2021 Marks Deadliest Year For Alabama Prisons

RECORD DRUG-RELATED DEATHS FROM PRISON CONTRABAND DRIVING FATALITIES

BY BETH SHELBURNE, INVESTIGATIVE REPORTER, CAMPAIGN FOR SMART JUSTICE

Despite the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) lawsuit filed against the Alabama Department of Corrections (ADOC) one year ago on December 9, 2020, people incarcerated in Alabama prisons died from violence and drugs in record numbers this year.

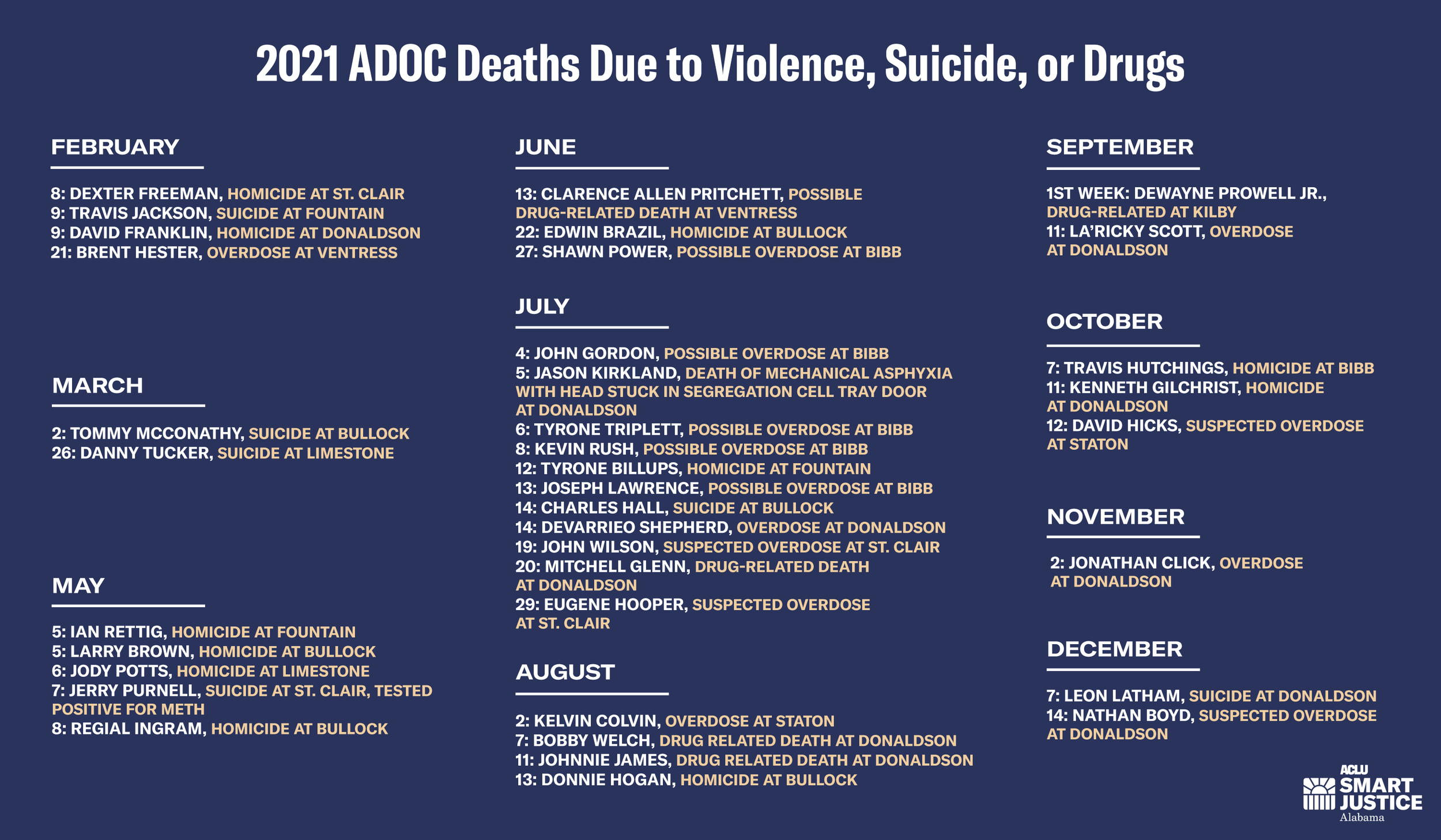

With two weeks still left in the year, at least 37 incarcerated people have died from violence, suicide or suspected drug-related causes in 2021. The same conditions caused 25 such deaths in 2020, 27 in 2019 and 22 in 2018, bringing the total number of lives lost from violence and drugs in a four-year period to at least 111.

In 2021, 11 men were victims of homicide in Alabama prisons, six died by suicide and 19 suffered possible drug-related deaths. The data was compiled from media reports, and independent confirmation through prison sources, county coroners, medical examiners and autopsy reports.

An examination of autopsy reports reveals five deaths were confirmed overdoses and three involved drugs as a contributing factor. The Alabama Department of Forensic Sciences (ADFS) would not release four of the autopsy reports due to ongoing investigations and three requests are still pending. Despite dozens of emails and phone calls asking for confirmation of deaths, ADOC has not responded to any requests in 2021 for this report.

The deaths occurred in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, which restricted those entering the prisons to ADOC officers and staff for much of the year. The agency has previously blamed visitors for some of the contraband brought into facilities, but due to COVID, family visitation was suspended in March of 2020 and only resumed this month at most ADOC facilities.

NOTE: Sources for this data include media reports, county coroners, medical examiners and autopsy reports.

The most common drugs involved in prison deaths were synthetic cannabinoids, methamphetamines and the powerful narcotic fentanyl. July was the deadliest month with 11 reported deaths, eight of them drug-related.

People incarcerated in the prisons say widespread hopelessness among the prison population continues to drive violence, suicides and overdoses. Parole releases remain at historic lows and the few educational and rehabilitative programs inside the prisons were put on hold during the pandemic.

An incarcerated person who asked to keep his name confidential said the proliferation of contraband drugs inside ADOC is a direct result of failed leadership and a culture of corruption inside the agency.

“The management of ADOC has normalized gang activity, drugs and violence,” he said. “We have no security and predatory behavior is rampant. Prison alone causes despair, but it’s beyond (that) when you’re constantly in danger, cannot trust staff and half the people around you are high on drugs. We are trapped in this 24-7 for years on end and that’s why people overdose and kill themselves.”

Even in deaths not directly caused by drug use, many of the dead tested positive for dangerous substances. An analysis of autopsy reports involving 2020 prison deaths shows over 40 percent of homicide and suicide victims had meth, synthetic cannabinoids or fentanyl in their systems when they died.

In 2021, drug-related deaths occurred at four different prisons. The most happened inside Donaldson Correctional Facility where since July, at least seven men died from overdose or as a result of long term drug use. The latest suspected overdose at Donaldson was this week.

“There is so much dope in here, and when guys feel hopeless, getting high is kind of like slow suicide,” said a man incarcerated at Donaldson. “Plus, there’s no guards here. We are so short-staffed, there’s literally nobody here we can go to when we need help. This prison is a ghost town.”

DEADLY DRUGS

La’Ricky Scott was one of the men who died at Donaldson Prison from a lethal dose of fentanyl. He was six months away from getting out of prison in March, 2022 and planned to move to Atlanta and get a job at the airport. Rick, as his family called him, was only 22, serving three years in prison for his first offense that stemmed from a fight.

La’Ricky Scott wanted to be a fashion designer. He died at Donaldson Prison September 11, 2021 of a fentanyl overdose.

During his sentence, Rick obtained his GED and was excited about his future. He had dreams of starting a clothing line and would sketch ideas in a journal he kept with him in prison. Rick was close to his family, which included five brothers. His mother, Delores Scott, is still grieving, but believes the prison is responsible for her son’s death. She wants to know how he had access to drugs and suspects corrupt ADOC staff is to blame.

“Let me tell you, my strength is so weak right now,” she said. “I know I’ve got to gather myself because I’ve got to have justice for my baby. I cannot rest.”

According to the autopsy report, ADOC reported to the medical examiner that on Saturday September 11 around noon, Rick’s cellmate found him unresponsive in his bed and told investigators that Rick had smoked a drug called “Flakka” the night before. Rick was pronounced dead in the prison infirmary 30 minutes later. The autopsy toxicology analysis showed a lethal concentration of fentanyl in his blood. The cause of death: acute fentanyl intoxication. The manner of death: accident.

The following day, his mother was just leaving Wal-mart in Greenville, Alabama when another son, Parrish, called her with the news. Parrish had gotten a phone call from someone inside the prison who told him that Rick died after taking drugs. At first, neither of them believed it was true.

“He can’t be dead,” Ms. Scott told her son. “I’m sure the prison system would get in touch with me and nobody’s called me.”

Parrish encouraged his mother to contact the prison, but she knew she needed support. She drove 30 miles from Greenville to Montgomery to be with Rick’s father in case the news was bad. They called the prison directly and after being put on hold for 20 minutes, the warden finally came to the phone.

La’Ricky was protective of his family, especially his five brothers.

(L-R) La’Ricky, Courtney, Zachary, Parrish, L.J. and Derrick (in front)

“He told me he was deeply sorry that Rick had passed, but he really didn’t know what had caused it,” said Ms. Scott. “He said he would keep in touch with me.”

She said the warden called again after the funeral and sent a card, but never told her Rick’s death was caused by a lethal dose of fentanyl. The Scott family did not know this information until I shared it with them months after Rick died. Ms. Scott has also not received her son’s belongings despite calling the prison multiple times.

“I don’t care if it’s just a pencil, I want it,” she said.

The family also struggles to understand why Rick took drugs in prison when he did not use drugs before prison. Rick had severe asthma and took several medications to help manage the condition. His mother and brother said he typically stayed away from anything that could impact his health.

Rick’s mother and brother described him as a gentle giant, a protector, a quiet person, a sweet boy who wanted to do right.

“He apologized to me a long time ago, just for getting in trouble,” said Ms. Scott. “He said ‘mama, when I get out, I’m going to help you. You don’t have anything to worry about.’”

MYSTERIOUS & DISTURBING CIRCUMSTANCES

Jason Kirkland, 27, also died at Donaldson Correctional Facility on July 5, and his family does not understand the circumstances surrounding his death. According to the autopsy report, Jason died from mechanical asphyxia after a correctional officer found him with his head and arm wedged in the tray slot on his prison cell door, located in the restricted mental health unit of the prison.

An image of Jason Kirkland his mother posted on her Facebook page after he died.

The ADOC submitted a case summary to the medical examiner that states Jason was immediately removed from his cell and transported to the prison’s infirmary, where he was pronounced dead. The last time Jason was seen alive, according to the case summary, was 40 minutes before the officer discovered him while making medication rounds.

“It’s my understanding they are supposed to check on him every 15 minutes,” said Jason’s mother, Connie Nelson. “If they were keeping watch like they were supposed to, they should have caught it before he died.”

The medical examiner reported the autopsy showed “abrasions and pressure marks” on Jason’s body “in locations and distributions corresponding to pressure points from the edges of the ‘tray door.’ Toxicology tests were negative for drugs of abuse or alcohol. “No other evidence or injury to explain death or significant natural pathology was observed,” wrote Daniel W. Dye, M.D., Jefferson County’s associate coroner/medical examiner. He concluded Jason’s death was an accident.

Jason’s remains are still with a funeral home in Birmingham because his family has been unable to pay the remaining balance to cover his cremation.

“I called (the prison) and asked if they could help me and they said no, it wasn’t their problem,” said Ms. Nelson. “I said, ‘but it’s your fucking fault he’s dead.’ They hung up on me after that.”

Jason was diagnosed with schizophrenia in his early teens, right around the time he was expelled from school. Ms. Nelson said he loved to draw, but became withdrawn and depressed and started to act out. The school recommended that she keep him at home.

At 16, the family moved to South Carolina and Jason began talking to a 14-year old girl online. The communication ended with Jason arrested and charged with “attempting a lewd act on a child.” He went to jail and had to register as a sex offender. His family said he never even met the victim in person.

Diagnosed with schizophrenia in his early teens, Jason began cutting himself and self-medicating with drugs after his sex conviction, which stemmed from online communication with another teenager.

After his conviction, Jason became depressed. He began cutting himself and self-medicating with drugs.

“He was a very sweet kid,” said Jason’s aunt, Jammie Bommer. “He had some mental issues but he wouldn’t hurt a fly. He felt neglected, like nobody cared, and that’s why he turned to drugs. Jason didn’t need prison, he needed help.”

When they moved back to Alabama, Jason ended up in prison twice for failing to register as a sex offender. His family said he was using meth and on the streets because he couldn’t find housing. His mother lived near a church and his grandmother lived near a school. He had nowhere to go and despite numerous arrests, no resources were made available.

“I begged a judge to please not send him to jail, send him to a hospital so he can get help, but he wouldn’t do it,” said Ms. Nelson.

A letter and drawing Jason set his mother from prison. He was sentenced to prison time twice for failing to give an address as a registered sex offender. His family says he was homeless because there were no housing options for him in Chambers County.

Jason had only been at Donaldson prison for two weeks when he died. He’d been transferred from Easterling Correctional Facility where he attempted suicide by trying to hang himself with a bedsheet. Ms. Nelson asked the warden if she could visit Jason in the hospital and was allowed a two-hour visit, while Jason was shackled and handcuffed to the hospital bed, the last time his mother saw him alive.

“He was happy he survived,” she said. “He told me he loved me. I don’t believe he was trying to kill himself when he got stuck in the door.”

More than anything, Jason’s family wants someone to be held responsible for his death. Not having any information about the circumstances that led to his death forces them to imagine terrible possibilities: was he killed by a staff member or targeted because of his mental illness? Why would he try to climb through the small slot in his cell door? Was he just trying to get help? Right now they have no answers.

WHERE THINGS STAND

The DOJ lawsuit continues to wind its way through the federal courts. An amended complaint filed on November 19 pointed out homicides in ADOC have increased, and incarcerated people continue to endure a high risk of death. Alabama continues to fight the lawsuit, claiming the allegations fail to articulate “systemic constitutional inadequacies across the spectrum of Alabama’s male correctional facilities.”

Commissioner Jeff Dunn announced he will leave the agency at the end of the month and Governor Kay Ivey named ALEA’s Deputy Secretary John Hamm as his replacement. People hoping for a dramatic change at the top were disappointed.

“Alabama has a culture of locking people up and just throwing them away,” said an incarcerated organizer known as Swift Justice, co-founder of Unheard Voices O.T.C.J. “ADOC and politicians put on a good facade with the public like they are rehabilitating these people, but the truth is, they’re not. These men are just sitting in here with no hope, idle,” he said.

Governor Ivey’s “Alabama solution” to the unconstitutional prison overcrowding, violence and corruption is to build new mega-prisons. Earlier this year she signed legislation to direct $400 million of federal COVID relief toward prison construction. Advocates, including incarcerated organizers, have asked the federal government to prevent this plan of using COVID relief funds for mass incarceration.

“The buildings aren’t the issue,” said Swift Justice. “The existing policies and the culture are the problem. Buildings won’t change that. The buildings have not caused any of these deaths. What ADOC and the Governor can do is give hope back to those inside. Give all who are eligible incentive good time so they can return to society. Give them some agency over their fate and I promise you the violence, suicides and overdoses will decline.”

Beth Shelburne is an investigative reporter for the Campaign for Smart Justice with the ACLU of Alabama. For investigative reporting on Alabama’s prison and pardons & paroles systems, follow her on Twitter at @bshelburne.