As we’ve moved into the shocking events of March one of my central experiences has been what I would call time dilation. My experience of the passage of time has changed radically. Some of this is the mundane fact that many of the markers of my daily life are falling away or shifting — getting the kids out the door in the morning, getting up and going to work, hitting the gym in the afternoon, various small trips around my neighborhood. Far more though it is what I suspect many of you have experienced: an escalating series of events none of us have any lived experience with and which most of us, I think, could scarcely imagine would ever happen. What’s unthinkable Thursday is quaint by Sunday. Such rapid shifts in our perceptions of the world and reality we’re living in are profoundly disorienting. I suspect more disorienting than many of us yet understand simply because there’s no respite from the rush of events.

With all this I thought it would be helpful to review some of the recent timeline of events, both to get some temporal footing but also to start thinking about the range of possibilities of what might happen and how long this might last.

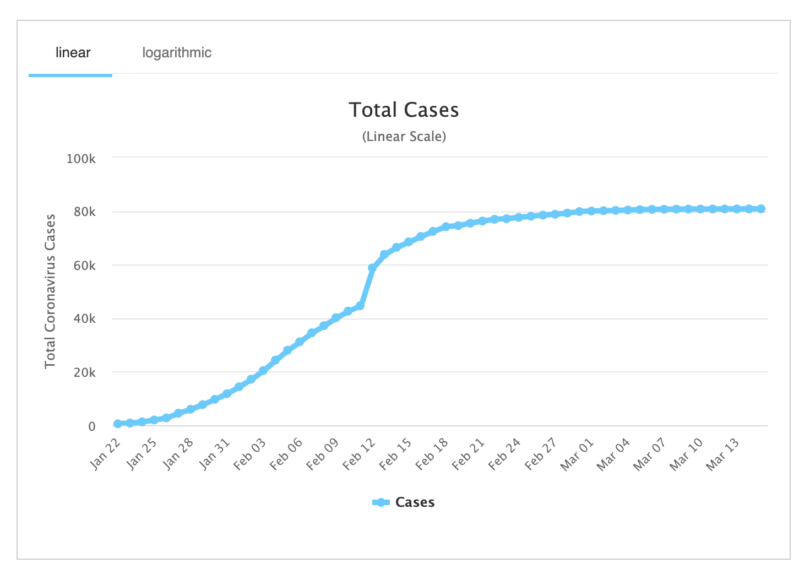

Let’s start at the beginning. An article from three days ago in The South China Morning Post reports that authorities in China have retrospectively dated the first case of COVID-19 to November 17th, 2019. That was 120 days ago. They’re not sure this is Patient Zero. But this gives us a rough date anchor for the beginning of the outbreak. By December 15th there were 27 cases. December 17th was the first day of double digit new cases. The number of infections reached 60 on December 20th.

Here’s a helpful chart.

On January 23rd, there were 571 new cases in China. That was 53 days ago. That was also the first day of the effective lockdown and isolation of Wuhan. You can see that there’s a massive spike of new cases on February 12th. But I believe that is an artifact of when Chinese authorities moved to counting cases on the basis of lung scans as opposed to lab tests. If you set that artifact aside the peak seems to come on February 4th, when 3,884 cases were reported.

By February 23rd, one month after the lockdown the rate of growth had dropped dramatically. The total number of infections topped 80,000 in China on March 1st. That was also the last day more than 200 new cases were reported. That was 16 days ago. By yesterday, March 15th, it had still yet to pass 81,000. (80,866). Still new cases each day but a trickle compared to almost every other country in the world.

In other words, it took China roughly one month from the explosion of cases and the beginning of the lockdown to getting the rate of new cases down to a very low level, effectively controlled if not halted.

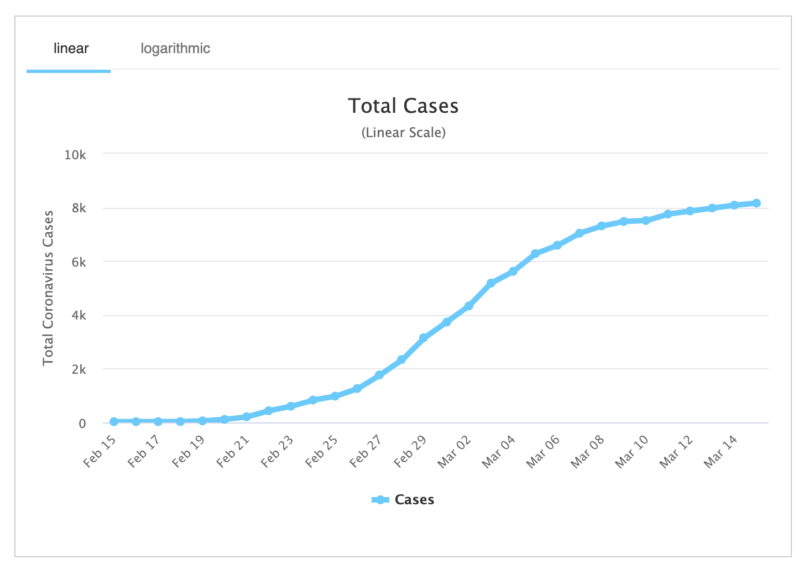

Now let’s look at South Korea.

South Korea looked to be on a disease transmission course similar to those in Hong Kong, Singapore and Taiwan – small, generally contained outbreaks, each of which remains under 250 infections even today. Then on February 17th something went terribly wrong. Patient 31 was a 61 year old woman who first checked into a hospital on February 7th. The key with Patient 31 is that in those ten days, February 10th and February 17th, she attended two services of Shincheonji, a secretive religious group, often considered a cult, which holds worship services with large numbers of people in closely confined spaces. From this woman the South Korean outbreak exploded. That was 28 days ago.

Ten days later, on February 27th, there were 1,766 cases. Ten days after that, March 8th, there were 7,313 cases. The peak of new cases came on March 3rd when South Korea reported 851 new cases. The last day the country reported more than 200 cases on a single day was March 11th. That was 5 days ago.

Let’s step back and see that South Korea’s first day over 100 new cases was February 20th and it’s last day over 200 was March 11th. In other words, 20 days.

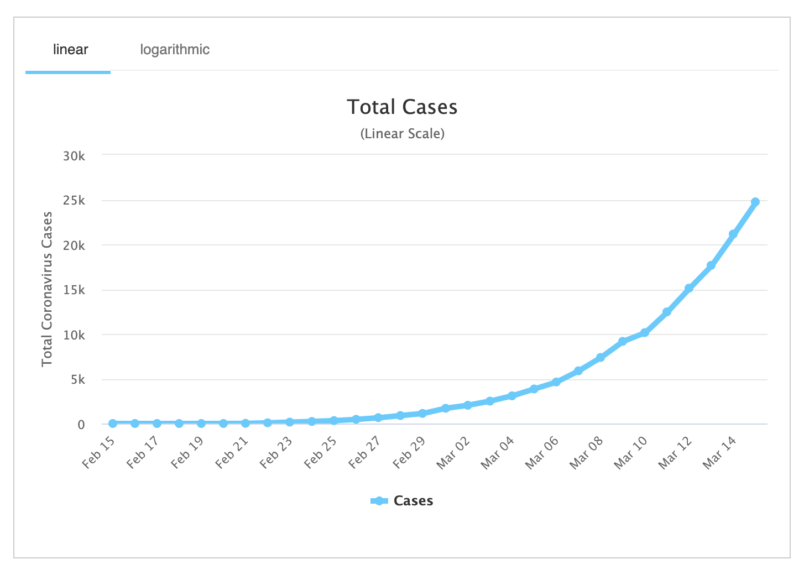

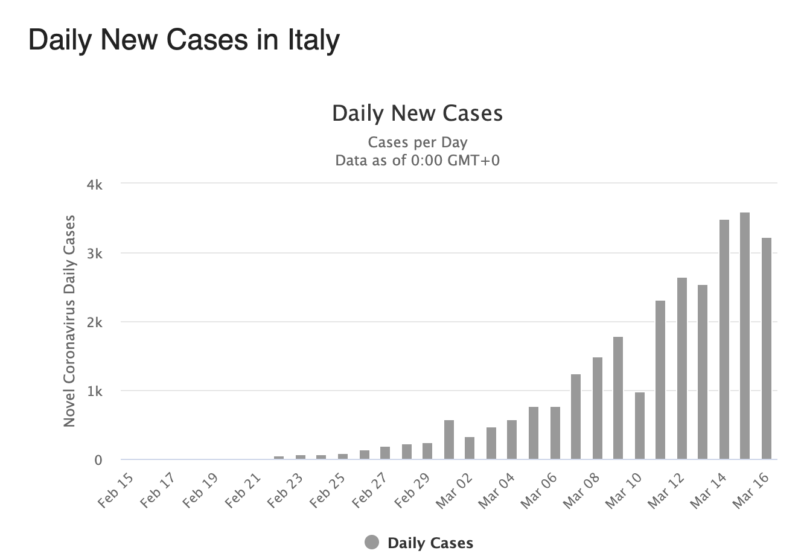

Now Italy.

South Korea’s first day over 100 new cases was February 20th. Italy’s came six days later on the 26th. To date the country’s highest single day of new cases was yesterday when Italy reported 3,590 new cases. Italy has 27,980 cases while South Korea’s plateaued at about 8,000 cases. Italy began its lockdown in northern Italy on March 8th, when cases stood at 7,375. On March 8th, South Korea’s number was almost identical, 7,313. South Korea clamped down much sooner, though the South Korean approach eschewed the total shutdown and isolation of Wuhan. For an early look at the strategy – “aggressively monitoring for infections while keeping the city running” – see this article from the Times from February 25th.

It certainly seems like the contagion roared out of control before Italy quite had a sense what was going on and then only moved toward a dramatic clampdown too late. South Korea on the other hand had a pretty tight hold on the spread of the disease until this one woman exposed herself to hundreds of people at once. South Korea was aggressively monitoring cases before the disease exploded out of control and continued through the outbreak. Making sense of the difference is the work of epidemiological detectives and other scientists.

One point that has only gotten limited attention is that these countries along the East Asian littoral, which have managed the outbreak comparative well, all had the experience of SARS in 2003, if not a lot of infections than an immediate sense of the danger. None bore the brunt of it. But they were on notice and seem to have done a lot of work to prepare for just such an event.

As I was writing this Italy posted its new cases for March 16th, 3,233. That’s a dip from the day previous and some possible hints of slowing but far too early to tell.

Tomorrow is day 121.