WASHINGTON — It sounded like a great deal: The White House coronavirus task force would buy a defense company’s new cleaning machines to allow critical protective masks to be reused up to 20 times. And at $60 million for 60 machines on April 3, the price was right.

But over just a few days, the potential cost to taxpayers exploded to $413 million, according to notes of a coronavirus task force meeting obtained by NBC News. By May 1, the Pentagon pegged the ceiling at $600 million in a justification for awarding the deal without an open bidding process or an actual contract. Even worse, scientists and nurses say the recycled masks treated by these machines begin to degrade after two or three treatments, not 20, and the company says its own recent field testing has only confirmed the integrity of the masks for four cycles of use and decontamination.

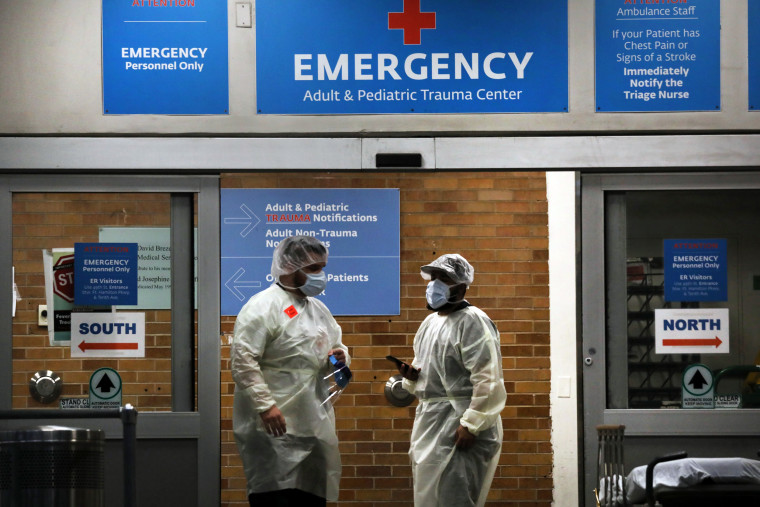

Nurses in several places across the country now say they are afraid of being at greater risk of acquiring COVID-19 while using N95 masks, which they say often don’t fit correctly after just a few spins through a cleaning system that uses vapor phase hydrogen peroxide to disinfect them.

The nurses, who spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retribution from their employers or the government, said they believe the machines, which are made by the Battelle Memorial Institute and have been promoted by President Donald Trump, were rushed into service as a shortcut to acquiring and manufacturing protective equipment.

“It’s a fairy tale,” said one nurse in Connecticut who works at a hospital where masks are run through the Battelle decontamination system. “It’s being done because we don’t have the policies in place to do what needs to be done, and people are going to be hurt because of it.”

As Trump has pushed to find silver-bullet solutions to the pandemic during an election year, the speedy decision to activate the machines reflects yet again the problematic decision-making of the White House task force. As a series of NBC News articles have shown, its leaders have looked past financial costs, potential harm to the public and the risk of getting ghosted by bidders in order to give Trump a steady stream of deals to announce, often with major companies.

“They’re always swinging for the fences hoping that one time they’ll hit a grand slam” and not worrying if they strike out, said one administration official familiar with the work of the task force. “They’re gambling that they’ll win one time, and if they don’t they’ll just deflect, which is what we see inside all the time.”

In weeks of interviews, email exchanges and text messages over the last month with scores of people involved at all levels of the coronavirus response — senior White House officials to front-line responders, career federal officials to scientists working in the field, corporate CEOs to front-line responders — a picture of the task force’s methods has come into ever-sharper focus. Working without external oversight, it has pumped billions of dollars into hard-to-trace contracts for COVID-19 supplies that often don’t pan out as advertised.

White House officials have said often that the president is doing everything he can to protect the nation from the twin emergencies of the disease and its effect on the economy, and Trump and his lieutenants have routinely justified waiving safety and contracting rules by pointing to the need to speed supplies to the front lines of the fight. But critics say Trump has prioritized political ends at the expense of sound science and contracting practices that are designed to protect the public.

“They keep saying these recycled masks are still safe after all these cycles, but we don’t know that,” said a nurse in Pennsylvania, whose hospital has used Battelle’s system. “What we do know is that there are not enough masks for medical workers and there are very real consequences if we get sick.”

Battelle stands by its 2016 study of its technology, which used manikins rather than human subjects to determine whether masks lost their fit or were permeated by particles after 20 uses, according to company officials who responded to NBC News’ inquiries in an email. But the company also said it has only verified the purity of masks for four uses in field testing at Massachusetts General Hospital since the machines were built to respond to a pandemic. That puts health care workers in the position of being the first living experimental test subjects.

“To date, Battelle has received and tested samples representative of four actual use cycles from MassGen,” Will Richter, Battelle’s principal research scientist, said. “The goal of this assessment is to determine the impact of actual wear.”

The pursuit of an all-of-the-above approach to finding medical solutions and equipment to slow the spread of the virus has perversely wasted time, money and opportunity, according to critics within the administration who spoke to NBC News on the condition of anonymity because they fear losing their jobs.

But some lawmakers, former government officials and a handful of current administration officials have spoken publicly in ways that echo and amplify those concerns.

“It’s just outrageous,” Chuck Hagel, a former Republican senator from Nebraska who served as defense secretary under President Barack Obama, said in a telephone interview with NBC News. “Over the course of the last few weeks, what this administration has done, how they have done it with contracts and everything, there’s no transparency, there’s no accountability.”

Battelle’s sanitizers were mobilized by a task force designed to execute on Trump’s demands, despite reservations about safety and cost.

On March 29, Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, slammed the Food and Drug Administration for limiting a waiver of safety regulations for Battelle, which is based in his state. DeWine had lobbied heavily for the waiver in the first place and was upset that the use of Battelle machines was going to be restricted.

At the time, Trump was highly sensitive to criticism from the nation’s governors, having said that week that they should be “appreciative” of the use of his power to help their states. DeWine went to bat for Battelle, which needed looser rules so that its machines could be deployed outside its main facility and used on more than 10,000 masks a day, according to the FDA and DeWine.

The upbraiding of the administration drew headlines, and DeWine said Trump promised him the ruling would be changed. The president even pressured the FDA on Twitter. The broader waiver lifting the limit was announced by the FDA within hours, and DeWine showed his appreciation by thanking Trump and FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn for intervening.

FDA spokesperson Brittney Manchester said that Battelle had originally asked for permission to decontaminate 10,000 masks per day at a single site and that the initial emergency waiver written March 28 covered that. The FDA revised the language after it "learned" the company wanted to use its machines "at an unlimited number of sites with no ceiling on the number of [masks] that may be decontaminated per day," Manchester said.

Spokespeople for Trump and Vice President Mike Pence, who chairs the task force, declined to answer any of NBC News’ questions about the waiver for Battelle, the federal contract and the safety of masks cleaned by the company’s machines. But with the newly revised waiver in hand, Battelle worked with the task force so it could sell its machines to the government.

Technically, the Defense Logistics Agency, an arm of the Pentagon working with the task force, gave Battelle a “contract letter,” which allows for details of a deal to be finalized after the work starts. When DLA officials submitted a legally required justification explaining the parameters of the deal this month, they wrote that the "maximum dollar value" is now $600 million.

The company says it might not hit the cap.

“As demand ebbs and flows at various sites across the country, Battelle will adjust its staffing accordingly and will bill the government only the actual costs incurred,” company spokesperson Katy Delaney said. “If the contract costs are less than the ceiling cost, then the government will not spend up to the ceiling.”

DLA spokesman Patrick Mackin said the $187 million of extra room is there for flexibility."To date, the value of the contract remains at $413M," he said in an email. "The maximum value of the contract is $600M in the event we need to make any adjustments in the support provided by Battelle during the period of performance."

The task force’s deployment of mask sanitizers, several other versions of which have been given an emergency greenlight since Battelle’s went into service, are now part of a transition to a focus on boosting the economy, because the administration insists they reduce the need to supply fresh masks to health care workers. The president himself has said workers have all the equipment they need.

On May 6, Trump told a group of nurses at the White House that reports of PPE shortages are “fake news,” and on May 14, he said he was winding down an airlift program that brought equipment into the U.S. from overseas “because we’re very stocked up.”

But that’s inconsistent with the experience of many front-line workers, according to Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, which represents the second-largest number of nurses of any union in the country.

There’s still a shortage of PPE, she said, which means that health care workers have little choice but to use masks sanitized by the Battelle machines even though “they really believe that N95s should be used once and that’s it.”

It’s “not ideal” she said of the sanitization. “Is it better than nothing? Yes.”

In fact, Weingarten asked top union officials to create a supply chain for personal protective equipment and kept the operation a secret for several weeks until the first batch of masks, face shields and other items began to arrive earlier this month. She said she feared that the shipments would be seized or rerouted by the administration.

Unproven and expensive

When task force leaders convened at FEMA headquarters on April 8, they faced a conflict over whether to proceed with Battelle’s contract despite the sharp price spike.

Trump clearly wanted the mask sanitizers to be deployed rapidly. It had only been 10 days since he tweeted his support for the FDA waiver, which allowed masks cleaned by the machines to be used in health care facilities and freed the company from existing federal quality-assurance regulations.

But from April 3 to April 8, the price had skyrocketed from $60 million to $413 million. An Ohio-based nonprofit corporation that pays top executives more than $1 million a year and spent $350,000 lobbying Congress and federal agencies from Jan. 1 to March 30, Battelle raised the price for each machine from $1 million to $6.8 million “due to the inclusion of operating costs for six months, shipping, and logistics tails to be covered up front,” according to a summary of the decision-making meeting that was circulated to task force members and obtained by NBC News.

The “logistics tail,” a term the military uses to describe the chain of goods and people supporting combat troops in war, broadly refers to the costs of providing supplies and administrative support for a project. The additional $353 million over six months for the logistics tail, which includes the price of employing and training technicians, is equivalent to the retail value of 278 million new N95 masks.

In addition to operating the machines, maintaining them and shipping masks back and forth to health care systems, Delaney said “each site requires things like portable restrooms, showers, protective equipment and in some cases very large tents to house the operations.”

Battelle has performed countless billions of dollars worth of work for the federal government since its participation in the Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb. Much of its work is classified because the company manages eight nuclear labs for the Department of Energy. Battelle also offers private-sector customers in various industries a wide variety of services, including assisting with FDA approval for e-cigarettes. While it enjoys the tax exemptions of a nonprofit, it is a well-established player in the elite spheres of energy and defense contracting, and employs more than 27,000 people.

The company had a powerful customer in the president, and the seven-fold difference between the original estimate on April 3 and the price on April 8 appears to have bothered only one of the senior officials with a seat at the task force’s decision-making table, according to the summary of the debate.

That was Air Force Brig. Gen. John Bartrum, a consultant to the HHS department who oversees the agency’s financial resources, and he raised a formal objection to the task force’s board. He said the government should consider buying 10 of the machines and supporting operational costs for $80 million or $100 million. He advocated for taking time to re-evaluate whether it made sense to go in for the full load, according to the summary of the April 8 meeting.

His concern was consistent with those of a wide variety of federal experts on budgeting, contracting, epidemiology, disease testing, vaccine and drug-therapy development, and public health who have pushed higher-ups to step back and reconsider White House priorities — or at least take more care with taxpayers’ money.

For example, Dr. Rick Bright, who was the head of the federal agency in charge of developing vaccines, testified before Congress last Thursday after filing a whistleblower complaint alleging he was moved from his position in retaliation for objecting to the president’s insistence on purchasing hydroxychloroquine. The drug, which the White House pushed the task force to acquire in tens of millions of doses and which Trump said Monday he has been taking himself, has not been proven to treat COVID-19, and the FDA has issued warnings about its misuse.

But many experts’ voices are being drowned out by the task force’s rush to please a president whose response to the threat of coronavirus was slow and whose recommended remedies have included ingesting disinfectant.

Inside FEMA headquarters, Bartrum was met with resistance by the supply chain unit of the task force, which had recommended the deal in the first place, on the basis that the machines would allow front-line workers to use the same mask up to 20 times. The figure cited was based on Battelle’s study of its own product. The supply chain unit chief, John Polowczyk, has been known to brag that he has a “blank check” from the president and doesn’t care what his group has to spend to acquire goods, according to the person familiar with the task force’s work.

Polowczyk wasn’t present for the meeting, which included senior HHS department, Pentagon, FEMA and National Security Council officials, according to the minutes obtained by NBC News. Members of the president’s National Security Council staff joined the discussion by videoconference.

Bartrum was outgunned. The task force board — FEMA Director Pete Gaynor and HHS Department Assistant Secretaries Robert Kadlec and Brett Giroir — sided with Polowczyk’s team and ordered the purchase to move forward, according to the summary. (Kadlec also clashed with Bright over hydroxychloroquine.)

In a concession to Bartrum, the board said federal agencies should work with Battelle to see if there might be a way to deploy the machines in phases. Two days after the meeting, Battelle and the Defense Department announced the $413 million deal. Over the course of less than two weeks, Battelle had won the emergency waiver from the FDA, struck a deal with the task force, renegotiated that agreement to bring in nearly seven times as much money and released the news to the public.

In justifying the contracting decisions, which ended up raising the cap by another $187 million, Pentagon officials wrote that “under normal conditions, an acquisition with this level of complexity and dollar value would take approximately one year to complete under full and open competition procedures based upon Agency experience.”

If anyone on the task force questioned the company’s statement about the number of times its cleaning machine could treat masks for safe use was reasonable, it was not recorded in the summary of the meeting. Bartrum declined NBC News’ request for an interview through an agency spokesperson.

Retired Adm. Ken Carodine, who worked on logistics at the Pentagon, said in a telephone interview that defense-contracting officials frequently negotiate with companies that bid for work at one price and then jack up the total almost overnight.

“The goal is to never leave,” he said of the practice defense companies use in raising prices to cover employing their workers on government projects for as long as possible. “If anybody should understand the cost of building personal protection equipment and understanding what the entire cost cycle looks like, it’s Battelle.”

Carodine lamented that Pentagon officials routinely refer to defense contract changes of hundreds of millions of dollars as “budget dust” and said that Trump removed a key safeguard with his recent firing of inspectors general who had the power to investigate aspects of the coronavirus response.

“The last person who’s going to take a look is the inspector general,” he said.

‘Real world’ effects

Five days after the deal became public, an NIH-led study concluded that the hydrogen peroxide vapor method of decontamination is only safe for three cycles.

The study, conducted out by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which is run by Dr. Anthony Fauci, used different methods than Battelle’s, according to Dr. Seth Judson, a University of Washington internal medicine resident who worked on the evaluation. The NIH version employed special technology to measure exposure of the virus inside masks and tried to replicate how they would maintain their fit on real people, as opposed to the manikins used in Battelle’s study.

“Since the exposure and testing procedures are different, it is difficult to compare the results, but I think the quantitative testing on people reflects a closer to ‘real world’ situation,” Judson said in an email to NBC News. “Health care workers such as myself may wear these masks for long periods of time, and degradation is seen as masks are repeatedly donned and doffed.”

Battelle agrees that its 2016 study, which did not convince the FDA to approve its technology for commercial use until the president stepped in, didn’t use the same methodology as the NIH version.

“The 2016 study simply reports visual inspections of masks,” Richter, the company scientist, said. “Filtration studies are performed using a TSI 8130A, the industry standard for aerosol performance evaluation. … Testing continues to build a data bank on different makes and models” of masks.

After that study was published, Battelle said, it won approval for a real-world test of its technology.

“The overall conclusion from this study was that three cycles of decontamination did not adversely impact the fit performance,” the company said.

Battelle’s system is already in use by over 400 hospitals across California alone, according to state records, and several other companies have won FDA waivers to deploy mask-sanitizing machines since Battelle was granted its exemption.

Front-line health care workers in Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Idaho and Virginia who have used masks decontaminated by the Battelle system told NBC News they are concerned about their own safety.

“We are worried about how effective our masks are and if we’ll end up catching COVID,” said one Virginia nurse, who like others spoke on the condition of anonymity out of fear of retribution. More “young healthy health care workers are getting it than the general population because we are exposed to a higher viral load.”