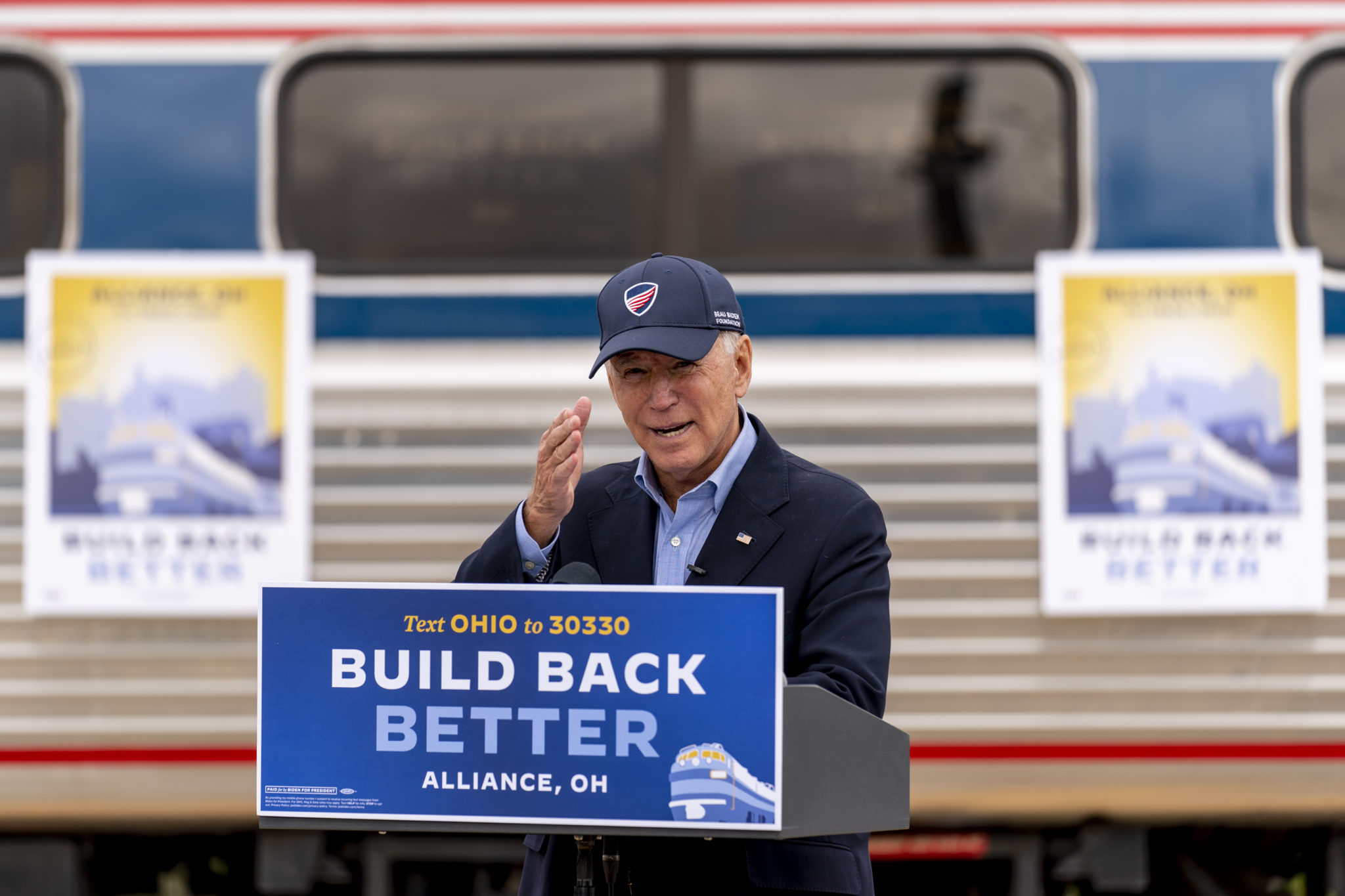

As expected, when a chief executive nicknamed “Amtrak Joe” put together his signature infrastructure bill, it contained an unprecedented sum for expanding rail service across the country: $60 billion over 10 years. Perhaps more surprisingly, it attracted enough support from Republicans to pass the Senate in August. Though as of this writing Democrats in the House are divided over how and whether to tie the bill to other agendas, it seems likely that Biden will eventually realize his ambition to tilt far more transportation dollars toward rail.

It’s a worthy goal. The bill promises to furnish a more convenient and environmentally friendly mode of travel between destinations that are far enough apart to make driving tedious but close enough together to make flying impossible, or at best impractical. You might never use these new trains yourself, but those who do will benefit you by creating less traffic congestion, cleaner air, and a cooler planet. Removing more freight from pavement-pounding long-haul semitrucks onto super-fuel-efficient trains will make driving safer and more pleasant and would yield huge reductions in carbon emissions.

But for any of this to happen on any meaningful scale, the Biden administration will need to do more than just invest more public money in train travel. It will also need to reverse decades of deregulation, lax antitrust enforcement, and other policy blunders that have left modern-day robber barons in control of nearly all the nation’s highly monopolized railroad infrastructure, just as they were in the worst days of the Gilded Age. Only this time, the financiers aren’t presiding over an expanding rail system; they’re selling it off and permanently liquidating its assets for short-term economic gain.

Unless Biden takes on the financiers, even maintaining Amtrak service, let alone expanding it, will become ridiculously expensive. Here’s an example that shows why.

Amtrak for decades offered train service along the Gulf Coast corridor between New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama. In 2005, Hurricane Katrina badly damaged the tracks. The two giant corporate rail systems that own the line, Norfolk Southern and CSX, made the necessary repairs and within a year resumed running their own freight trains. But Amtrak service has never returned.

It is not that people in the region don’t want their Amtrak trains back. A broad coalition of civic and business leaders, including Mississippi Republican Senator Roger Wicker, has been trying for years to persuade the railroads to let Amtrak resume operating. They point to a study by the Trent Lott National Center at the University of Southern Mississippi that says restoring Amtrak service will boost tourism significantly, greatly benefiting Mississippi’s beaches and casinos. They point to the report of a special Gulf Coast Working Group, created by Congress, that estimates the cost of resuming Gulf Coast passenger service at $5.4 million. They point to the fact that the Biden administration, Amtrak, and the state governments of Louisiana and Mississippi are all committed to furnishing the necessary operating funds.

But after five years of negotiations, you still can’t take the train to Gulfport, Biloxi, Pascagoula, or anywhere else along the Gulf Coast. CSX, which controls most of the track along the route, insists that restoring Amtrak service would interfere with the six to eight freight trains it runs daily along the coast. It’s an argument that rail corporations often deploy against passenger service.

The objection is absurd on its face. During World War II, when troop and military freight trains crowded this route along with civilian freight traffic long since lost to trucks, dispatchers still managed to move 11 scheduled passenger trains per day between Mobile and New Orleans. These included the storied “Pan American” of country music fame. And they did it using telegraphs and hand-operated semaphores, not the efficient GPS technology available today.

CSX’s recalcitrance is a negotiating strategy to get Amtrak to either go away or pony up for huge infrastructure investments that would mostly benefit CSX itself. The railroad says restoring two Amtrak trains requires a second main track, new sidings, siding extensions, yard bypasses, and modernization of drawbridges. At one point, CSX put the price tag at $2 billion—orders of magnitude more than estimates provided by the Federal Railway Administration and other independent experts.

Such maneuverings reflect the growing power of hedge funds and other “activist investors” over the railroad industry. In 2017, the financier Paul Hilal used his activist fund Mantle Ridge to buy a nearly $2 billion stake in CSX and win control of its board. Hilal used this power to depose CSX’s long-standing management and replace it with a team of downsizing specialists committed to boosting short-term profits by shrinking the railroad’s physical assets, labor force, and other expenses. The new focus on cost cutting and downsizing has seriously degraded CSX freight operations while also causing the company to take an impossibly hard line with Amtrak.

Exasperated by the railroads’ refusal to negotiate in good faith over the restoration of Gulf Coast service, Amtrak has recently appealed to an independent federal agency, the Surface Transportation Board. But deregulation has left the federal government with very limited control over railroad infrastructure. When Congress and the Nixon administration created Amtrak in 1970, they relieved railroad owners of their previous obligation to provide passenger service at their own expense. Half a century later, the federal government has no clear legal standard to decide when freight railroads must grant Amtrak access to their track, or what the terms of service will be. And since Amtrak owns track only between Boston and Washington and a few other places, dependence on freight railroads is a huge obstacle to improving or expanding passenger rail service.

For example, more than 10 years of studying and lobbying have been dedicated to the question of whether Amtrak will be permitted to run more than one round-trip train per day between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh. Public policy makers must wrestle with many knotty problems; this shouldn’t be one of them. There’s plenty of track capacity. Amtrak ran two round-trip trains along the mostly three-track mainline as recently as 2004. But Norfolk Southern says today that bringing back that second train would create unworkable disruptions to its freight service. The railroad’s latest maneuver was to demand that the state of Pennsylvania pay for a study to calculate how much the public must pay Norfolk Southern for the necessary capital improvements, such as a possible fourth track.

Another example is the drawn-out battle Amtrak and the public had to wage to restore passenger service between Boston and Portland, Maine. By the time Amtrak came into being, passenger service on the route had already been discontinued. To get it started again, Amtrak, as well as state and local governments, had to agree to pay the railroad that owns the tracks tens of millions of dollars for capital improvements. It took another two years of litigation before the railroad, now known as Pan Am, would allow Amtrak to run its trains fast enough so people would want to ride them. A pending mergerbetween Pan Am and CSX now threatens the public’s considerable investment in that passenger route and any prospect of expanding Amtrak service elsewhere in New England.

Biden recently signed an executive order that commanded the Surface Transportation Board to put more pressure on railroads to stop their habitual practice of delaying Amtrak trains by making them wait for passing freight trains. That’s helpful. But the order failed to clarify what rights Amtrak possesses to expand service, and what price it and other public entities must pay railroad owners for capital improvements. Because there’s no clear statutory authority, some industry insiders predict that Amtrak’s legal fight to restore Gulf Coast passenger service will go all the way to the Supreme Court, which could take years. State and local governments seeking to establish commuter rail service have even less legal leverage than Amtrak in negotiating terms with private railroad owners.

It’s much the same story when you consider the prospects for expanding freight rail service in the U.S. Don’t expect much progress unless we claw back Wall Street control.

There’s an overwhelming societal need to divert more freight from trucks to trains. Freight trains are three to five timesmore fuel efficient than trucks and produce far less emissions. Indeed, when electrically powered by overhead wires, trains can be emissions free, and without the environmental and financial costs of battery disposal that plague electric trucks. According to one study, a modest investment in electrifying freight railroads could reduce carbon emissions by 39 percent and, by 2030, remove an estimated 83 percent of long-haul trucks from the road.

Moving more freight by rail would also reduce the number of Americans who are killed or injured by collisions with large trucks, a casualty rate that reached 156,000 in 2018. In addition, it would reduce dramatically the damage done to America’s roads and highways by large trucks—each of which causes the same wear and tear as 9,600 passenger cars.

Yet hedge funds, private equity firms, and other financiers are using their control of highly monopolized, underregulated railroads not to expand rail freight but to sell off rail assets and hand over all but the highest-margin business to trucks.

Some of this downsizing is justified by the decline of the railroads’ thermal coal business as electric utilities convert to natural gas. But most of the downsizing results simply from financiers forcing railroads to shed all but their most lucrative lines of business. Such practices threaten to shrink the nation’s rail network to the point of nonviability, but so long as rail expenses fall faster than rail revenues, the short-term return on assets increases. That’s all Wall Street cares about.

The scale of the downsizing is dramatic. One measure is the rapid disappearance of boxcars. During the 10 years leading up to 2019, even as GDP increased by nearly 50 percent, the railroad boxcar fleet shrank by one-third. Between 2000 and 2019, the trade journalist Bill Stephens reported, the equivalent of 16,132 merchandise freight trains, each with 75 cars, vanished from the tracks of CSX and Norfolk Southern. The main driver of this decline was an industry trend known as “demarketing,” in which railroads actively turn away profitable but low-margin business—for example, hauling grain or consumer appliances—if the move doesn’t involve huge volumes or requires boxcars to be hauled back empty. As a consequence, many farmers now have to use expensive trucks to get their crops to market while many kinds of manufacturing become far more difficult, if not impossible, in the rapidly expanding number of towns and cities where the railroads will no longer do business.

Railroads are also making it more expensive and cumbersome for shippers to realize any advantage from combining shipment by truck with shipment by rail. Especially for trips over about 500 miles, moving containers by both truck and train is much more fuel efficient and environmentally friendly than using trucks for the entire journey. During the 1980s and ’90s, railroads won substantial market share back from trucks in some lanes by offering such intermodal service. But that was before Wall Street started demanding that railroads limit themselves to the highest-margin business.

Bowing to such pressure, in 2018 Union Pacific and CSX discontinued their partnered service on 197 of 301 cross-country container train routes. As a consequence, even shippers who still use railroads to ship containers wind up making much greater use of trucks. For example, if a shipper wants to move a container from any number of western cities to Baltimore using Union Pacific and CSX, CSX will no longer move the container the full distance. Rather, CSX will only take it as far as Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and then make the shipper hire a trucker to haul it the remaining 100 miles to Baltimore.

Railroads have also been stripping out terminal capacity. Wonder why it took so long to get that new car you ordered? The shortage of rail terminal space is a major reason for the widespread logistical bottlenecks since the economy began recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic.

In July, Union Pacific suspended container freight service from West Coast ports to Chicago for a week because it lacked the capacity to sort and redirect the boxes piling up there. The embargo immediately meant that still more boxes coming from Asia with everything from auto parts to transistors piled up on docks as West Coast ports waited for canceled trains. As the chain reaction continued, the steamship line HMM warned customers to expect more delays and announced restrictions on loading containers bound for Chicago. The rail expert Larry Gross calculated that it would take 50 double-stack trains, each carrying 800 20-foot containers, to haul away the pileup caused by just one week of suspended rail service.

Why did this bottleneck occur? In large part because, to appease Wall Street’s demands for higher margins, Union Pacific had previously closed a major handling facility in Chicago, known as Global III, that it now desperately needed to keep the supply chain moving.

Wall Street has also pressured railroads into cutting expenses by reducing the frequency of freight service. If you live near railroad tracks, or if you drive regularly over grade crossings, you may have noticed that railroads run freight trains much less frequently nowadays, and that the trains they do run can stretch as long as three miles. The industry refers to this as “PSR,” or precision scheduled railroading. In practice, PSR has nothing to do making trains run on precise schedules. The term was coined by the late E. Hunter Harrison, a railroad executive who, starting in the 1990s, boosted railroad stock prices through radical downsizing. This made him the darling of hedge funds like Pershing Square Capital Management and Mantle Ridge.

PSR mostly just involves running fewer trains to fewer places using fewer employees, while imposing all kinds of new fees on shippers. After Harrison implemented PSR at CSX, Norfolk Southern and Union Pacific and other railroads imitated him, and freight rail operations deteriorated nationwide. In 2019, Congress held hearings in which shippers relayed example after example of paying more for worse service. Since then, CSX and other railroads have taken PSR still further by ripping out yards and laying off hard-to-replace employees such as locomotive mechanics and engineers. Between 2014 and 2019, before COVID had any impact, the four largest railroads laid off 30,000 mostly unionized workers.

The downsizing was so great that railroads can’t meet the post-pandemic surge of freight shipments. As a consequence, still more freight will crowd onto the nation’s highways. “We can’t let hedge fund managers write the rules of railroading,” complained Oregon Democratic Representative Peter DeFazio, chairman of the House Transportation Committee, in May as he called for an investigation into the way PSR has degraded railroad freight service.

Deregulation and a retreat from antitrust enforcement also feeds the financiers’ control over railroads. Since 1980, the number of major, or Class I, railroads has shrunk from 33 to seven—a number that will drop to six if a proposed merger between Canadian Pacific and Kansas City Southern wins regulatory approval. The result is that more shippers are served by only a single railroad. There are always trucks, of course, but some commodities (grain and chemicals, for instance) are too heavy and bulky to move economically by truck for more than short distances.

Captive shippers once could depend on the Interstate Commerce Commission to protect them from predatory pricing, but in 1980 the Carter administration and Congress stripped the government of almost all its practical ability to do so. The combination of deregulation and lax antitrust enforcement leaves railroads free to hike prices or degrade service standards.

The shippers’ loss has been the railroad stockholders’ gain. Less than three years after Mantle Ridge brought in Harrison to run CSX, the railroad’s stock price doubled. Today, its new CEO says he’s committed to growing the business—but that isn’t necessarily the railroad business. On his watch, CSX bought a trucking company and used a $5 billion stock buyback program to raise the company’s stock price and fatten his own $15 million compensation package. The stock prices of other Class I railroads have also surged, thanks to cost cutting that now allows railroads to spend less than 60 cents for every dollarthey take in as revenue.

This is the industry on which Congress and Biden propose to bestow $66 billion. To protect that investment, we’ll need to do a lot more.

Government played an oversized role in building the nation’s railroads. Historically, railroads operated under charters granted by state and local governments that required them to serve the public good. CSX’s tracks along the Gulf Coast, for example, were originally laid by a corporation created by an act of Alabama’s state legislature in 1866. The legislature gave this corporation government-like powers, including eminent domain to acquire rights of way across the state. But in return, the legislature stipulated that the line must be built and managed in a manner “best adapted to and for the public accommodation.”

This basic relationship between railroads and the public was codified into federal law in the late 19th century and lasted until the end of the 1970s. America’s early railroads received vast grants of public land and other direct subsidies that turned them into local or regional monopolies. In return, American law treated them as quasi-public utilities, subject to strict price regulation and the principle known as “common carriage,” which prohibited them from turning away some customers or classes of business while favoring others.

As Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan wrote for the majority in the 1898 case of Smyth v. Ames,

A railroad is a public highway and nonetheless so because constructed and maintained through the agency of a corporation deriving its existence and powers from the state. Such a corporation was created for public purposes. It performs a function of the state. Its authority to exercise the right of eminent domain and to charge tolls was given primarily for the benefit of the public.

This led to railroads being heavily regulated, first by state railroad commissions and then, after 1887, by the Interstate Commerce Commission, the first federal regulatory agency. The ICC came to wield enormous influence over industrial development by barring railroads from favoring one shipper, industry, city, or region over another. The agency also compelled railroads to provide certain low-margin or even money-losing lines of business, such as branch lines necessary to connect smaller cities and villages to the political and economic life of the nation. By controlling rates and terms of service, the ICC also prevented price wars and other ruinous competition among railroads and gave them a legal vehicle to coordinate operating plans so freight and passengers could travel efficiently across more than one railroad.

Because of the ICC and the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act in 1890, railroads in that era were subject to far more regulation and antitrust enforcement than railroads face today. That’s one big reason why late-19th- and early-20th-century rail tycoons like James Hill or E. H. Harriman concentrated on building and improving railroads rather than on predatory pricing and demarketing like today’s financiers.

This regulatory regime worked reasonably well until the mid-20th century. As the political scientist Samuel Huntingtonwould write in 1952, “During its sixty-five years of existence the Commission developed an enviable reputation for honesty, impartiality and expertness.” But then it began falling apart. As advancing technology expanded transportation by automobile, truck, and air, policy makers should have adjusted transportation policy to take advantage of potential synergies. They could have encouraged, for example, combining trains and trucks to move long-haul freight, or trains and planes to reach out-of-the-way places. Instead, funding was lavished on highway and airport construction.

A telling symbol of this imbalance is Washington’s monumental Union Station, built by a consortium of railroads in the beginning of the 20th century. By the early 1960s, the railroads were paying property taxes on the station of $350,000 a year and an annual maintenance bill of more than $1 million, even as they lost money on passenger train service mandated by the ICC. Meanwhile, across the Potomac, airlines availed themselves of the federally owned and operated National Airport—built, expanded, and operated by a tangle of federal agencies that included the Civil Aeronautics Board, the Army Corps of Engineers, and even the National Park Service.

This imbalance led to massive railroad bankruptcies in the 1970s. Washington at that point might have nationalized the railroads, as nearly every other industrialized nation had done long before. Instead, it bailed out railroad stockholders by allowing railroads to shed public responsibilities such as operating passenger trains and branch lines, while allowing them to engage in a mad merger frenzy.

The strategy saved much of the industry from insolvency, but at a tremendous cost to the public good. Since 1980 the nation has lost more than 40 percent of its rail mileage, as many lines were ripped out that would be invaluable today as we struggle to decarbonize the economy and rationalize our transportation system. And once financiers twigged that Congress had turned railroads into unregulated monopolies answerable only to shareholders, they swooped in and pressured rail management to adopt policies like PSR to further downsize and squeeze out the last drops of monopoly profit.

One solution to this mess would be to nationalize the railroads. The U.S. actually did this, temporarily, during World War I, with many impressive results. Or we could nationalize only rail infrastructure, leaving private companies to operate trains. This “open access” approach has shown promising results in Europe, and it’s not all that different from how the Interstate Highway System works.

Alternatively, we could take a “back to the future” approach, once again treating railroads as utilities but paying better attention this time to coordinating regulation and subsidies among all transportation modes, including new ones like drones and self-driving cars.

The one thing we shouldn’t do, however, if we want to preserve planet Earth and build back a transportation network that suits our needs, is give the railroad industry more money without demanding that it serve the public interest. The looting has gone on long enough.

Research assistance for this article was provided by Rachel Cohen.