WASHINGTON — Some Republicans have said that once they controlled the House of Representatives, they would try to balance the federal budget partly by cutting Medicare and Social Security.

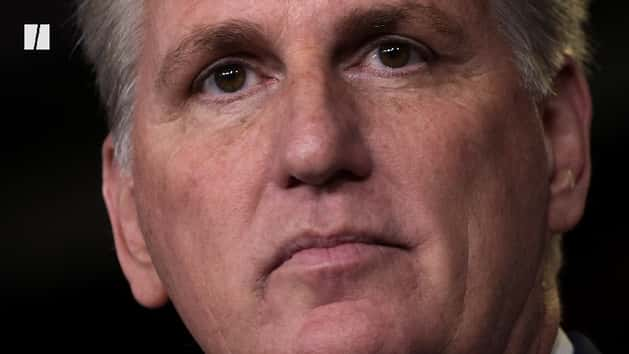

But at the first press conference in his new role, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) could offer no details about their plans for the popular retirement programs this week.

“One thing I will tell you, as Republicans, we will always protect Medicare and Social Security,” McCarthy said in response to a question from HuffPost on Thursday. “We will protect them for the next generation going forward. But we are going to scrutinize every single dollar spent.”

Everybody in Washington wants to “protect” or “strengthen” Medicare and Social Security; it’s a perfectly anodyne statement that a member of any party could utter at any time without thinking.

McCarthy’s answer suggests that Republicans have no plan yet and that his biggest challenge will be trying to get his fractious caucus — which only elected him leader on the 15th ballot — to settle on a unified list of demands.

The purported threat to the programs is the future date at which their trust funds run low, likely resulting in automatic benefit cuts because incoming revenue will be less than what the government expects to have to spend on benefits. Democrats generally favor closing the gap by raising taxes, while Republicans would prefer slashing benefits. Neither party has shown much urgency, however, since Medicare can keep paying full benefits until 2028 and Social Security can until 2035.

But Republicans have declared that they want to use their new House majority to pick a huge fight over the entire federal budget this year. And they’ve already got a hostage: the government’s ability to borrow money and pay its bills.

Sometime this year, Congress will need to raise the “debt ceiling” — the legal limit on how much the Treasury Department can borrow to pay for the spending that Congress has already authorized, including for things like Social Security.

While it’s unclear when the Treasury will run out of borrowing room and face the choice of defaulting by not paying debtholders or people owed by the government, Secretary Janet Yellen fired the starting gun Friday. In a letter, she told senior party leaders on Capitol Hill that she expects the nearly $31.4 trillion limit to be hit Jan. 19.

One potential consequence of a debt ceiling breach? Social Security recipients could miss monthly checks.

Yellen said the Treasury was in the clear until at least “early June,” but the drop-dead date may not be reached until late summer. That’s because the Treasury will be getting a flood of tax receipts in the coming months amid income tax filing season, and it will have a pot of accounting maneuvers it can use — “extraordinary measures” — once it bumps up against the limit. Those will give it several hundred billion more dollars in borrowing room.

Lou Crandall, the chief economist with research organization Wrightson ICAP and a Treasury debt market observer, recently estimated the default date to be sometime in August.

Nancy Vanden Houten, a U.S. economist with research group Oxford Economics, projects that the drop-dead date will come sometime in the third quarter of the year, from July through September. She also noted that this window means it could easily get enmeshed with a likely fight over keeping the government open. Without new appropriations or at least a temporary stopgap bill by October, the government would be forced to shut down all but essential functions.

“Given our current projections, the odds are likely that the need to raise the debt limit will become entangled with the need to pass annual spending bills to avoid a government shutdown on October 1,” Vanden Houten said in a research note.

McCarthy reiterated Thursday that Republicans would use the debt ceiling to negotiate for unspecified spending cuts, likening his plan to good parenting.

“If you have a child, and you give them a credit card, and they spend the limit, so you increase the limit again and again and again — when does it end?” he said. “We have got to change the way we are spending money wastefully in this country.”

(The credit card analogy is common, but weird. Congress both authorizes spending and sets the limit, and lawmakers do so with full knowledge that already authorized spending will eventually surpass it. The limit is arbitrary and not based on some estimate of the nation’s ability to pay.)

So what will Republicans ask for? Though they haven’t coalesced around an actual demand, their position on Medicare and Social Security is not a total mystery. The Republican Study Committee, a policy-focused group of House members that churns out legislative ideas, last year proposed raising the retirement age for both Medicare and Social Security, cutting monthly payments for higher earners and converting Medicare into a “public option” type program that competes in a marketplace against private insurance plans.

Rep. Jodey Arrington (R-Texas), the new chair of the House Budget Committee ― a possible starting point for Republican spending demands ― has said he favors raising eligibility ages for both programs. He told HuffPost he’s hoping to work with Democrats to strike the kind of bipartisan grand bargains that were more common in the 1980s and 1990s.

Arrington acknowledged that cutting Social Security spending may be unpopular, but that’s where Republicans think the conversation needs to go.

“There are a lot of tough decisions for all of us to make across the board,” Arrington said. “The rubber will meet the road with the real decisions about bending the curve on spending and reforming programs.”

It’s possible that Republicans will take aim only at softer targets, such as funding for federal agencies. Rep. Chip Roy (R-Texas), one of the far-right Freedom Caucus members who refused to support McCarthy for speaker unless he promised to go hard against Democrats, told Republican strategist and radio host Hugh Hewitt this week that there could be a “long-term conversation” about Social Security and Medicare after Republicans “slash and burn” some federal bureaucrats with cuts to nondefense discretionary spending.

Even if Republicans shy away from touching retirement benefits, the debt ceiling standoff will be ugly. The atmosphere is already more charged than at the same stage in 2011, the previous time a Republican House tried to negotiate a debt limit hike with a Democratic Senate and White House.

That episode began with then-Speaker John Boehner (R-Ohio) trying to get his new majority — made possible by the Tea Party wave — to agree on what to seek in return for lifting the debt limit. At a speech in New York City that May, Boehner demanded trillions in “actual cuts and program reforms,” an amount that would have been more than the size of a debt hike.

But as the summer wore on and it became clear that neither an all-cuts deal nor a grand bargain mix of spending reductions and tax increases could be made, the fallback was to put in place annual caps on discretionary spending that Congress approves each year — the smaller stuff outside of Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid — in return for boosting the debt limit in increments that Congress would have to vote to cancel.

Those caps only worked the way they were intended for the first year, and then they were loosened in a series of biennial budget deals, making them only modestly effective at restraining spending.

The main immediate impact of the 2011 episode was to cause rating agency Standard & Poor’s to issue a first-ever downgrade of U.S. creditworthiness.

Today, Democrats have so far adopted the position that President Barack Obama took in 2013 when he refused to go through another debt ceiling negotiation. “You do not reward those who will take the debt ceiling hostage,” the Budget Committee’s top Democrat, Rep. Brendan Boyle (D-Pa.), told HuffPost.

Boyle expects Republicans to blink, as they have in previous debt ceiling showdowns. “Every single time, we have managed to raise the debt ceiling. And I think that that history will continue,” he said.

On the Senate side, there’s little patience among Democrats to indulge the House Republicans. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.), a senior member of the Senate committee overseeing Social Security and Medicare, said, “We should not negotiate the full faith and credit of the United States with MAGA extremists in the House” — a reference to the party’s far-right wing. The threat of a default is clear.

Proposals to reduce Social Security spending, such as by raising the retirement age, are political poison, since polls show that most retirees count on the system as a major source of income. That’s why former Republican Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.), a veteran of prior showdowns, said this week that so-called entitlement reform “takes time” and can’t be handled in a single debt ceiling standoff.

Arrington, the budget chair, made a similar remark: “Timing is a lot of it — the right leadership, and getting the public sentiment aligned with what we need.”

But Roy and his faction have sought to be disruptive, and House Republicans weren’t afraid to barrel into an unpopular symbolic vote this week on restricting abortion access. The Freedom Caucus member said it was good that Republicans nearly had a physical altercation on the House floor during McCarthy’s speaker vote.

“We need a little of that,” Roy said on CNN. “We need a little of this sort of breaking the glass in order to get us to the table, in order for us to fight for the American people and change the way this place is dysfunctional.”