UPDATED—The lawyers and family investigating Wanchalearm Satsaksit disappearance in June released a copy of the exiled Thai dissident’s Cambodian passport as investigations in both countries stagnate.

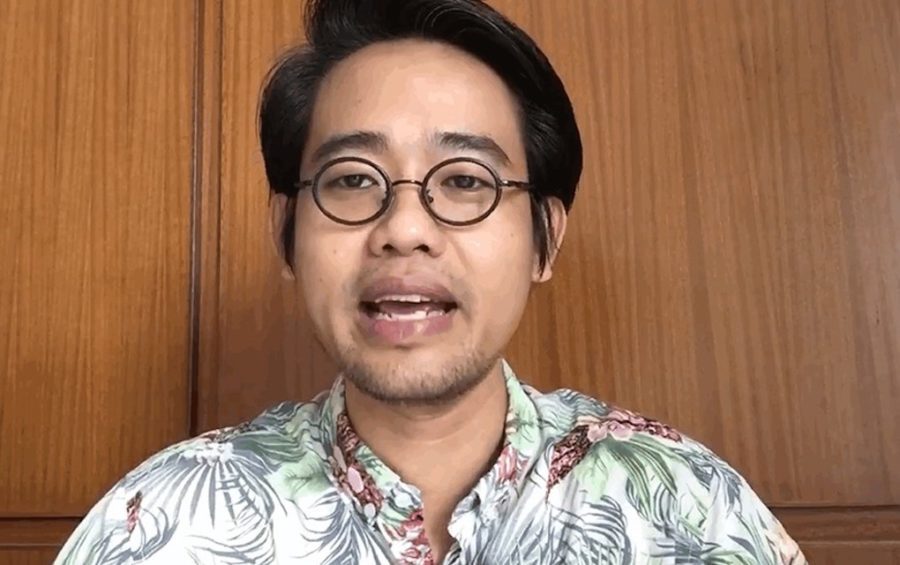

The passport copy, obtained by VOD, shows a picture of Wanchalearm without the usual circle-framed glasses he wore in selfies, with the name “Sok Heng.” The document says he was born in Koh Kong province, and his birthday is listed as August 11, matching a birthday anniversary held last year by his sister, Sitanan Satsaksit, two months after his disappearance. The passport was issued August 21, 2015.

The lawyers also shared a copy of a letter from Thailand’s Technology Crime Suppression Division from June 24, 2018 that orders an investigation into a satirical Facebook page that Wanchalearm ran. That letter notes that the activist lived in the Mekong Gardens condominium in Phnom Penh.

Pornpen Khongkachonkiet, director of Thai non-profit Cross Cultural Foundation and a lawyer on the case, said the team of Thai lawyers decided to release these documents after realizing that Thailand’s Attorney General — which oversees criminal investigations abroad under Thai law — was trying to pass the case to Thailand’s Department of Special Investigations.

“It’s like a hot potato, being thrown in and out” of investigation, she told VOD, adding that the case still had not been given a case number, meaning the Thai government had yet to open an official investigation.

She said neither the lawyers nor the family had the actual Cambodian passport, but Sitanan had seen the passport before.

Sitanan had also been summoned by the Department of Special Investigations, so the lawyers hoped the new evidence would help move the investigation, Pornpen added.

Pornpen said the case was even more stagnant on the Cambodian side, noting that the judge had not made any moves since the lawyers submitted additional evidence, as they were asked to upon leaving Phnom Penh after visiting to investigate and advocate for the case late last year.

The case’s Cambodian lawyer, Sam Chamroeun, said he was still waiting for an investigating judge to issue an order to authorities to investigate the case further.

“I will try to ask for an order to look at, because that order is important for us. It is the heart of the case,” he said, though he did not say when he would ask the judge. “If there is no order, the case will be useless and no clue [will emerge] at all. The clues will come through this order. It is the only way to take action on the case.”

Chamroeun added that the passport copy had already been submitted to the investigating judge, and he could not comment on how its publication could impact the case.

National Police spokesperson Chhay Kim Khoeun said that police had not been told about Wanchalearm’s Cambodian passport, holding to his previous comments that Sitanan and her lawyers did not present police with new evidence when they met in December.

He added that if there are “actual documents or real evidence,” police will investigate the passport.

Interior Ministry spokesperson Khieu Sopheak declined to comment, saying he had nothing to say beyond what he’s said before, which was that Wanchalearm did not have an active Cambodian visa at the time of his disappearance.

Earlier this month, U.N. human rights experts released a letter sent by Cambodia’s U.N. mission on March 3 once again questioning whether Wanchalearm was present in the country at the time of his disappearance.

The letter noted that three Thai lawyers had accompanied Sitanan to meet with a National Police representative to demonstrate that the activist lived in Cambodia, but the letter said “they did not offer any further proofs and details.” It also claimed that “family and the lawyers have not extended to the Cambodian authorities any information or cooperation,” though they gave statements to the Phnom Penh Municipal Court on December 8.

Pornpen, one of the lawyers present in court, on Monday called the Cambodian government’s response “unacceptable,” adding that they had submitted evidence both on January 4 and 19 after a judge requested more information.

“There is still total denial from the Cambodian government. We see that they’re lying to the international community,” she said.

Pornpen said she had not seen any movement on the case by the investigating judge, but there are still leads that could be explored, such as calling in the two guards who witnessed Wanchalearm’s abduction.

But the lawyers are still trying to work with both Cambodian and Thai authorities in order to keep the case progressing, she said.

“We have decided that we need to cooperate with either one, both Thai [authorities] and the Cambodian court, for an official investigation to start, whichever authority will take it seriously,” she said.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the U.N. body that released the Cambodian letter.

Correction: The date that lawyers later submitted evidence to a judge has been amended.

Updated March 30 at 9:04 a.m. with comments from National Police spokesperson Chhay Kim Khoeun.