Jailed hero of 'Hotel Rwanda' claims he was tortured at 'slaughterhouse' after arriving in Kigali

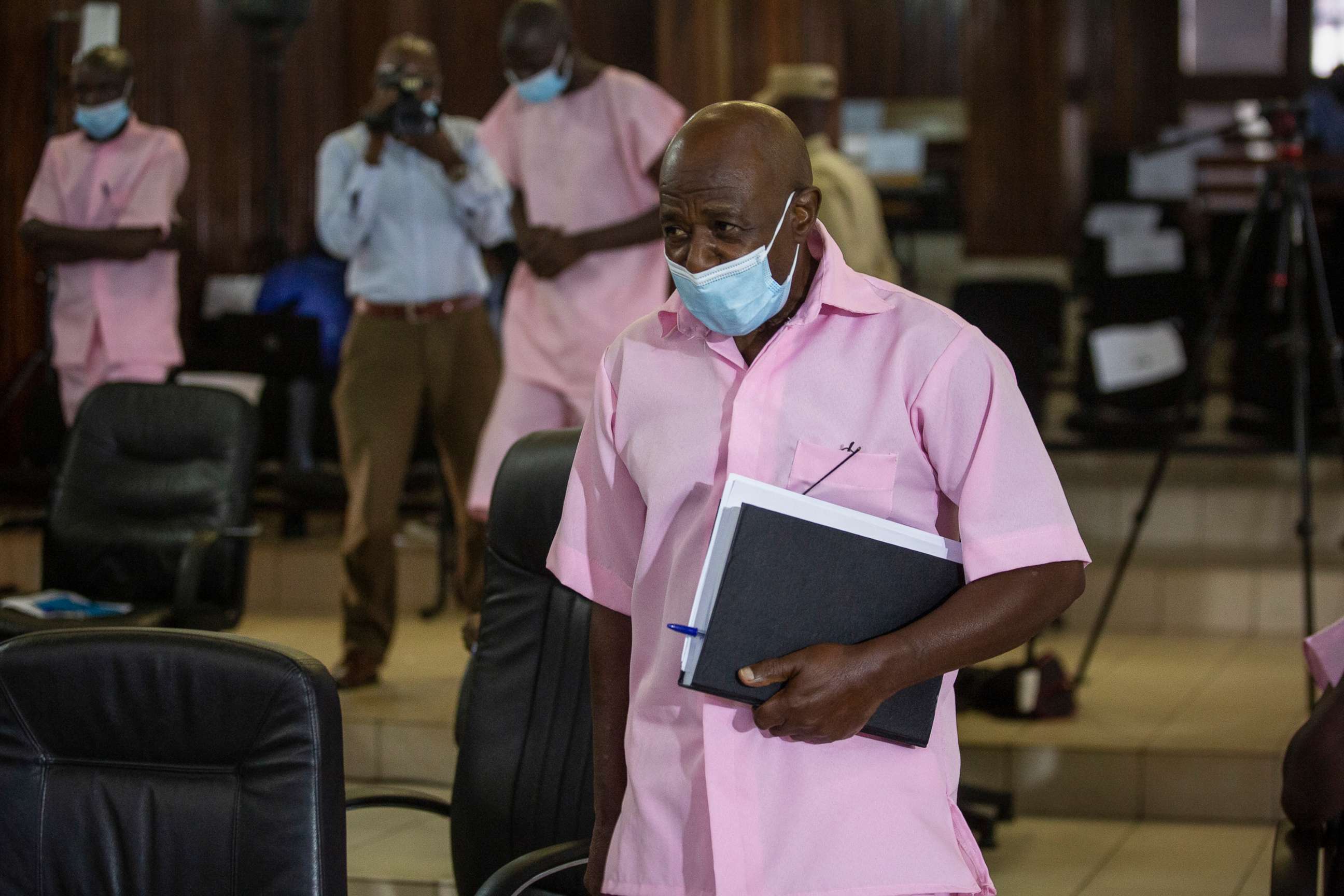

Paul Rusesabagina is on trial for terrorism-related charges in Rwanda.

LONDON -- Paul Rusesabagina, the former hotelier who inspired the acclaimed 2004 film "Hotel Rwanda," alleges he was tortured by Rwandan authorities for several days at an unknown location he described as a "slaughterhouse" after he unintentionally traveled to Kigali last August where he was arrested, according to documents obtained by ABC News.

The previously unshared details of the treatment that Rusesabagina, a 66-year-old cancer survivor, claims he was subject to when he first arrived in Rwanda's capital were revealed in an affidavit of one of his Rwandan lawyers, Jean-Felix Rudakemwa. The affidavit, dated May 3, includes a memorialization of a conversation that Rudakemwa said he had with Rusesabagina in the Kigali prison where he's been detained for nearly nine months while he is tried on a slew of terrorism-related charges. Rudakemwa states in the affidavit that he intended to have a formal statement signed by Rusesabagina, but the situation at the prison "has deteriorated considerably, to the point where I am no longer allowed to visit him with privileged and confidential material in my possession."

Rusesabagina's family and legal representatives submitted the documents Tuesday to update the complaint they filed last September with the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman and Degrading Treatment or Punishment. The new documents were part of an urgent appeal requesting that the special rapporteur, Nils Melzer, intervene to help secure Rusesabagina's release.

"We caution that we have a good faith basis to believe that the extent of the torture suffered by Mr. Rusesabagina is greater than that revealed," Rusesabagina's international counsel said in a letter addressed to Melzer on Tuesday. "We believe the same about the nature and extent of his injuries."

In response to ABC News' request for comment from Melzer, a U.N. spokesperson said the rules and procedures prevent mandate holders from disclosing information regarding submissions received. The spokesperson noted that Melzer has previously sent two joint letters to the governments of Rwanda and the United Arab Emirates expressing concerns of Rusesabagina's arrest.

Rusesabagina, who is originally from Rwanda but is a Belgian citizen and permanent U.S. resident, traveled to Dubai on Aug. 27 to meet up with Constantin Niyomwungere, a Burundi-born pastor who Rusesabagina alleges had invited him to speak at churches in Burundi about his experience during the Rwandan genocide. Later that night, the pair hopped on a private jet that Rusesabagina believed would take them to Burundi's capital, Bujumbura, according to Rusesabagina's international legal team.

Rusesabagina did not know that the pastor was working as an informant for the Rwanda Investigation Bureau (RIB) and had tricked him into boarding a chartered flight to Kigali.

"Myself, the pilot and cabin crew knew we were coming to Kigali," Niyomwungere told Rwanda's high court in Kigali earlier this year. "The only person who didn’t know where we were headed was Paul."

Rwandan prosecutors allege that Rusesabagina wanted to go to Burundi to coordinate with rebel groups based there and in the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo.

According to the affidavit, Rusesabagina told his lawyer that both the pilot and flight attendant said they were flying to Bujumbura. It was not until the airplane landed early on Aug. 28 that Rusesabagina said he realized they were at the Kigali International Airport. Rusesabagina said he then started screaming and tried to get off the jet but was restrained by RIB agents, according to the affidavit.

"They tied my arms and legs, eyes and nose, mouth and ears," he told his lawyer, according to the affidavit.

Rusesabagina’s international legal team, pointing to publicly available flight records, believes the plane was operated by GainJet, which has been used by the Rwandan government and has an office in Kigali. Rusesabagina's family is suing the Greek air charter company for allegedly helping Rwandan authorities kidnap him. GainJet has not responded to ABC News' requests for comment.

According to the affidavit, Rusesabagina told his lawyer that he was taken to an undisclosed facility where he remained blindfolded and bound at the hands and feet until Aug. 31.

"I call that place the slaughterhouse," he said, according to the affidavit. "I could hear persons, women screaming, shouting, calling for help."

While at the "slaughterhouse," Rusesabagina alleges he was deprived of food and sleep and was not allowed communication with his family or lawyers. At times, he said, his nose and mouth were also covered. When his legs would shake due to a lack of oxygen, Rusesabagina said an RIB agent would release the gag so he could breathe, according to the affidavit.

Rusesabagina recalled one instance where an RIB agent allegedly stepped on his neck with military boots. Rusesabagina said he "was hardly breathing" by that point but could hear the agent say, "We know how to torture," according to the affidavit.

Rusesabagina also said he was unable to stand on his own and that someone had to hold him whenever he needed to defecate.

"I lacked strength, I was suffocating," he told his lawyer, according to the affidavit.

Rusesabagina's son appeared to be overcome with emotion as he read parts of the document aloud during a virtual press conference Tuesday.

"Just imagine if this was your own father," Tresor Rusesabagina told reporters.

In response to ABC News' request for comment, an RIB spokesperson said the agency "categorically denies the allegations contained in the affidavit, which contradict sworn statements by Mr. Rusesabagina."

"From the day he was arrested, Mr. Rusesabagina was interviewed by [The] New York Times, [The] East African newspaper, [an] advocate, [the] prosecution, [the] court and never mentioned the torture by RIB staff," the spokesperson said. "RIB is a professional investigative body that respects human rights and does not torture suspects under any circumstances. The case is before the court we shall wait for the outcome."

Rusesabagina's whereabouts were unknown for several days until Rwandan authorities paraded him in handcuffs during a press conference at the RIB's headquarters in Kigali on Aug. 31. According to the affidavit, Rusesabagina told his lawyer that he was interrogated by Rwandan authorities that day for the first time since arriving in Kigali.

Rusesabagina's family and legal representatives have accused Rwandan authorities of kidnapping him and bringing him to the country illegally.

The Rwandan government has admitted to paying for the plane that took Rusesabagina to Kigali, but Rwandan President Paul Kagame said there was no wrongdoing because he was "brought here on the basis of what he believed and wanted to do."

"So there was no kidnap. It was actually flawless," Kagame told Rwanda’s public broadcaster during an interview last September.

The United Arab Emirates has denied having any involvement in Rusesabagina’s arrest and said he left Dubai legally.

Rusesabagina's family and legal representatives said prison officials continue to deny him his prescribed medication for a heart disorder. They said he was also initially denied access to any of his chosen counsel and still has not been allowed contact with his international lawyers. He is provided limited contact with two Rwandan attorneys who are representing him in court. The privileged documents given to him by his lawyers are routinely confiscated in prison, according to his international legal team.

Rusesabagina's lead counsel, Kate Gibson, said his "rights have been systemically violated" and that none of the other detainees in that prison are subjected to such scrutiny and treatment.

"With Paul, the rules appear to have been changed," Gibson told reporters Tuesday.

Rusesabagina was held in solitary confinement for more than eight months, according to his international legal team. However, Rusesabagina's family told ABC News that he was no longer in solitary confinement as of last Wednesday, following media coverage of his detention. The U.N.'s Nelson Mandela Rules state that keeping someone in solitary confinement for more than 15 consecutive days is torture.

"While we are pleased that he is no longer alone, we are still worried about his safety and conditions in prison," Rusesabagina's daughter, Anaise Kanimba told ABC News on Tuesday.

Rusesabagina, a married father of six, was the manager of the Hotel des Mille Collines in Kigali during the Rwandan genocide of 1994, when divisions between the East African nation's two main ethnic groups came to a head. The Rwandan government, controlled by extremist members of the Hutu ethnic majority, launched a systemic campaign with its allied Hutu militias to wipe out the Tutsi ethnic minority, slaughtering more than 800,000 people over the course of 100 days, mostly Tutsis and the moderate Hutus who tried to protect them, according to U.N. estimates.

More than 1,200 people took shelter in the Hotel des Mille Collines during what is often described as the darkest chapter of Rwanda's history. Rusesabagina, who is of both Hutu and Tutsi descent, said he used his job and his connections with the Hutu elite to protect the hotel's guests from massacre. The events were later immortalized in "Hotel Rwanda," with American actor Don Cheadle's portrayal of Rusesabagina garnering an Academy Award nomination for best actor in 2005.

After the movie's release, Rusesabagina rose to fame and was lauded as a hero. He also became an outspoken critic of the Rwandan government.

Rusesabagina's ongoing trial in his home country has captured worldwide attention, with his family and attorneys saying he has no chance at a fair trial and could die from poor health behind bars. If convicted on all charges, Rusesabagina could face 25 years to life in prison. He has maintained his innocence.

"We are, frankly, afraid for our father’s life," Rusesabagina's daughter, Carine Kanimba, told reporters Tuesday.