Guest Post by Juan Pacheco

Virginia Tech’s history is a complicated one that is much more presumed than known due to an early 20th century blaze. In its early years, the institution served as an allegory of the rough, rag-tag, Appalachian spirit we see still embodied through a beaten-up lunch pail at football games and the largely blue-collar valley that envelops us. Tech, unlike its sister institutions William and Mary and the University of Virginia, has never owned any enslaved people by circumstance of its post-antebellum founding in 1872. Even its predecessor institution, the Olin & Preston Institute, has no record of owning any. That is not to say, however, that the grand 2,600-acre Blacksburg campus has never met or benefited from the harsh legacy of slavery.

Prior to last year, you most likely would not see him listed on the Virginia Tech Black History Timeline. He predates Charles “Uncle Sporty” Owens, Floyd Meade, and even Odd Fellows Hall, all well-known black figures in early Virginia Tech history. If you had the privilege of crawling around the campus of Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College about 148 years ago with Addison Caldwell and other “rats,” you’d most likely refer to him as “Uncle Andrew.” He is Andrew Oliver, and he is the first known African-American worker at what is now Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

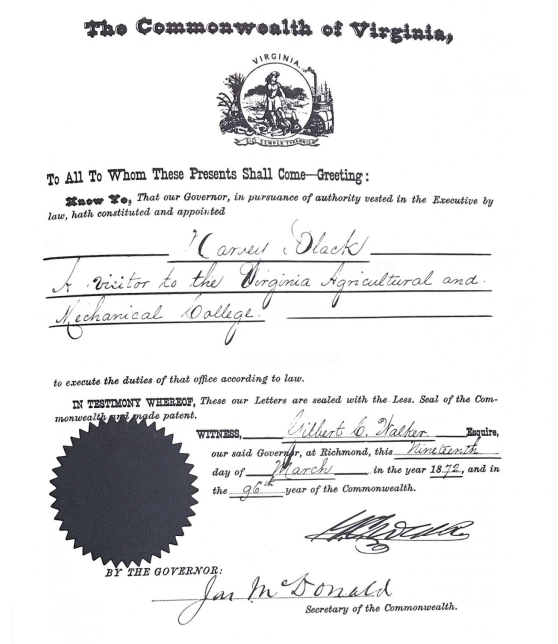

Andrew Oliver was born into enslavement in about 1837. The Black family (yep, the family for which our town is named) owned him. I would be remiss if it was not also emphasized that Harvey Black’s signature is on the oldest document connected to Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College; Harvey was appointed first rector of the Board of Visitors for the new institution.

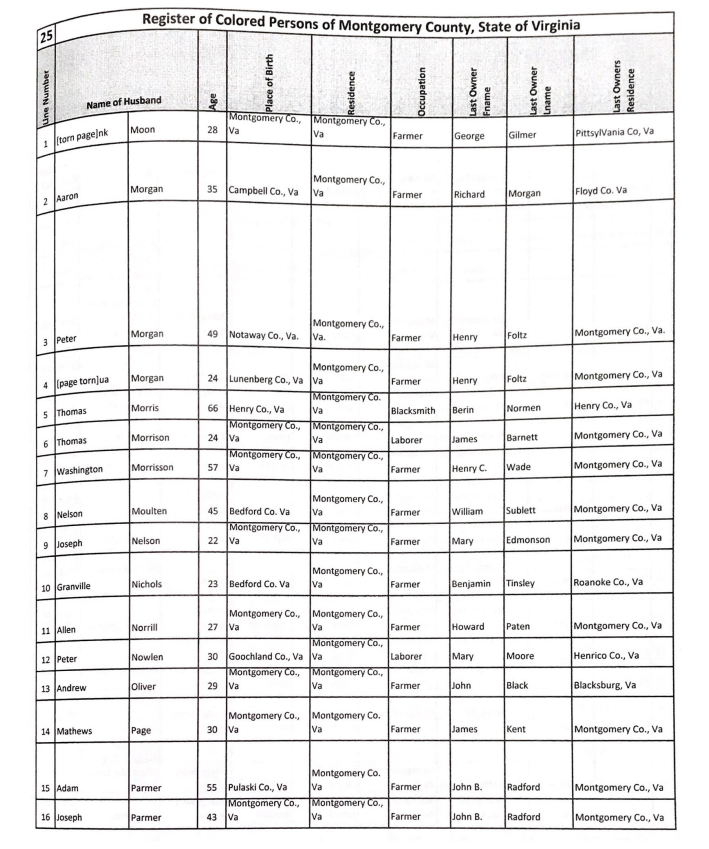

In the Register of Colored Persons Cohabiting Together as Husband and Wife, 27th February 1866, Montgomery County, Virginia, John Black (cousin of Harvey Black) was listed as Oliver’s former owner. The same register dated Andrew’s marriage to Fannie Vaughn as May 1st, 1857. Dr. Daniel Thorp, Associate Professor of History and Dean for Undergraduate Academic Affairs, believes that the spot of the current Graduate Life Center is where Andrew may have worked while enslaved.

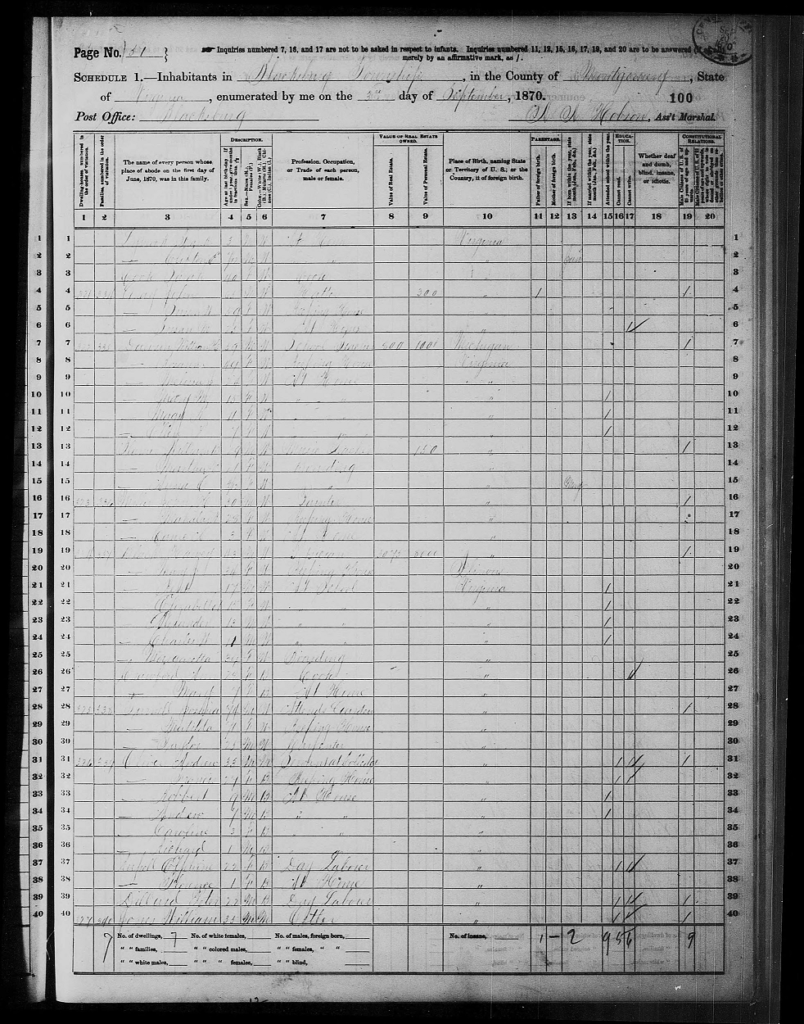

By 1870, Oliver is seen in the US Census, with his occupation listed as “Servant at colledge” (sic) and his race indicated with the letter “M” for mulatto, a period-appropriate word for individuals of mixed white and black ancestry. A researcher can infer that Oliver may or may not have been affiliated in some way with Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College’s predecessor institution, the Olin & Preston Institute (eventually the Preston and Olin Institute after 1869). Although no known photograph of Oliver exists, he is referred to as “the yellow janitor” in the below Techgram article, suggesting he was of a lighter skin tone. If so, this lighter skin tone could very well be why a census taker would list Andrew as being biracial. In every census after the year 1870, Oliver’s race is marked “B,” indicating black.

Further census data sheds light on other milestones in Oliver’s life are brought to light. In 1880, Oliver and his wife had at least seven children – Robert, Andrew Jackson, Callie, Richard, Daniel, William, and Essie – and Oliver’s sole occupation is listed as “Janitor Va+ MC.” By the same year, four other African Americans joined Oliver in assisting the budding college’s everyday activities. Martha Jackson, George Jackson, Louis Smith, and Dennis Ballard are all labeled “servants” in the 1880 census and were believed to have lived in the dormitories of Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College. According to Colonel Harry Downing Temple’s The Bugle’s Echo: Volume I, the Oliver residence would have stood approximately at the site of Randolph Hall. While Fannie “kept house,” Andrew was constantly helping with the University’s upkeep, and per Temple, cadets often called him “the Vice President of the University.”

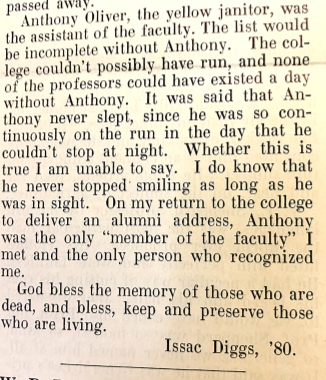

The August 1, 1934 issue of the Techgram, Isaac Diggs wrote of Oliver’s importance to campus in the article “The First Faculty.” Diggs undercuts his kind words a bit in calling Oliver “Anthony” instead of his real name, “Andrew,” but goes on to write that “the list would be incomplete without Anthony. The college couldn’t have possibly run, and none of the professors could have existed a day without Anthony. It was said that Anthony never slept, since he was so continuously on the run in the day that he couldn’t stop at night.”

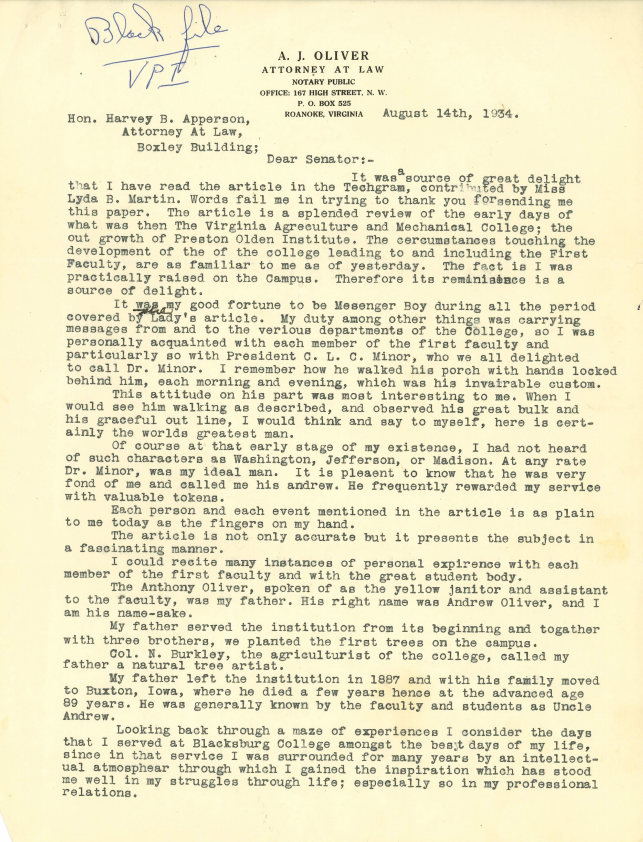

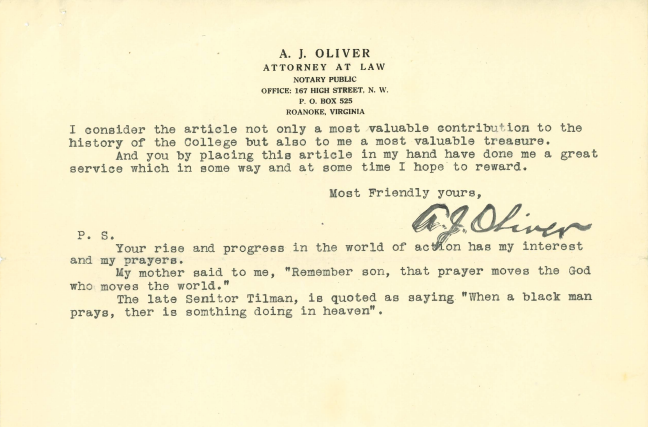

Although Oliver’s legacy is more or less forgotten, there are seedlings of his legacy throughout campus. Andrew and his son of the same name, Andrew Jackson Oliver, helped plant the first trees on campus. Growing up on the campus of Virginia Tech had a lasting impact on Andrew’s oldest son. Andrew Jackson responded in delight to Diggs’ article in the Techgram, noting that the Virginia Tech head agriculturalist Col. N. Burkley, referred to Andrew Sr. as a “natural tree artist.” Andrew Jackson also recalls his own close relationship with Virginia Tech’s first president, C.L. Minor, and mentions carrying messages around campus.

Beyond the mid-1880s, Oliver Sr.’s whereabouts and personal history are more difficult to track. Between the years 1885-1887, it was said that Oliver and his family left Blacksburg for Buxton, Iowa. Dr. Michael A. Cooke, in “Race Relations in Montgomery County, Virginia 1870-1990”, offers a possible explanation for why Oliver may have left. The manuscript notes that mine representatives from Buxton, Iowa traveled south promising black workers an increase in wages; per Cooke, this would equate to around $10 per week compared to the average of $5 per week in Montgomery County. The company, facing a mine strike, also offered black workers free transportation. This led to what Cooke referred to as a “Black exodus” in the New River Valley and a growing black community in Iowa. Although Andrew Jackson’s letter and Temple’s The Bugle’s Echo: Volume I note his father moving to Buxton, census documents also note that Oliver Sr. lived in Jasper County as well (Buxton is noted as a town in Monroe County, IA). Oliver died at the age of 89 in Iowa. The last census completed by Oliver was in 1920. Oliver was listed as being 82 years old and lived on West 2nd Street in Bluff Creek, Monroe County, Iowa with his son Richard, Richard’s wife Rosa, and his grandson, Osea.

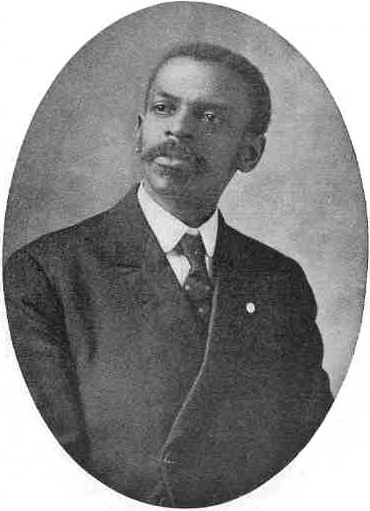

Undoubtedly, Oliver faced unimaginable challenges. His occupations after leaving the college varied, including janitorial jobs as well as coal mining labor. Even in his last days, he never learned to read or write. Through it all, his son Andrew Jackson found much success in later life. Andrew Jackson had humble beginnings and was born during the Civil War. Nonetheless, he was educated at what is now known as the Christiansburg Industrial Institute, the black secondary institution that educated many of the African American residents of New River Valley until 1966. Andrew Jackson also became the first barred black attorney in the State of West Virginia in 1887. Andrew Jackson eventually moved to Roanoke in 1889, where he practiced law by 1890. He was Roanoke City’s first barred black attorney. You can see the letterhead of his firm in the above image. In Roanoke, Virginia, 1882- 1912: Magic City of the New South, Rand Dotson refers to Andrew Jackson as a prominent member of the black community, an attorney, and a minister. His law office “in the white business section of town, also housed his real estate and development firm The Roanoke Building & Land Company.” His second wife, Susan, is also mentioned as a Hampton Institute graduate and schoolteacher.

I post this to remember a forgotten relic of Virginia Tech’s earliest days. Although the first black student did not come to Virginia Tech until 1953, African Americans have always been here, serving as forgotten cogs of a well-oiled machine. Undoubtedly, without their work, Virginia Tech would not be the respected institution it is today. The Oliver family’s history with Virginia Tech is a brilliant embodiment of so many African American stories in the New River Valley: overcoming adversity through hard work and perseverance and leaving subtle evidence of blooming success and towering triumph, much like the trees Oliver planted.