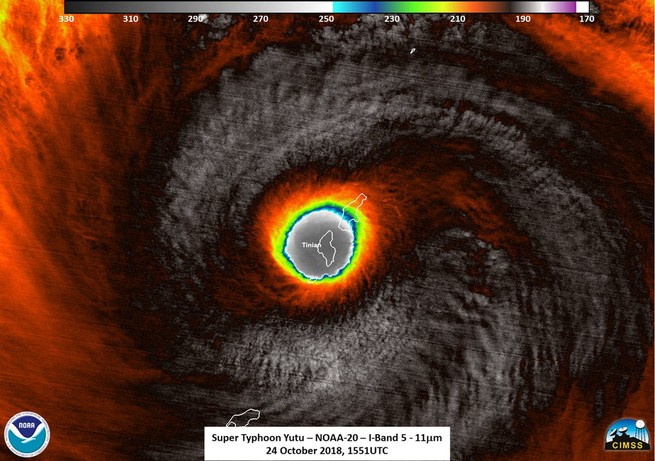

Blanco was one of more than 50,000 people living in the U.S. Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands when Yutu hit. Typhoons are a fact of life in the region—so much so that people commonly judge a storm’s strength by whether the banana trees are still standing afterward. Many residents had only just finished recovering from Super Typhoon Soudelor, which hit three years ago. Yutu, according to Blanco and others, was even more monstrous. The eye of the cyclone alone engulfed the entire island of Tinian and the southern part of Saipan at once. The two islands, along with Rota, are the major population centers in the CNMI.

Two people were killed, hundreds were injured, and more than 3,000 houses were destroyed, leaving thousands homeless. Much of Saipan and Tinian is expected to go without power for months, and severe water shortages remain—an especially dangerous situation given the intense heat and humidity in the tropical islands. The vital work of debris-clearing continues for an area that several residents, including military veterans, have likened to a battlefield: Massive power lines lie strewn across roads. Metal roofs curl around poles like bits of foil. Homes in village after village have been reduced to rubble. Damage to local airports and logistical decisions that prioritize inbound recovery workers have choked off tourism, which drives the economy here. Elections were postponed to make way for highly coordinated relief efforts from the CNMI government, FEMA, the American Red Cross, the Department of Defense, and local charities.

Despite the tens of thousands of American citizens affected, mainstream-U.S. media coverage of Yutu has been woefully limited. This reality is at once disappointing and expected for those living in the CNMI and on the nearby island of Guam. Together, the two U.S. territories make up the Mariana Islands—an archipelago about a three-hour flight from Japan and at least 13 hours from California. Home to the indigenous Chamorro people as well as many other Asian and Pacific Islander ethnic groups, the Marianas can seem like an abstraction to those in the continental U.S. Many Americans know these islands either as distant sites hosting major U.S. military bases (as highlighted by North Korea’s nuclear threat to Guam last year), or as postcard-perfect tropical paradises.

National coverage of Yutu—from outlets including The New York Times, CNN, the Los Angeles Times, The Wall Street Journal, and ABC News—was largely limited to republished stories from wire services such as the Associated Press and Reuters. Many of these papers or networks had few or no original stories about the typhoon and its aftermath. (This is The Atlantic’s first story about Yutu.) A three-person team from The Washington Post wrote a couple of longer, deeply reported Yutu pieces, and the paper also ran multiple weather-related articles. But when the typhoon was covered, stories tended to be cursory or focused more on Yutu’s meteorological significance. Considerably less attention has been paid to the realities of recovery for typhoon victims, who will be rebuilding for years to come.

After the typhoon, some media critics called out the industry’s failure to adequately cover Yutu, while acknowledging that it happened the same week that a shooter killed 11 at a Pittsburgh synagogue and pipe bombs were sent to high-profile Democratic figures. The HuffPost reporter Chris D’Angelo noted that the silence about Yutu echoes the meager coverage another U.S. territory, Puerto Rico, initially received when Hurricane Maria struck last year, killing nearly 3,000 people. D’Angelo pointed out that President Donald Trump, despite having tweeted about other natural disasters in the U.S., posted nothing about Yutu. Though Trump signed emergency and disaster declarations freeing up federal aid for the region, CNMI residents we spoke with remarked on his silence about the typhoon.

Anita Hofschneider, a Honolulu-based reporter from Saipan, wrote for Columbia Journalism Review about the dearth of Yutu stories, speaking with people living in the Marianas and tracking the extent of media coverage. In a recent piece on the ethics of attention, our colleague Megan Garber mentioned Yutu as one of many crucial events that Americans may be overlooking, given the relentless news cycle.

In the days after Yutu, many people on Saipan and Tinian were too busy thinking about food, water, medical care, and housing to engage in much media criticism. G. Van Gils, the executive director of the educational nonprofit Marianas Young Professionals, has been leading a massive grassroots relief effort in Saipan. Not long after Yutu, he watched as a row of homes that had survived the storm caught fire; there wasn’t enough water on hand to put out the blaze. “A single mother with three children under the age of 10 watched every single possession burn one week after a typhoon,” Van Gils said. Afterward, he brought the family to a temporary shelter, where two of the children drew a picture of their home. “Before …,” they wrote, over an image of a house covered in smoke and fire. “After …,” they wrote, over some black scribbles. “No more house.”

Joey P. San Nicolas, the mayor of Tinian, said in an email that he doesn’t have much of an opinion on how mainstream news media covered Yutu; these institutions, he added, rarely cover the region to begin with, despite its importance to U.S. trade and national security. “I do know that media outlets in Hawaii, Guam, and Saipan provided accurate and extensive media coverage on Super Typhoon Yutu,” said San Nicolas, who has been preoccupied with rebuilding the island. Tinian restored 100 percent of its water production earlier this week.

Saipan Mayor David M. Apatang echoed some of San Nicolas’s sentiments. “National media coverage is not too high on the priority list of the people that live in the Mariana Islands after a devastating typhoon,” he said in a statement. “Although it is still necessary to have the exposure, the immediate need is assistance to help everyone get back on their feet again.” Unfortunately, he noted, the lack of coverage meant the family members of people in Saipan and Tinian living elsewhere had to rely heavily on social media to fill in the gaps.

Many people with ties to the CNMI living in the continental U.S. have turned to their local media outlets for help. “Everyone! Let’s call our local radio stations and see if they’ll help us spread awareness about what’s happening back home,” a Boise-based woman from Saipan named Shella Johnson wrote in one Yutu-recovery Facebook group with more than 1,000 members. Some attempts to garner attention were successful, with a smattering of local pieces publicizing relief efforts in the area. But Johnson said she contacted five Christian or news radio stations, most of them based out of Idaho, to try to promote donation drives in the area, and as of Tuesday had heard back from only one outlet.

Johnson’s story appears to be part of a broader pattern. We spoke with eight Yutu relief volunteers in the continental U.S., most of them based in or around Pacific Islander enclaves in California, Idaho, and Oregon. Each reported failing to get local news coverage. Manny Tenorio, a Saipan native in Salem, Oregon, emailed a TV station in Portland saying that Yutu survivors needed urgent supplies such as water, nonperishable food, and blankets. Tenorio received a response, but didn’t hear back after an initial exchange. Virtually every other advocate we spoke with who contacted their local news station told us they were met with crickets, despite sending several emails and emphasizing the gravity of the disaster. We reached out to all 12 outlets and received responses from three journalists, including one who said the issue was beyond the scope of her responsibilities and another who explained that his newspaper doesn’t cover “pop-up charities” that aren’t registered as official nonprofits.

Reflecting on the paucity of media attention, many advocates expressed anger and disillusionment, feelings exacerbated by news updates about ongoing struggles in the CNMI. Many survivors of natural disasters go on to face economic havoc, the spread of disease, and political dysfunction. Poorer communities—especially in the Asia-Pacific region—are especially vulnerable to natural disasters: Yutu went on to kill at least 25 people in the Philippines, where 127 people had died as a result of Typhoon Mangkhut only weeks earlier. In addition, the Pacific islands are increasingly threatened by rising sea levels, warming ocean temperatures, and other climate-related changes.

For some in the Marianas, things only got more dire after Yutu. Elena Relox, a 49-year-old Saipan resident originally from the Philippines, lost her apartment and everything inside of it to the same fire Van Gils witnessed. “It’s all gone,” Relox kept repeating in a phone conversation the following day. “Everything is gone.” When we spoke, Relox had just found temporary shelter at a hotel. All of her loved ones on Saipan—including her son, who was helping to lead recovery efforts on top of dealing with the loss of his home—were in triage mode. She struggled, however, when reminiscing about her destroyed photos, namely those of her now-adult children from when they were young. That her daughter is 3,700 miles away attending college in Honolulu made this new void even more painful.

The Pacific Ocean is just one of the many chasms between the continental U.S. and its territories in the Marianas; there are cultural, political, and economic rifts, too. Many people from the area move to the mainland “for college and then they have to figure out when are they are going to come back, and what does it mean to come back,” says Sophia Perez, a 25-year-old Chamorro who grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area but now lives on Saipan. The Chamorro diaspora throughout the continental U.S. and beyond is significant, partly because of the educational and professional opportunities available off-island, but also because of the territories’ famously high rates of U.S. military service.

Geography may be the simplest explanation for why even epic disasters like Yutu get overlooked. Essentially, the islands are so far away from the rest of the U.S., and so small, that they’re easy to forget. Even the language sometimes used to talk about these territories subtly frames them as unimportant. Tiara R. Na’puti, a Chamorro who is an assistant professor of communication at the University of Colorado at Boulder, said she doesn’t like using the term mainland, for example. “Mainland doesn’t make you think of these seemingly faraway, disparate islands where some people live, and that lack of attention really has devastating impacts,” Na’puti said. Mainland, she added, frames the continental U.S. as the center of discourse and everything else—particularly island territories—as peripheral. Which is to say that language matters because it helps translate hierarchies of geography into hierarchies of attention. Notably, some stories about Yutu don’t even mention that the CNMI is part of the U.S.

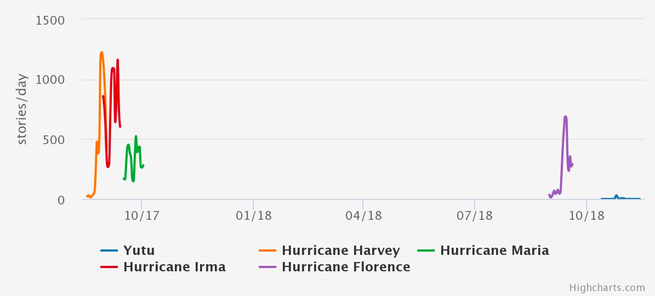

This erasure is compounded by limited political representation for citizens in U.S. territories (three of which are still considered colonies by the United Nations). Na’puti and others pointed to Puerto Rico, which accounts for the vast majority of the 4 million or so Americans living in territories with no voting representative in Congress. An analysis published by FiveThirtyEight demonstrated that the catastrophic Hurricane Maria garnered little media coverage relative to Harvey and Irma, which ravaged communities in the continental U.S. The piece cited Puerto Rico’s territory status, and a general ignorance of the fact that most of the island’s 3.4 million residents are American citizens, as potential key factors.

Race and class, too, may play a role in the Marianas’ relative invisibility in political and media arenas. People in the CNMI are predominantly Chamorro, Filipino, Chinese, Korean, Carolinian, Bangladeshi, and members of other ethnic groups that are often marginalized in the U.S. As of 2015, 51 percent of people in the CNMI were living below the poverty line, a figure that’s only exacerbated by traumas like Yutu. Keith Camacho, an associate professor of Asian American studies at UCLA, sees parallels between the CNMI and other impoverished groups across the U.S. “The way the United States treats the territories in the Caribbean and in the Pacific Islands is very much akin to how the U.S. government treats poor and working communities in Detroit, in the heartland, in the rank and file of white workers in the South, in poor communities in Los Angeles, in disenfranchised communities in Philadelphia,” he said.

People in Saipan and Tinian painted a vivid picture of the on-the-ground crisis. But nearly everyone was careful to also highlight the local culture of resilience. Marianas Young Professionals has mobilized an army of volunteers to deliver thousands of hot meals, distribute water door-to-door, house several families, and take care of people’s emotional and psychological needs. “People are moving all over the island seeking shelter,” Van Gils said. “That means their communities and strength networks have been displaced as well. They used to go ask their neighbor for a can of Spam and a cup of rice. Those neighbors are gone now, so who do they ask?” He said many of those leading relief efforts are young people who currently can’t go to work or school. By getting to run such a large-scale project, Van Gils said, they’re gaining valuable professional experience while also bolstering local institutional knowledge of typhoon relief.

While mainstream U.S. media have all but forgotten Yutu, local journalism has been robust: The Saipan Tribune—as well as the Pacific Daily News, Pacific News Center, Marianas Variety, and KUAM—has been covering the typhoon and its aftermath relentlessly. Mark Rabago, the associate editor of The Saipan Tribune, said that when Yutu arrived, he and his colleagues communicated using Facebook Messenger and posted updates about the storm to the Tribune website until the power went out early the next morning. Once the weather cleared, their work continued. “As reporters and editors, you’re supposed to be even-keeled when observing events,” Rabago said in an email. “But seeing former haunts and houses of friends turned into what looked like a war zone was overwhelming.” He said the Tribune went two days without a physical paper because the entire island had no power. Other local photographers, such as Leni Leon, have been documenting the experiences of people putting their lives back together.

Those from the Marianas living in the continental U.S. have long relied on workaround means of organizing and spreading information, with much of their approach built on indigenous cultural values. Roz Guerrero, a Chamorro from Saipan who lives in Vancouver, Washington, described this system as a “phone tree.” She and others throughout the mainland diaspora “activated” this tree as soon they learned of Yutu, spurring relief drives across the country. In the days since Yutu, Guerrero has been literally living according to “Saipan time,” which is 18 hours ahead of her time zone in the Pacific Northwest. Although she was infuriated by the lack of media coverage, her resentment was overshadowed by the “outpouring” of support from the local Pacific Islander community. “The one term I could use is [the Chamorro word] Inafa’maolek, and that means ‘to come together, to be together, to support each other,’” she said. “It doesn’t matter how far or how near we are.”