Executive Summary

Marib, a centrally-located governorate connecting Al-Bayda, Shabwa, Hadramawt, Al-Jawf and Sana’a, has undergone a drastic transformation since the war started in 2015, emerging as a booming economic, social, political and military center. Natural resources including irrigation from the Marib dam and oil and gas reserves were instrumental in building a bustling metropolis in Marib city over a short period. But it was the autonomy afforded by decentralization under Governor Sultan al-Aradah that harnessed those resources for local development. Obtaining its share of the national gas and oil revenues, for example, has helped fund the improvement of infrastructure, pay civil servants’ salaries and build government institutions. Though hardly insulated from the war, Marib has become a haven for displaced people and the last stronghold of the central government in northern Yemen. Its relative stability and success, however, have been threatened by escalating fighting in the governorate, with Houthi forces relentlessly seeking its takeover since the beginning of 2020.

This paper adds color to the monochromatic narrative that has developed around Marib in recent decades by highlighting its rich history, complex social fabric and important role in the national economy. Against this backdrop, the paper examines the factors that have contributed to Marib’s emergence as a pocket of relative stability since the outbreak of civil war in 2015, details the latest attempts by Houthi fighters to capture the governorate and illustrates what is at stake if a Houthi takeover of Marib comes to pass.

Introduction

Marib is located in north-central Yemen, east of the capital of Sana’a. It is surrounded by five other governorates: Al-Jawf to the north, Sana’a to the west, Al-Bayda and Shabwa to the south and Hadramawt to the east. Its location, growing urban center and ample oil and gas reserves make Marib a strategic and highly prized governorate in the war between the Houthis and the government.

Marib’s geography is dominated by mountains and valleys in the west that slope eastward from 2,000 to 1,000 meters into the Ramlat al-Sabatayn desert. It is composed of 14 districts over an area of about 17,400 square kilometers. The governorate’s main urban center and capital, Marib city, lies about 175 kilometers east of Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, near the mouth of Wadi Dhana on the eastern slope of the Surat mountains.[1] Most of the governorate’s population, estimated by the local authority at 2.8 million, live in Marib city.[2] That estimate includes numerous recent arrivals who have fled governorates seized by the armed Houthi movement, Ansar Allah, during the past five years.[3] Prior to the escalation of Yemen’s civil war in 2015, Marib’s population numbered about 411,000.[4]

Long marginalized by the central government in Sana’a, Marib has emerged as a key governorate in Yemen’s shifting balance of power during the ongoing conflict. Oil and gas is by far the highest-value industry in the governorate, though the largest sources of livelihood and employment are agriculture, animal husbandry and beekeeping.[5] More recently, hotels, restaurants, construction companies and other types of commerce associated with Marib city’s urban expansion have grown the economy. Despite more than 30 years of oil production in Marib, the governorate has received only a fraction of the wealth derived from its fossil fuel resources. The central government in Sana’a long had full control of revenues from the lucrative industry. In 2015, after Houthi de facto authorities took control of the central bank in Sana’a, the bank’s Marib branch stopped transferring any revenues, only later renegotiating terms for doing so with the substantially weakened, now Aden-based central authorities. In late 2016, Marib formally secured a 20 percent share of the revenues generated from the governorate’s oil and gas resources, which has fueled the expansion of the capital and the provision of public services for its populace.[6]

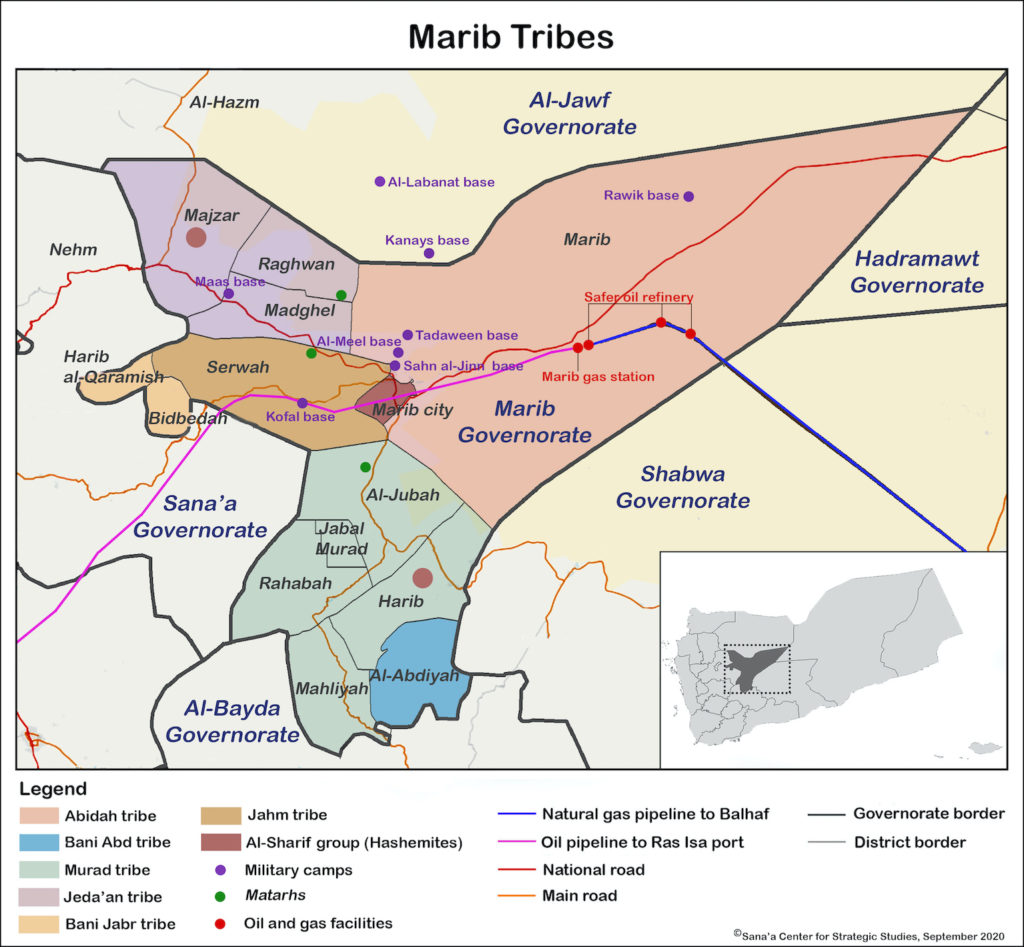

Marib’s indigenous population has a strong tribal identity that has been a large factor in regulating society in the absence of an effective state. There are five main tribal groupings in the governorate: Abidah, Murad, Al-Jadaan, Bani Jabr and Bani Abd. The Abidah tribe has the largest geographical footprint in Marib, staking claim to all of Marib al-Wadi district, which covers the entire eastern half of the governorate. Abidah’s territory encompasses most of the governorate’s oil and gas fields and infrastructure,[7] as well as important heritage sites and a Saudi military base. Marib’s governor, Sultan al-Aradah, hails from the Abidah tribe.

Murad, which is the largest tribe in terms of numbers, has the second-largest geographical reach, predominantly located in five districts in southwest Marib: Rahabah, Al-Jubah, Jabal Murad, Mahliyah and Harib. Murad tribesmen also have a strong presence in government and military leadership. The Jahm tribe, a sub-tribe of Bani Jabr, is concentrated in Marib’s western Serwah district, where heavy fighting between the government and the Houthis has taken place off and on since the start of the war, especially in recent months. Yemen’s main oil pipeline travels through Jahm’s territory in Marib to the Ras Isa oil terminal on the Red Sea. Bani Jabr tribesmen are also located in neighboring Bidbedah and Harib al-Qaramish districts. Al-Jadaan’s tribal territory stretches across three districts in northwest Marib – Majzar, Madghel and Raghwan – which have become active battlefronts since early 2020 when the Houthis seized Nehm district of Sana’a governorate as well as Al-Hazm, the capital of Al-Jawf, and pushed toward Marib. The Bani Abd tribe, located in Marib’s southern Al-Abdiyah district on the border of Al-Bayda and Shabwa governorates, has clashed with Houthi forces since June.

Most of Marib’s tribes follow the Shafei branch of Sunni Islam, except for the Bani Jabr tribe and its Jahm subtribe, which are Zaidi. Since 2015, the tribe has been divided among supporters and opponents of Houthis, who also are Zaidi, as some tribal leaders, most notably Mubarak al-Mashan al-Zaidi, have aligned with the Houthis.

In addition to Marib’s tribes, the Al-Ashraf group[8] represents another important population in the governorate. Composed of a network of families with the surname Al-Sharif, they identify as Hashemites, or descendants of the Muslim prophet Mohammed. Their presence is concentrated in Marib city, as well as in some parts of Harib and Majzar districts.

While Marib’s native residents are not free from rivalries, they have generally put aside their differences and closed ranks to defend the governorate against Houthi incursions.[9]

Historical and Cultural Background

For hundreds of years, Marib’s dominant tribes, notably Murad and Abidah, have lived an independent and isolated life away from the influence of the central state and the power struggles in the highlands of northern Yemen. Eastern Yemen was generally considered remote and did not come under the rule of the Ottomans and the Zaidi imams for centuries.

These two Shafei tribes,[10] in particular Murad, within the framework of the Madhaj tribal alliance, played a prominent role from the 1930s onward in opposing the Zaidi imams of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen, who attempted to assert authority after the Ottomans left the country.[11] In 1948, Sheikh Ali Nasser al-Qardae’i, one of the most prominent sheikhs of the Murad tribe, assassinated Imam Yahya Hamid el-Din, ruler of the Mutawakkilite Kingdom.

Administratively, Marib was grouped with Dhamar from 1933-1941, and then with Al-Bayda during the Mutawakkilite Kingdom (1918-1962) and its successor, the Yemen Arab Republic (1962-1990). Marib became an independent administrative unit in 1974,[12] and was established as a governorate during a Saleh-era 1998 administrative redivision that established the current contours of the governorate. Twenty individuals have run it since 1974, the most recent of whom is Governor Al-Aradah.

Marib has a rich cultural history that stretches back nearly 3,000 years. As the former capital of the kingdom of Sheba, Marib is replete with symbols of the pre-Islamic Sabaean civilization, including the Marib Dam, which dates back to the eighth century BCE. The fortified city was an important trading post along the Frankincense Trail that linked the Mediterranean world and the Arabian Peninsula.[13] In addition to being a political capital and a trading station, Marib was also a religious capital hosting several temples, including the Awam Temple, the largest pre-Islamic temple in the Arabian Peninsula, and Baran Temple, the most famous landmark in Yemen, known locally as the throne of Bilqis, Queen of Sheba. The Marib Dam collapsed in the sixth century AD, forcing the emigration of populations that relied on its irrigation network.[14]

Marib’s heritage sites supported a burgeoning tourism industry until 2007, when a string of kidnappings and Al-Qaeda activity shut down tourism in the governorate.

Marib and the Gulf Countries

Marib has deep historical and family ties with Gulf states, especially Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. After the collapse of the dam in Marib, many of the tribes, most notably much of Al-Azd tribe that used to inhabit Wadi Saba, which is now called Wadi Abidah, emigrated and settled in different parts of the Arabian Peninsula, most of them in what is now Saudi Arabia, Oman and the UAE. Marib shared a disputed border with Saudi Arabia for much of the 19th century. In 2000, with the signing of the Treaty of Jeddah, Yemen annexed Saudi territory north of Marib and included it in Al-Jawf governorate. Saudi influence in Marib remains strong, due to the kingdom’s historical cross-border ties and more recent attempts to curry favor with Maribi tribes to combat Al-Qaeda. In addition to the close border links, Marib has tribal ties with some parts of Saudi Arabia: the Abidah Abrad in Marib and the Abidah Sarat in the kingdom’s southern Asir province belong to the same main tribe, Abidah. These tribes maintain many of the same customs and traditions.[15]

Since the mid-1970s, Saudi Arabia has been keen on establishing political influence in Marib by hosting dozens of Maribis to study in the kingdom and granting tribal sheikhs many privileges. Most of the sheikhs, especially Abidah, have personal relations with the Saudi royal family, to the extent that some sheikhs name their sons after princes and kings. The late Sheikh Ali al-Aradah named Sultan, the current governor of Marib, after the former crown prince, Sultan bin Abdulaziz al-Saud.[16] Among the biggest Saudi-backed projects in Marib was the 2007 construction of the Marib Gas Station.[17] Marib is also of importance to Saudi Arabia in terms of security. Saudi Arabia reportedly had warned Hadi in 2015 not to allow the Houthis to control Marib, considering it a “red line.”[18] The largest number of Maribis outside of Yemen are living and working in Saudi Arabia.[19]

The UAE, for its part, hosts the second-largest number of Maribis living outside Yemen.[20] Marib has been of particular interest to the late UAE president and founder, Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan, since the 1970s, as he considered it the home of his ancestors.[21] In the 1980s, Abu Dhabi funded the rebuilding of the Marib Dam at a value of $80 million; the UAE also has hosted dozens of tribesmen, especially from the Abidah tribe, and granted them Emirati citizenship.[22] After the Arab coalition’s intervention in Yemen, Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed, crown prince of Abu Dhabi and deputy supreme commander of the UAE Armed Forces, invited the sheikhs of the Marib tribes to visit the Gulf country.[23] His son, accompanied by the son of the king of Bahrain and the son of the UAE prime minister, visited Marib while participating in coalition operations against Houthi forces and met with tribal leaders.[24] The biggest base of the Arab coalition in Yemen, which included the headquarters of the Saudi and Emirati leadership before the latter withdrew in 2019, is located in the Tadaween area of Marib, about 10 kilometers northeast of Marib city.

Marib during the Saleh Era, the Hadi Transition and Now

Marginalization and Saleh’s Game of Divide and Rule, Fueling Tribal Conflicts

Yemen’s first major commercially exploitable oil reserves were found in Marib in the 1980s, and since then the governorate has remained one of only three Yemeni governorates producing hydrocarbons. Marib is also the site of Yemen’s largest electric power plant, built to power the national grid. For decades, however, Marib gained little benefit from its status as a relative energy hub in the country. While all of Marib’s oil revenues were deposited in the Central Bank of Yemen in Sana’a to help fund the national budget, the governorate’s share of the budget for public services and infrastructure was inadequate and rarely paid in full. With limited central government support and denied the benefits of its own natural resources in the oil and gas sector, Marib remained underdeveloped.

However, some tribal leaders in Marib were beneficiaries of Saleh’s largesse, as part of the former president’s attempts to influence local communities through co-opting influential figures. Oftentimes, the loyalties of these co-opted leaders did not lie with their local communities. Rather, their loyalties were purchased to do the bidding of Saleh’s political ambitions. This included rallying tribal fighters to weaken another tribe if it was considered a threat.[25]

Apart from the Saleh regime actively fueling conflict with guns and cash, the broader neglect of Marib has itself been a source of conflict in the governorate. In the first decade of the new millennium, increasing water shortages in rural Marib fueled tension on a variety of fronts, according to a 2011 conflict assessment by Partners Yemen and Partners for Democratic Change International. For populations reliant on farming, unequal access to water made it more difficult to grow food. For example, half of Serwah district in western Marib was regularly at risk of water shortages due to the absence of proper irrigation networks and a lack of access to wells. Meanwhile, water shortages at that time, which displaced residents of southwest Marib near the border with Al-Bayda, were blamed for tribal violence that killed nine people and injured 10 others.[26]

Unemployment, cited as a major cause of conflict in Marib, led to roadblocks, violence, vandalism and gang membership, according to the conflict assessment. A lack of teachers, health workers and hospitals was described by locals as another serious problem in Marib.[27]

Rather than building a state presence in Marib, Saleh empowered tribal sheikhs to help protect oil and gas pipelines and electric power lines. Granting regular financial transfers led to the formation of a tribal elite that benefited from the absence or weakness of the state. During local elections in 2006, no real competitive elections were held in most districts of Marib. Rather, district representatives were chosen by tribal sheikhs loyal to Saleh.[28]

Police, courts and other justice services were never widely accepted in most tribal areas, including Marib. Instead, other local authorities including imams in mosques and tribal leaders would resolve disputes. While tribal customary law has tended to prevail as a means of conflict resolution in many areas of Marib, some locals suggested that respect for tribal customs was waning among younger generations.[29]

In the last decade, however, a youth movement has pushed back against central government practices with demands that community issues be addressed. When popular protests took root in Taiz and Sana’a in 2011 demanding the removal of Saleh from power, Maribi youths led local demonstrations. From a tent in Marib city, they organized civic education sessions, social media activities and held regular protests. Even after Saleh resigned, dozens of youths from Marib’s main tribes kept up their activism. Over the next two years, they launched the Marib Cause Initiative and the Sheba Movement (al-Harak al-Saba’ie), which addressed community issues, arranged tribal gatherings and sit-ins and demanded a share of oil and gas revenues for local development projects.[30]

Strikes Targeting AQAP Viewed as Attempt to Distract from Tribal Demands

In 2010, the Saleh regime increased coordination with the United States in a series of counterterror operations in Marib that angered local tribesmen, especially when civilians were killed or homes and farmlands damaged. Botched military operations, like the May 2010 drone strike that killed Marib’s deputy governor, Jabir al-Shabwani, were met with calls for justice and revenge attacks on oil pipelines and electricity infrastructure feeding Sana’a.[31]

These acts of retaliation, according to two Maribi tribal sheikhs, were often incorrectly interpreted as widespread tribal support for Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).[32] While a small minority of tribesmen sympathized with Al-Qaeda and sought to take revenge against the former regime, tribal sheikhs in Marib interviewed for this report indicated such sympathy existed more on an individual basis.[33]

Tribal leaders accused the central government of using the war against Al-Qaeda to deliberately defame and demonize the tribes of Marib, who had started raising their voices against the marginalization of their oil-rich governorate. Counterterrorism operations helped distract attention from these grievances and were viewed locally as a way for Saleh to get support from the United States at the expense of the tribes.[34]

Most of the AQAP-affiliated militants targeted in Marib have been from outside the governorate, according to the tribal leaders. AQAP used the open desert that spanned parts of Shabwa, Al-Jawf and Marib governorates to carry out attacks and retreat, rather than control territory, they said, adding that tribes generally ejected members who joined AQAP.[35] AQAP and its affiliate, Ansar Al-Sharia, later seized control of cities and towns in Abyan, Shabwa and Hadramawt governorates between 2011 and 2016.

A New Era under Al-Aradah (2012–2014)

Yemen entered an uncertain political transition period in 2012, when Saleh reluctantly transferred power to his deputy, Abdo Rabbu Mansour Hadi, as part of a GCC-brokered deal following a year of Arab Spring-inspired protests. As the Saleh regime exited and a new one attempted to rise in its place, Yemen’s social contract was being renegotiated. Amid this revolutionary change, long-marginalized groups let their grievances be known. In Marib, the combination of strong, independent tribes, virtually no state presence outside of the capital and a few other towns, along with the creeping presence of Al-Qaeda, posed a unique threat to the political transition.

This was the situation when Hadi appointed Al-Aradah as governor in April 2012. A former army general and member of parliament in the General People’s Congress (GPC) party hailing from Marib’s dominant Abidah tribe, Al-Aradah started his new role by strengthening the executive offices in the governorate — assigning new managers and requiring regular departmental meetings, following up on performance, especially in public service sectors, and reaching out through local radio to raise public awareness of available government services. Unlike his predecessors, who spent most of their time outside the governorate, Al-Aradah had a semi-permanent residence in Marib which gave him a clearer view of the security situation, development and social concerns. As such, his main focus was on improving the security situation and then providing basic services such as electricity, education and health.

On the security front, the governor enhanced coordination between police and army forces, which had previously operated independently. At the same time, Al-Aradah intensified meetings with tribes like Al-Jadaan and Jahm, through whose territory electricity lines, oil pipelines and main roads pass, to listen to their grievances.[36] The governor signed tribal agreements to protect public infrastructure from attacks.[37] To address a root cause of some of the attacks, Al-Aradah’s local authority provided electricity generators for several districts for the first time.[38] It is unclear how much Al-Aradah’s public outreach helped in reducing the attacks. Over the next two years, Al-Qaeda continued to carry out operations in Marib, while disgruntled tribesmen (many of them Abidah) and criminal groups regularly sabotaged oil pipelines and electricity infrastructure that powers the grid in Sana’a to demonstrate their leverage in extracting concessions from the new central government on issues including development.[39]

Tribes and Politics

Politically, the Murad tribe is considered a center of influence of the General People’s Congress party in Marib, and it has the largest presence in state structures — civil, military and security — of any other tribe in the governorate. Several influential leaders in Murad are loyal to the GPC, particularly Sheikh Ali Nimran al-Qabli. His son, Abdul-Wahid, leads the GPC party in Marib and has played a significant role in fighting the Houthis since 2015.

The Abidah tribe is deemed the center of gravity for the Islah party in Marib, and it has the second-largest presence in civil departments. Abidah’s shift toward Islah has been relatively recent. A number of prominent Abidah tribesmen were GPC, and Abidah areas historically voted GPC in parliamentary elections. But after the war began and former President Saleh allied with the Houthis, Abidah leaders loyal to the GPC didn’t follow him. With Saleh’s 2017 death and the 2019 death of a prominent tribal leader, Sheikh Mohsen bin Mayli, GPC support in Abidah areas has gradually weakened and shifted to Islah.

Despite political differences, tribal identity remains stronger and more influential than party affiliations and any other factors. Al-Aradah has administered the government by taking into account tribal balances before political considerations. His understanding of the nature and composition of Marib’s society is rooted in decades of experience in resolving tribal conflicts as well as the political experience he gained in parliament and within the GPC party.

Since the outbreak of war, members and leaders from different political parties, mostly Islah and GPC, have fled areas under Houthi control to Marib, where many joined the ranks of the resistance and the national army. Islah has been accused by some Murad tribesmen of trying to expand its influence and power by installing loyalists from outside Marib in the army ranks to the exclusion of others.[40]

In mid-January of 2015, the two rival political parties issued a joint statement declaring their support with Maribi tribes to defend the governorate. The local branches of the GPC and Islah agreed to form an alliance aimed at preventing Houthi forces from entering the governorate. Despite political and tribal differences within the governorate, Marib’s populace has generally formed a united front in the face of the armed Houthi movement, considering it an existential threat to their land and interests.

From Backwater to Beacon of Relative Stability: Marib Benefits from War

After gaining control of Sana’a city and most of Yemen’s surrounding highlands, the Houthis, then allied with former President Saleh and his affiliated forces, headed east toward oil-rich Marib governorate in March 2015. The local authority, political parties and most of the tribes in Marib had rejected what they called a coup against the legitimate Yemeni government and stopped dealing with the Houthi authorities in Sana’a. Tribal leaders from the Jahm tribe were divided between supporters and opponents of the Houthis, due to their common Zaidi Shia affiliation. Likewise, many Al-Ashraf also sided with the Houthis because of a shared Hashemite background, though many maintained their positions in civil departments of the local authority. All of the prominent leaders of the Abidah tribe opposed the Houthis as well as most of the influential leaders in Murad. Only one prominent Murad sheikh, Hussein Hazeb, along with a few minor Murad leaders, aligned with the Houthis. All of the prominent tribal leaders in the Jeda’an and Bani Abd tribes also opposed the Houthis.

Houthi leader Abdelmalek al-Houthi justified the 2015 offensive against Marib by warning that the local authority was going to allow the governorate to fall into the hands of Al-Qaeda.[41] In 2014 and 2015, AQAP operative Ghalib Al-Zaidi had helped the group expand into parts of Marib, recruiting new members and accepting loyalty pledges; in 2015, he obtained financing and weapons for operations against the Houthis, according to a UN Security Council’s 2017 announcement of sanctions against Al-Zaidi.[42] He led AQAP fighters in Marib until being killed in August 2018 in Serwah, his home district, in a battle against Houthi forces.[43]

Influx of Refugees and Businessmen

Large-scale Houthi attacks on Marib began 0n March 10, 2015. Their forces were able to advance into territory in the west and northwest of the governorate, but failed to reach Marib city. They were confronted by military units and tribesmen, the latter of which had been massing fighters and weapons since late 2014 in preparation for confrontation with the Houthis. The fighting continued until September, when army reinforcements and the Saudi-led coalition arrived and helped reestablish control in most of the areas the Houthis had entered.

After thwarting a wave of intensive Houthi attacks to control Marib later in 2015, Marib’s local authority shifted its attention to mitigating the effects of the war. The relative stability that emerged in the governorate made it a refuge for those fleeing areas affected by the conflict or under the control of the Houthis.[44]

During the first year of the war, the local authority in Marib said the governorate received 1.35 million internally displaced people (IDPs), nearly tripling the size of its pre-war population of about 411,000.[45] Most of the people who have fled fighting and moved to Marib since 2015 have come from eight governorates: Sana’a, Amran, Dhamar, Hudaydah, Al-Jawf, Ibb, Taiz and Hajjah.[46]

The majority of the new arrivals settled in the governorate’s capital, Marib city, which had fewer than 49,000 residents prior to the war.[47] The rapid population increase put tremendous pressure on the governorate’s limited infrastructure and public services.

One of the immediate challenges that emerged from the influx of new residents was an acute housing crisis as rental prices rose to unprecedented levels. In early 2020, one resident of Marib city reported a 10-fold increase in rent per month for his two-room apartment, compared to before the war. The construction of four massive IDP camps in the governorate and others in neighboring governorates has not curbed the growing rental rates, according to a humanitarian worker there.[48]

The local authority managed the growth of Marib city with little outside help in the early years of the war. International aid organizations didn’t establish a meaningful presence in the city until 2018, according to the top local official in charge of displaced people.[49] Even then, the local authority has complained about ineffective intervention from the international humanitarian community.[50] As of early August 2020, there were 143 IDP camps throughout the governorate that housed about 475,000 people, the official said.[51]

Marib natives generally have welcomed IDPs, despite mixed feelings about the rapid growth of the city. A few residents said in interviews that IDP-fueled growth is encouraging for the indigenous population, which had been reluctant to establish projects, whether public or private, due to instability and a lack of economic activity.[52] At the same time, IDPs are viewed as competitors for jobs, housing, education and humanitarian aid.[53]

Autonomy and Decentralization; Maribis Secure Share from Oil and Gas Revenues

By the time the Houthis routed President Hadi and his government from Sana’a in early 2015, Marib’s local authority, security committee and the leaders of local political parties had convened an emergency meeting to discuss the future of the governorate. With the Houthis and Saleh in power in Sana’a, the officials at the meeting authorized the local authority to manage and administer the affairs of the governorate in line with the outcomes of the National Dialogue Conference (NDC).[54] The NDC, launched in 2013 to guide the political transition led by Hadi and address Yemeni social and political grievances, had recommended dividing Yemen into six federal regions in which local authorities were given more independence and powers to govern. Marib, Al-Jawf and Al-Bayda governorates together formed the Saba region, with Marib as its capital.

Securing income from its oil and gas resources has greatly helped Marib exercise its autonomy in decision-making. Marib for years has supplied Yemen with most of its domestic gas needs, and a significant portion of the country’s oil requirements. The local branch of the Central Bank of Yemen (CBY), as required by law, had been sending Marib’s oil revenues to the Sana’a-based CBY headquarters until November 21, 2015, when the governorate announced financial and administrative disengagement from Sana’a.[55] According to a local official in Marib, after the disengagement, all oil and gas revenues were deposited in an account at the Marib branch of the Central Bank.[56] In late 2016, Governor Al-Aradah announced that the local authority had negotiated an agreement with the Aden-based government, which provided for a restoration of 80 percent of the revenues to the central government and for the local authority to keep a 20 percent share of oil and gas revenues generated from Marib for development.[57] It marked the first time Marib had officially secured a share of its natural resource wealth since the discovery of oil there in the 1980s. Eventually, the central government’s share of revenues was brought under the control of the CBY in Aden, through the June 2019 linking of the Marib branch to CBY-Aden.[58]

The new source of income from oil and gas revenues has allowed Maribi officials to rebuild state institutions and spur the expansion of public services in the governorate. The local authority has also been able to respond quickly to emergency situations in the governorate, like the floods of August 2020. Al-Aradah allocated 100 million Yemeni rials to each district from the governorate’s coffers to address damage caused by torrential rains and flooding of Marib’s dam.[59] Previously, local authorities would have had to request emergency funds from the central government.

The funds also have enabled a number of locally implemented state-building and development projects, including the rebuilding of local security forces, the establishment of a relatively functional judicial system and the construction of Saba University, new roads and a sports stadium.[60]

In addition, oil derivatives markets have witnessed relative stability in Marib, as fuel products are produced and refined locally and cover local needs in the governorate. This stands in sharp contrast to other areas around Yemen which at times suffer from a shortage of oil derivatives and wild price fluctuations. In Marib, petrol and cooking gas are almost always available at official prices,[61] while gas tankers leave the governorate to the capital Sana’a and other governorates on a daily basis.

Building Security Forces and a Judicial System

Prior to the war, there was virtually no state presence in the governorate outside the capital. Marib city had one court, one police station and underpaid, corrupt and ineffective weak security services.[62] With its newfound revenues,[63] the local authority prioritized the reorganization of the security forces and reactivation of judicial institutions. Having lost Sana’a and still weak in the interim capital Aden, the central government backed these developments in Marib, which was emerging as a power center in northern Yemen.

Rebuilt in coordination with the central government’s Ministry of Interior, Marib’s security services resemble those in Yemen’s major urban centers. Chief among them are the Special Security Forces (SSF), formerly known as the Central Security Forces, which are charged with guarding major cities.[64] The SSF have trained and graduated at least nine new batches of recruits since 2016 to secure Marib city’s growing population. Patrol officers, road security (al-Najdah) and traffic police have also added new cadets, including female police officers for the first time in Marib.[65] Criminal investigation and civil defense units are also operating in the governorate.

With some help from the Saudi-led coalition, the local authority has trained and provided the security forces with vehicles, weapons, supplies and offices.[66] There are now fivef police stations in Marib city, compared to one before the war.[67] Three new security zones have been established in Marib city district and neighboring Marib al-Wadi district.[68] Training courses have been held with the aim of improving the performance of police departments in the districts.

From 2015 to 2017, when Houthi forces targeted Marib, many explosive devices were planted in Marib city. One, in July 2016, killed seven people and wounded 18 in a crowded qat market in the capital.[69] Others went off at checkpoints and in the streets. Other crimes — gangs stealing vehicles, blocking highways and robbing people in the streets — made movement unsafe. The SSF installed surveillance cameras on main streets, set up new checkpoints along roads entering Marib city, and arrested criminal gangs and alleged Houthi bombmakers.

In November 2016, Governor Al-Aradah, who is also chairman of the security committee, appointed Colonel Abdel-Ghani Ali Abdullah Shaalan as the new SSF commander.[70] Shaalan, who is pro-Islah, has played a significant role in reorganizing the forces.[71] Shaalan previously served as chief of staff of the Central Security Forces in Marib. In 2015, he led Security Belt forces in Marib in the fight against the failed Houthi march toward Marib city.

Prior to the outbreak of war, there was only one trial court in Marib city. When the Houthis attempted to storm the city, most court employees fled. With a shortage of staff and lack of support from the Sana’a-based Ministry of Justice, Marib’s court suspended operations. The local authority helped restart the court’s operations, despite the fact that the central government’s Supreme Judicial Council is responsible for the budget and governance of the judiciary.[72]

The local authority also provided judges with housing and a judicial complex, including a three-story building for prosecutors’ offices.[73] The Supreme Judicial Council has sent new judicial cadres to the courts and prosecution offices, and has coordinated with the government to disburse judges’ salaries from the central bank branch in Marib.[74]

On April 30, 2018, the Supreme Judicial Council transferred jurisdiction of the specialized criminal court in Sana’a, which had been taken over by Houthi authorities, to Marib city, where it fields cases from 10 governorates.[75] The following month, Al-Aradah pledged in a joint meeting with the judiciary and security services to continue building out these institutions.[76] At the meeting, the top judge in Marib, Aref al-Mikhlafi, said that his court was about three-fourths of the way through a backlog of nearly 400 criminal cases sent to it since 2017.

Additional markers of a functioning law enforcement system in the governorate in 2018 included the removal of arms markets in Marib city, the prohibition on firing of guns in the city and the seizure of large quantities of smuggled hashish, weapons, explosives and antiquities, according to a security official.[77] The same year, Marib received 225 western diplomats and journalists as part of various international delegations.[78]

The Last Government Stronghold in Northern Yemen

Local authorities in Marib gained more control over their own governance in the days after the Houthis put President Hadi under house arrest in Sana’a and forced him and his cabinet to resign on January 22, 2015. In doing so, Marib authorities had overstepped existing laws that limit the autonomy of local authorities, but the moves were made more agreeable by the governorate’s steady backing of Hadi and its willingness to host coalition forces in subsequent months. After Hadi fled house arrest and arrived in Aden on February 21, 2015, the local authority renewed its loyalty to him and the internationally recognized government.[79]

Prior to the Saudi-led coalition intervention in Yemen’s conflict, Al-Aradah led the efforts to defend Marib from a Houthi takeover; he lost a son in battle in August 2015.[80] Marib was the only governorate at the time that Houthi authorities were unable to control in the north.

Since the coalition intervened, Yemeni government forces and the Saudi-led coalition have used Marib as the headquarters for military operations against the Houthis in the north. Prince Fahd bin Turki, who was then the top Saudi military commander to Yemen as head of the coalition joint forces, officially visited the governorate on September 19, 2015 and met the governor and the army command.[81]

Two months later, then-Vice President and Prime Minister Khaled Bahah arrived in Marib. After meeting with Al-Aradah, Bahah announced that various ministers would carry out their jobs from Marib.[82] A government delegation headed by then-Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Civil Service Abdulaziz Jabbari arrived in April 2016. In July 2016, President Hadi, newly appointed Vice President Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar and a number of ministers touched down in Marib city, where they held a meeting with the local authority and military leaders.[83] It was Hadi’s first visit to the governorate since he assumed the presidency in 2012.

Since then, Hadi’s government has treated Marib like an unofficial capital in the north and a launching pad for military operations against the Houthis. By the end of 2016, the coalition-backed army had regained control of Al-Hazm city, the capital of Al-Jawf governorate, and most of the Nehm district in the northeast part of Sana’a governorate from the Houthis. Those military victories, combined with Marib’s growing importance as a political center, prompted further visits from an increasing number of Yemeni officials, most notably Al-Ahmar, who is the top commander of military operations in northern Yemen. Other top Yemen military officials based in Marib include Minister of Defense Lt. Gen. Mohammed Ali al-Maqdashi and Sagher bin Aziz, the chief of staff and commander of the joint operations. Marib is where the largest number of troops loyal to President Hadi are based in Yemen.[84]

A number of training camps and departments within Yemen’s Ministry of Defense are also based in Marib, as is the headquarters of the Third Military Region, which is responsible for operations in Marib and Shabwa governorates. Temporary headquarters of the Seventh Military Region, which oversees operations in four Houthi-controlled governorates – Sana’a, Dhamar, Ibb and Al-Bayda – is currently located in Marib.[85] The Sixth Military Region, which covers operations in Al-Jawf, Amran and Sa’ada, is also temporarily based in Marib.[86] The Saudi-led coalition’s main base in Marib is located in Tadaween camp, while coalition troops are stationed at various locations in the governorate, including at a joint operations center in Mass Camp.

In addition to national and coalition military bases, a number of central government institutions have opened offices in Marib. A branch for the Passports and Immigration Authority was opened in Marib for the first time, as well as the headquarters of the General Anti-Drug Administration. The Ministry of Interior opened an office in Marib to manage security in Marib, Al-Bayda and Al-Jawf. Some local authorities from the Houthi-controlled governorates of Sa’ada, Sana’a, Amran, Amanat al-Asimah and Al-Mahwit opened temporary headquarters in Marib, from which they attempt to administer affairs and coordinate services for their governorates under Houthi control, such as domestic gas supplies and salaries.[87]

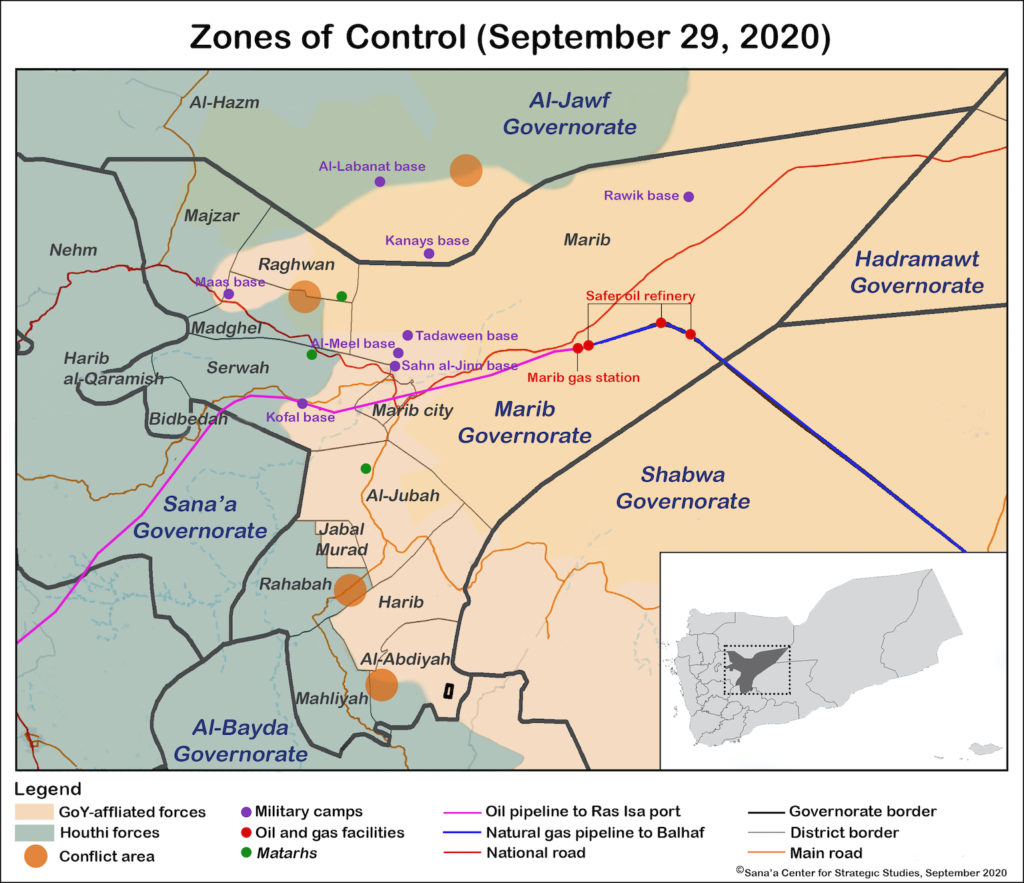

With the exception of the Serwah fronts, where clashes raged regularly with little progress for any party, Marib had witnessed relative stability since the initial confrontation with the Houthis at the end of 2015 until the beginning of 2020. Since January, Houthi forces have pushed relentlessly into the governorate, opening several new fronts that stretch from Marib’s northern border with Al-Jawf to its southern frontier with Al-Bayda. If the Houthis capture Marib, the government will lose what evolved through the war into one of the most important political and military centers inside the country. Saudi Arabia also stands to lose one of its most important areas of influence in Yemen, a region that represents a last line of defense against further Houthi encroachment toward the Saudi border. Two Yemeni government officials interviewed in August said the Houthis, after seizing Al-Hazm in late February, had threatened to revoke the truce on the borders and to resume airstrikes in Saudi Arabia if the kingdom continued to provide air support to government forces and tribes in the vicinity of Marib, terms which Riyadh refused.[88]

Houthis Launch Massive Ground Attack to Capture Marib

After nearly two years of stalemate along the battlefronts between the Houthi-held capital of Sana’a city and government-controlled Marib city, clashes erupted in mid-January 2020 in the mountainous Nehm district in northeastern Sana’a governorate as well as in neighboring districts in western Al-Jawf and Marib governorates.[89] In the preceding five months, these areas had fallen quiet as the Houthis and Saudi Arabia had been engaged in private negotiations and the government was preoccupied with STC advances in southern Yemen.[90] UN Special Envoy for Yemen Martin Griffiths told the UN Security Council in a briefing on January 16 that he was “witnessing one of the quietest periods of this conflict.”[91]

Two days later, a ballistic missile struck a government training camp in the Al-Mayl area northwest of Marib city, killing 111 soldiers and wounding dozens of others.[92] It was the largest loss of government forces in a single missile strike since the war began. The government-controlled Ministry of Defense in Marib blamed the Houthis for the attack and claimed it was an attempt to avenge the US assassination of Iran’s Quds force leader, Qassem Soleimani, in Baghdad in the first week of January.[93]

In conjunction with a flurry of missile strikes elsewhere in Marib, the Houthis launched massive ground attacks on government sites in Mount Haylan and Al-Mukhdarah in Marib’s western Serwah district. The aim of these attacks was to reach the main road connecting Marib and Sana’a, and cut off the supply route to government forces in Al-Jawf and Sana’a governorates. At the same time, Houthi authorities disconnected internet and phone networks in Al-Jawf.[94]

On January 24, Al-Maqdashi, the defense minister, met with Yemeni and coalition military commanders in Marib and announced a “tactical withdrawal” from the Nehm front.[95] As Nehm fell into Houthi hands in late January, Marib tribes issued an urgent call for the mobilization of armed fighters to support the army forces and stop the Houthis’ expansion into their lands.[96] The sudden setbacks were striking. All of the government forces’ progress in Nehm since 2016 had been lost in a week.

Marib’s governor, Al-Aradah, cut short a medical trip outside the country and returned to the governorate to prepare a response. In late January, Al-Aradah met with Marib’s security committee, tribal and political groups within the governorate, as well as the leadership of the Ministry of Defense and the coalition to mobilize and coordinate support for clashes with the Houthis.[97] Tribes gathered their weapons and readied fighters in locations known as al-matarh, which were formed after the Houthis took over Sana’a in 2014 and threatened to invade Marib. Al-Matarh are camps established by Marib’s tribes to mobilize fighters and store supplies for ongoing battles.[98] During fighting with the Houthis, these rallying points helped secure Marib’s borders and support the government forces.

By the end of January, the Houthis had achieved progress in the north of the governorate and had taken control of large parts of Majzar district and a number of sites in Mount Haylan. The military spokesperson for the Houthis announced that the group had seized a number of districts of Marib, reaching the western outskirts of Marib city.[99] A political leader of the Houthis, Mohammed al-Bukhaiti, said the group could take full control of Marib, but they stopped short of the capital due to what he called the mediation of an Arab state.[100]

Amid the setbacks faced by government forces, the tribes, some of whose members have enlisted in the army, have assumed a significant role in fighting the Houthis on four fronts. The Abidah tribe fought in the desert along the northern border with Al-Jawf; the Jahm in western Serwah district; the Jadaan in Marib’s northwest Majzar, Madghel and Raghwan districts; the Murad in Marib’s southern districts of Mahliyah and Rahabah; and the Bani Abd in southern Al-Abdiyah district.

As the Houthis pushed deeper into Al-Jawf, Marib’s local authority formed a joint operations room with the army and coalition leadership and tried to secure the governorate from Houthi sleeper cells and other internal threats that might affect battles on the front lines.

On February 19, Al-Maqdashi survived a landmine explosion that killed six of the defense minister’s companions on the Serwah front that separates Marib city from Nehm.[101] In the final days of February, the Houthis seized control of Al-Jawf’s Al-Ghayl and Al-Khalq districts, before taking control of most of the governorate’s capital, Al-Hazm.[102] Houthi fighters also managed to seize the army’s strategic Labnat camp in Al-Jawf’s neighboring Khabb wa Al-Sha’af district, as government forces and tribal fighters withdrew to areas east of Al-Hazm.

After the fall of Al-Jawf’s capital to the Houthis, all attention turned to Marib, as concerns about the possibility of the Houthis’ continued progress towards the governorate increased. The Hadi government in Riyadh had little to offer to halt Houthi advances into Marib, except to send a ministerial team headed by Minister of Local Administration Abdul Raqib Fateh, who was charged with supporting the army’s battle against the Houthis. Two days later, Vice President Al-Ahmar arrived in Marib city and met with Yemeni and coalition military leaders.[103]

In an attempt to ease the military escalation, the UN envoy flew to Marib city from Riyadh on March 7, marking his first visit to the governorate. At a press conference, Griffiths demanded the immediate and unconditional cessation of military activities, the resumption of the peace process and the preservation of Marib as a safe haven for refugees.[104] His arrival in Marib coincided with a major Houthi escalation in southern Al-Jawf, along the border with Marib. Houthi fighters pushed further into Al-Jawf’s Khabb wa Al-Sha’af district and briefly seized control of the army’s Al-Khanjar camp. Houthi attempts to storm Marib’s northern border continued for nearly two weeks, with the aim of cutting the international highway that connects Marib to eastern Al-Jawf, Hadramawt and the Al-Wadiah border crossing with Saudi Arabia. The highway also provides a key access point to Marib’s Safer oil refinery.[105] Tribal fighters east of Al-Hazm and in Al-Kanays Matarh (near a military base of the same name) managed to thwart the Houthi advances in ambushes and surprise attacks, taking advantage of their familiarity with the open desert landscape. Houthi fighters are generally more accustomed to operating in mountainous terrain. The flat desert also made Houthi fighters easier targets for coalition fighter jets.

After failing to advance into Marib’s northern Wadi Abidah and Raghwan districts from Al-Jawf, the Houthis launched a major offensive on several fronts in Marib’s mountainous Serwah district. On March 16, that front witnessed one of the fiercest confrontations since the start of the war as the Houthis pushed toward the strategic Kofel army base. Kofel is one of the largest camps of government forces and the last major line of defense for Marib city, which is visible from the camp about 40 kilometers to the east.[106]

In confrontations that lasted more than 15 consecutive hours, the Houthis reached the camp’s surroundings. Backed by coalition airstrikes, fighters from the Murad and Abidah and Jahm tribes joined government forces in countering the attacks.

On April 1, government forces backed by tribesmen took control of large parts of Serwah’s strategic Haylan mountain range, which overlooks Marib city from the northwest and acts as a natural barrier to the capital.[107] Houthi forces have used these highlands to launch Katyusha rockets against Marib city and surrounding military sites. Securing parts of Haylan marked the first victory for the army after a string of withdrawals and defeats in Nehm and Al-Jawf. The local authority and the tribes played a crucial role in this process.[108]

With fighting raging on several fronts in Marib, the coalition spokesman announced a comprehensive cease-fire for an initial period of two weeks, starting on April 9, in response to the UN secretary-general’s calls to lay down arms to confront the coronavirus.

Houthi spokesman Mohamed Abdel Salam rejected the cease-fire, calling it a political maneuver.[109] Fighting not only continued unabated, but intensified in some areas. From April 9 through May 23, when the ceasefire officially ended, coalition fighter jets had carried out at least 205 air raids, launching up to 789 individual airstrikes.[110] More than half of the airstrikes targeted two districts: Khabb wa Al-Sha’af in Al-Jawf and Majzar in Marib, where Houthi offensives were concentrated.[111]

Ground battles continued on most fronts in the vicinity of Marib, without any progress. On May 27, a ballistic missile targeted the headquarters of the Ministry of Defense during a meeting of army commanders at Sahn al-Jin camp in Marib city. Al-Maqdashi and his newly appointed Chief of Staff, Saghir bin Aziz, escaped, but seven soldiers, including the son of bin Aziz, were killed.[112]

As the Houthis pushed toward Marib city from the west and northwest, the Qanyah front along Marib’s southern border with Al-Bayda governorate was heating up. Signs of a coming battle in Al-Bayda’s Radman al-Awad district, which is adjacent to Marib’s Mahliyah district, emerged in late April, when a tribal sheikh and senior leader of the GPC party, Yasser al-Awadi, publicly criticized the Houthis for killing a local woman and demanded justice. Weeks of reported mediation efforts between the Al-Awad tribe and the Houthis failed to defuse the hostilities and by mid-June, the Houthis overran tribal forces and swiftly seized control of the district.[113] The sudden fall of Radman al-Awad into Houthi hands surprised observers and raised fears of further advances toward Marib. After days of battles, Houthi forces managed to cut a key supply line for government forces in Al-Bayda’s northern Qanyah area and control strategic positions overlooking its market.[114]

On June 22, the head of the GPC branch in Marib, Abdul Wahid al-Qibli Nimran, warned Marib’s Murad tribesmen that the Houthis were mobilizing to subdue the governorate and called for more fighters to support the army units and tribes there.[115] In the ensuing three months of battles, Houthi forces have taken control of the Qanyah area and all of Mahliyah district and continue to fight Murad tribesmen in Al-Rahaba and Al-Abdiyah districts. At the time of publication, the Houthi battle for Marib formed an arc from the deserts of Al-Jawf’s eastern Khabb wa Al-Sha’af district through Marib’s Al-Wadi, Majzar and Serwah districts, down to Marib’s southern border with Al-Bayda governorate. Houthi fighters were trying to reach Al-Kanais base on the border of Marib and Al-Jawf and Marib’s Rawik military base north of the Safer oil refinery.

Conclusion

Oil-rich Marib governorate has transformed from a remote region long neglected by the state to a relatively stable and prosperous government stronghold. After confronting the Houthis and expelling them from most areas in the governorate in 2015, relative calm prevailed until 2020, unlike the ongoing state of conflict and crisis that ravaged so much of the country. This has allowed Marib to achieve a variety of successes that are absent in many other governorates. On the local and economic level, Marib has presented a successful model of local governance, enjoying a degree of autonomy and power in decision-making that most governorates do not have and that stands in stark contrast to the state’s usual excessive centralization. Securing revenues from its oil and gas resources has been key to helping Marib expand government services and rebuild and reactivate state institutions, most notably the security and judicial agencies, to provide greater security and resolve internal disputes. Politically and socially, the general consensus among Marib’s population has empowered the local authority and allowed the central government to use Marib city as a second capital to run its affairs in the north and launch military operations. All of these factors have made Marib a destination for millions of displaced people from various regions of Yemen affected by the war.

The most serious threat to Marib is the ongoing Houthi military advances into the governorate. Since the beginning of this year, the Houthis have stepped up their missile and ground attacks in an unprecedented way. The fall of Nehm, Al-Hazm and Radman al-Awad in 2020 have made Marib increasingly vulnerable to Houthi attacks from the north, west and south, respectively. If the Houthis reach Marib city and its environs, fighting could unleash a new humanitarian catastrophe, given that the governorate is home to more than 2 million displaced people and there are only two main highways on which they could flee. A conflict in and around Marib city could also impact heritage sites and nearby oil installations, sending ripple effects throughout the country given their role as the sole domestic source of cooking gas for all regions of Yemen. Marib stands both as the internationally recognized government’s last northern stronghold from which Yemen’s capital Sana’a can be retaken and as a wall to block Houthi advances toward oil-rich Hadramawt and Shabwa governorates.

This paper was produced by the Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies with the Oxford Research Group, as part of Reshaping the Process: Yemen program.

The Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies is an independent think-tank that seeks to foster change through knowledge production with a focus on Yemen and the surrounding region. The Center’s publications and programs, offered in both Arabic and English, cover political, social, economic and security related developments, aiming to impact policy locally, regionally, and internationally.

Oxford Research Group (ORG) is an independent organization that has been influential for nearly four decades in pioneering new, more strategic approaches to security and peacebuilding. Founded in 1982, ORG continues to pursue cutting-edge research and advocacy in the United Kingdom and abroad while managing innovative peacebuilding projects in several Middle Eastern countries.

Endnotes

- The other urban center in Marib governorate is Harib town, south of Marib city near the border of Shabwa governorate.

- Interview with Saif Muthana, head of the executive unit for IDP camps in Marib, August 2020.

- The International Organization for Migration’s most recent figures, from November 2018, put Marib’s IDP population at 739,458, of which 577,854 were living in Marib city. See “DTM Yemen,” International Organization for Migration, accessed September 24, 2020, https://displacement.iom.int/yemen. Local officials in Marib, including Muthana, estimate the overall figure at about 2 million.

- “Marib [AR],” Yemen Embassy in Saudi Arabia, https://www.yemenembassy-sa.org/Pages/%D9%85%D8%A3%D8%B1%D8%A8

- “Profile of Marib Governorate [AR],” National Information Center, https://yemen-nic.info/gover/mareb/brife/.

- Wadhah al-Awlaqi, Maged al-Madhaji, “Challenges for Yemen’s Local Governance amid Conflict,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, July 29, 2018, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/6314#_ftn25

- This includes the Marib Gas Station, which meets most of Yemen’s domestic gas needs, and the Safer oil refinery, which meets most of Marib’s petrol demand. As such, Marib has largely escaped the fuel shortages experienced in other governorates during the ongoing conflict. “Local Visions for Peace in Marib,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 1, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/7903

- The Al-Ashraf group follows the Shafei branch of Sunni Islam. “Unlike the Zaydis, who are not mainstream Shi‘i, Shafeis adhere to normative Sunni beliefs. In Yemen, they live in the mid- and lowlands and basically surround the Zaydi areas on the west coast up to the Saudi border and east into al-Jawf and Mareb.” Helen Lackner, Yemen in Crisis: Road to war, (London: Verso, 2019), 123.

- “Tribes in Marib sign an agreement to address any attacks on their lands [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, September 6, 2014, https://mail.almasdaronline.info/articles/117115; Marib governorate, “Local authority and Marib sheikhs sign agreement sponsored by a parliamentary committee to consolidate security in the governorate [AR],” Facebook, December 10, 2014, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=413855835433164&id=146991418786275

- Most of the tribes of Marib, along with the al-Ashraf group, are Shafei Sunni except Bani Jabr and its Jahm sub-tribe, which are Zaydi Shia.

- Hugh Naylor, “Yemen’s tribal confederations”, The National, February 27, 2012, https://www.thenational.ae/world/mena/yemen-s-tribal-confederations-1.391643; Abdul Aziz Qaid al-Masoudi, Contemporary Yemen from the tribe to the state: 1911 – 1967 [AR], (ktab INC., 2006), pgs. 137-39.

- Brigades were administrative divisions used by the Mutawakkilite Kingdom and later by the Yemen Arab Republic until they were replaced with governorates in 1998. Ismail Al-Akwa’e, Makhalef al-Yemen, (Al-Jeel al-Jadeed, 2008-2009), pgs. 71, 73, 77, 90-91; Interview with a local official in August 2020.

- “Marib glories and the capital of civilization and dams [AR],” Al-Thawra, November 20, 2014, http://althawrah.ye/archives/102111

- The area had already begun to be sidelined around 100 A.D. when sea routes overtook overland trade. Charles Schmitz, Robert D. Burrowes, Historical Dictionary of Yemen, (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 395.

- Bilal al-Tayeb, “Marib…a history of rejection [AR],” Al-Asimah Online, June 26, 2020, https://alasimahonline.com/art_writings/1140#.X2EHLCUieaM

- Interviews with two tribal leaders in August 2020.

- “The crown prince and Yemen’s Prime Minister chair the meeting of the Saudi-Yemeni Coordination Council [AR],” Al-Riyadh, November 24, 2007, http://www.alriyadh.com/293955

- Adel al-Ahmadi, ”Saudi Arabia warns the Yemeni president: Marib is a red line [AR],” The New Arab, January 17, 2015, ibit.ly/1o5W

- Interview with a local official on August 5, 2020.

- Ibid.

- Interview with a local official in Marib on August 6,2020; “Abu Dhabi Fund for Arab Economic Development, Annual Report,1985-1986,” https://www.adfd.ae/Lists/PublicationsDocuments/Annual-Report-1985-1986.pdf

- Interviews with tribal leaders in August 2020.

- Ibid.

- Interview with a local official in August 2020; “In pictures, sons of king of Bahrain and son of the ruler of Dubai participate with coalition forces in Marib [AR],” Akhbar 24, October 7, 2015, https://akhbaar24.argaam.com/article/detail/239238; ”In pictures … the son of the ruler of Dubai publishes footage during his participation with coalition forces in Yemen and the liberation of ‘Bilqis’ throne [AR,]” CNN Arabic, October 9, 2015, https://arabic.cnn.com/middleeast/2015/10/09/yemen-mansoor-bin-mohammed

- Political parties have been known to exploit conflict over land and revenge killings for partisan agendas. In Marib, Al-Jawf and Al-Bayda, competition during elections for local council seats has triggered some tribal conflicts. Nadwa Al-Dawsari, Daniela Kolarova, Jennifer Pedersen, “Conflicts and Tensions in Tribal Areas in Yemen,” Partners Yemen and Partners for Democratic Change International, 2011, https://partnersbg.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2011-Yemen-Conflict-Assessment-.pdf; Sarah Phillips, Yemen’s democracy experiment in regional perspective: Patronage and pluralized authoritarianism, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan 2008), 93-94.

- Nadwa Al-Dawsari, Daniela Kolarova, Jennifer Pedersen, “Conflicts and Tensions in Tribal Areas in Yemen,” Partners Yemen and Partners for Democratic Change International, 2011, https://partnersbg.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2011-Yemen-Conflict-Assessment-.pdf

- Ibid.

- Adel Mujahid al-Sharjabi, “The province of Sheba: a jewel in the hands of a coal miner [AR],” Assafir Arabi, July 30, 2014, ibit.ly/nGWF; “Local authority in Marib Governorate [AR],” National Information Center, https://yemen-nic.info/gover/mareb/politlocal/

- Ibid.

- Nadwa al-Dawsari, “Marib Youth and Political Transition in Yemen,” Atlantic Council, March 31, 2014, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/marib-youth-and-political-transition-in-yemen/

- Andrew McGregor, “Tribal Resistance and al-Qaeda: Suspected U.S. Airstrike Ignites Tribes in Yemen’s Ma’rib Governorate”, The Jamestown Foundation, July 16, 2010, https://jamestown.org/program/tribal-resistance-and-al-qaeda-suspected-u-s-airstrike-ignites-tribes-in-yemens-marib-governorate/; Fahd al-Tawel, “The local authority wonders about the incident [AR],” Facebook, May 25, 2010, https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=123697214319983&id=100000589470364; “Al-Shabwani’s father rejects presidential arbitration and demands the extradition of those behind the operation [AR],” Al-Thawra Net, May 25, 2010, https://althawra-news.net/news101825.html

- Interviews with two tribal leaders, one from Jahm and the other from Abidah, in August 2020.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Waleed al-Rajehi, “Marib .. Achievements despite challenges [AR],” Mareb Press, January 13, 2013, https://marebpress.net/news_details.php?lng=arabic&sid=50991

- “The governor of Marib succeeds in signing a tribal document to protect the transmission towers, and pledges not to repeat the attacks on them [AR],” Mareb Press, May 6, 2012, https://marebpress.net/news_details.php?lng=arabic&sid=43229

- Waleed al-Rajehi,”Marib .. Achievements despite challenges,” Mareb Press, January 13, 2013, https://marebpress.net/news_details.php?lng=arabic&sid=50991

- “A reluctant refuge for al-Qaeda”, The Economist, July 27, 2013, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2013/07/27/a-reluctant-refuge-for-al-qaeda; Ahmad al-Wali, “The government’s response to the saboteurs’ demands encourages them to continue blowing up the oil pipeline and electricity pylons [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, September 14, 2013, https://almasdaronline.com/article/49946

- Interviews with two Murad tribesmen, one of them affiliated with GPC, in August 2020.

- “Speech of Mr. Abdul Malik Badr Al-Din Al-Houthi in the Prophet’s Birthday 2015 [AR],” YouTube, January 3, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CIqFqgLOE6Q; “Al Houthi threatens to invade Marib to prevent it from being handed over to Al Qaeda [AR],” Al-Jazeera, January 3, 2015, ibit.ly/HKJA

- “Ghalib Abdullah al-Zaidi,” UN Security Council, February 22, 2017,

- Ahmed al-Haj, “Yemen tribal leaders say senior al-Qaida leader killed,” The Associated Press, August 25, 2018, https://apnews.com/cd2949fab642470294aaedde24ca4630/Yemen-tribal-leaders-say-senior-al-Qaida-leader-killed

- Interview with Marib’s Director of Information, Statistics and Documentation Department, Abdurabu Hulais, August 5, 2020.

- “Official in the local authority in Marib: More than a million people were displaced due to the war in the governorate [AR],” Yemen Shabab, June 28, 2016, https://yemenshabab.net/edithome/3191

- Interview with Saif Muthana, Head of the Executive Unit for IDP camps in Marib, August 2020.

- This figure was calculated based on an assumed 2.72 percent annual increase in the population since the last official census was conducted in 2004, which put Marib city’s population at about 48,300. “Profile of Marib Governorate [AR],” National Information Center, https://yemen-nic.info/gover/mareb/brife/

- “Rising rents are compounding Yemenis’ suffering,” Al-Masdar Online English, January 7, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/238

- Interview with Saif Muthana, head of the executive unit for IDP camps in Marib, August 2020.

- “Deputy Governor Moftah discusses with the international migration the situation of the displaced [AR],” Marib governorate local authority, March 18, 2019, https://marib-gov.com/news_details.php?lng=arabic&sid=1396

- Interview with Saif Muthana, head of the executive unit for IDP camps in Marib, August 2020.

- Interviews with four native residents of Marib city, June 2020.

- “Local Visions for Peace in Marib,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 1, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/7903

- ِAbdullah al-Qadri,”Marib’s leaders authorize local authorities to implement only the directions of the governor and the commander of the Third Military Region [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, January 24, 2015, https://almasdaronline.com/article/67012

- “The governor of Marib announces the suspension of oil and gas revenues to the Sana’a Central Bank account [AR],” Belqees TV, November 22, 2015, ibit.ly/tjq4

- Interview with an official in Marib’s local authority, August 5, 2020.

- “President Hadi directs the allocation of 20 percent of oil and gas revenues for the benefit of development in Marib [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, November 16, 2016, https://almasdaronline.com/article/86385. Marib was connected to the central bank’s Aden branch in June 2019. “The success of the process of linking the branch of the Central Bank in Marib and its general administration in Aden,” Economic Committee, June 16, 2019, https://ecyemen.com/announcements/996/

- Ibid.;”The Prime Minister reveals the revenues of Marib, and how they are spent? [AR],” Al Khabar Post, June 14, 2019, https://www.alkhabarpost.com/news/222

- “Al-Aradah directs to boost each directorate’s account with 100 million to face the flood disaster [AR],” Saba Net, August 7, 2020, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/65034

- Ali al-Oqabi, Ali al-Sakani, “Breaking stereotypes, women from Marib are attending university in record numbers,” Al-Masdar Online English, March 6, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/430; “Local Visions for Peace in Marib,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, August 1, 2019, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/main-publications/7903; “Governor Al-Arada inspects work on the completion of the first Olympic football stadium in Marib [AR],” Marib Governorate, August 7, 2019, http://marib-gov.com/news_details.php?sid=1720

- It costs 3,700 Yemeni rials for 20 liters of petrol, and 2,200 rials for a single gas cylinder of cooking gas at official prices.

- “Recent study: Marib is a young society frustrated by the governorate’s development,” Saba Net, April 1, 2010, https://www.saba.ye/ar/news210375.htm

- While figures for the first years of the arrangement were not available, based on a balance sheet from January to November 2018, Marib’s 20 percent share of oil and gas revenues during this period would have been approximately US$37 million. “Letter dated 25 January 2019 from the Panel of Experts on Yemen addressed to the President of the Security Council,” UN Security Council, January 25, 2019, Annex 23, p. 146, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/1664359?ln=en

- Outside of Marib city, the Special Security Forces also have checkpoints along the roads connecting Marib with Sana’a, Al-Bayda and Al-Jawf governorates.

- “The police department graduated its first class of female officers [AR],” Al-Khaleej Newspaper, March 3, 10, 2017, http://www.alkhaleej.ae/alkhaleej/page/57f37e9e-57cc-46ab-a6e9-c8ce7a15ff3f#sthash.AUO8afWp.dpuf

- “Police department receives 23 cars [AR],” Akhbar Alyom, October 23, 2017, https://akhbaralyom-ye.net/news_details.php?sid=99923; “Governor Al-Aradah provides the military police number of military pickups to enhance its capabilities [AR],” Marib Governorate, April 19,2018,

- The four new police stations are located in the following neighborhoods in Marib city: Al-Rawdha, Al-Matar, Al-Salam and Al-Sharaka. The existing police station is located downtown.

- Interviews with a local authority official and a security official in Marib, August 2020.

- “Bomb explodes at qat market in Yemeni oasis city,” Al Araby, July 27, 2016, https://english.alaraby.co.uk/english/news/2016/7/27/bomb-explodes-at-qat-market-in-yemeni-oasis-city

- Marib’s security committee, which is led by Al-Aradah, includes leadership of the Third Military Region (Defense Ministry), the police department (Interior Ministry) and the Political Security Organization (intelligence services); “Marib Governor appoints new commander of security forces in Marib [AR],” Al-Mawqea Post, November 20, 2016, https://almawqeapost.net/news/13856

- “Marib police conclude two training courses for security personnel,” Marib Governorate, October 11, 2019, https://marib-gov.com/news_details.php?sid=1866&lng=english

- Moad Rajeh and Wadea al-Asbahi,”Despite the human and material difficulties and obstacles, Marib … the judiciary is restoring its justice [AR],” Akhbar Alyom, December 5, 2018, https://akhbaralyom-ye.net/news_details.php?sid=106865

- Interviews with local officials on July 26, 2020; ”Chief Prosecutor of the Court of Appeal in Marib receives new prosecution building, and Al-Aradah reaffirms the need to reactivate the judicial and security services in the governorate [AR],” Marib Press, October 21, 2017, https://marebpress.org/news_details.php?sid=131725

- Interviews with local officials on 26 July, 2020.

- “A judicial decision to transfer the jurisdiction of the specialized criminal court in Sana’a to the newly-established court in Marib [AR],” Al-Mawqea Post, April 30, 2018, https://almawqeapost.net/news/30228

- “The governor of Marib chairs a joint meeting of the judiciary and security agencies in Marib [AR],” Saba News Agency, May 15, 2018, https://www.sabanew.net/viewstory/33181

- Interview with an official in the Marib police department in August 2020; Fouad al-Alawi, “Marib Police..From consolidating security to protecting history and the national economy [AR],” Marib Governorate, November 15, 2018, https://marib-gov.com/news_details.php?lng=arabic&sid=1103

- “Marib welcomes 225 foreign diplomats and media professionals in 2018 [AR],” Marib Governorate, March 31, 2019, https://marib-gov.com/news_details.php?sid=1425

- “The local authority in Marib confirms its adherence to the legitimacy of President Hadi [AR],” Mareb Press, February 25, 2015, https://marebpress.net/news_details.php?sid=107522

- “The son of Marib Governor died of wounds sustained during confrontations with the Houthi and Saleh militias [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, August 22, 2015, https://mail.almasdaronline.info/articles/129937/amp

- “The commander of the Saudi ground forces arrives in Marib, in preparation for the decisive battle [AR],” Mareb Press, September 18, 2015, https://marebpress.org/news_details.php?sid=112682

- “Bahah promises to visit Sanaa soon and says that ministers in his government will work from Marib, and Arada welcomes [AR]”, Mareb Press, November 22,2015, https://marebpress.com/news_details.php?lng=arabic&sid=114365

- “President Hadi arrives in Marib and affirms that will not return to Kuwait’s consultations if the UN attempts to impose its latest vision [AR],” Presidency, July 10, 2016, https://presidenthadi-gov-ye.info/ar/archives/

- Maged al-Madhaji, “The Battle of Marib: Houthis Threaten Yemeni Government Stronghold,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 10, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/9679

- After the war started, it was moved to Marib until 2018 before being relocated to Nehm until the beginning of 2020.

- Interview with an official in the Ministry of Defense on August 7, 2020.

- Interviews with local authorities in Marib on August 6, 2020.

- Interviews with a Yemeni government official in Riyadh and an official in the Defense Ministry in Marib in August 2020.

- “Analysis: ‘Unprecedented’ escalation east of Sana’a signals potential shift in Yemen war,” Almasdar Online English, February 5, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/308

- After STC-aligned forces seized control of Aden in August 2019, they pushed into Abyan and Shabwa governorates. When the pro-STC Shabwani Elite advanced toward Shabwa’s capital Ataq, the government deployed Marib-based troops who drove the STC forces from Shabwa.

- “Briefing of the special envoy to the UN secretary-general for Yemen to the open session of the UN security council,” Office of the special envoy for Yemen, January 16, 2020, https://osesgy.unmissions.org/briefing-special-envoy-united-nations-secretary-general-yemen-open-session-un-security-council-0

- “Death toll from Marib attack surpasses 110, overwhelms local hospitals,” Almasdar Online English, January 20, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/266

- “The Ministry of Defense calls troops to be on high alert, saying that Marib attack is an attempt by the Houthis to avenge the killing of Soleimani [AR],” Almasdar Online, January 19, 2020, https://almasdaronline.info/articles/176626

- Casey Coombs, “In the battles for Al-Jawf and Marib, Houthis weaponize Sana’a-based telecom companies,” Almasdar Online English, April 29, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/716

- “Yemen army commanders discuss ‘tactical withdrawal’ from Nehm front amid fierce clashes,” Almasdar Online English, January 24, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/281

- The call for tribal mobilization is known as “Nakaf”; “The tribes of Marib declare al-Nakaf .. Large tribal reinforcements for the National Army in the Nehm front [AR],” Al-Mashhad Al-Yemeni, January 23, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vTg99rIRxso

- “A security meeting in Marib stresses raising security preparedness and vigilance to confront the Houthis [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, January 25, 2020, https://almasdaronline.info/articles/176813

- Nakhla and Sehail areas in northern Marib were the first matarh established by the tribes in the governorate at the end of 2014. Later, the tribes established a new matarh of Al-Washah area in Al-Jawba district in southern Marib, under the leadership of Sheikh Abdul Wahid al-Qibli, head of the GPC branch in Marib.

- “Saree: Operation “Al-Bonyan Al-Marsous” liberates all Nehm areas [AR],” Al-Mayadeen, January 29, 2020, https://www.almayadeen.net/news/politics/1377114

- “Muhammad Al-Bukhaiti: We can fully control Marib. We stopped entering the city due to the mediation of an Arab country,” The Yemeni Messenger, January 31, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJR8TRpVVPg

- “Defense Minister Al-Maqdashi survived and six of his escorts were killed due to a landmine explosion in Serwah front [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, February 19, 2020, https://almasdaronline.info/articles/177829

- “Houthis advance into Al-Hazm, the governorate capital of Al-Jawf,” Al-Masdar Online English, March 1, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/407

- “VP discusses the military situation with the Minister of Defense, Chief of Staff, and the governors of Marib and Al-Jawf [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, March 6, 2020, https://almasdaronline.info/articles/178581

- “Yemen: UN envoy calls for ‘immediate and unconditional’ freeze on military activities,” UN News, March 7, 2020, https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/03/1058921

- ‘Maged al-Madhaji, “The Battle of Marib: Houthis Threaten Yemeni Government Stronghold,” Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, April 10, 2020, https://sanaacenter.org/publications/analysis/9679

- Adnan al-Jabrani, “While welcoming calls for a ceasefire, Houthis escalate attacks in Marib,” Al-Masdar Online, March 28,2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/543; “Yemen army repels Houthi attacks in Marib, Al-Bayda [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, March 19, 2020, https://al-masdaronline.net/national/489;

- “Government forces are making important progress in Serwah Mountains, west of Marib, after fierce battles with Houthi fighters [AR],” Al-Masdar Online, April 1, 2020, https://almasdaronline.info/articles/179910

- The local authority was responsible for general mobilization, overseeing tribal support, intensification of official, political and tribal meetings and coming up with a unified vision that resulted in the establishment of a number of tribal matarh. Local officials also renewed reconciliation agreements related to tribal disputes, the most prominent of which is the reconciliation between Al-Ghanem of the Murad tribe and Al-Janah of the Bani Abd tribe, in order to devote time to confronting the Houthis. Interview with a local official on August 5, 2020.

- “A Yemeni journalist to “Tasnim”: Saudi Arabia’s tactic to prevent the fall of Marib / Ansar Allah’s comprehensive vision for resolving the Yemeni crisis [AR],” Tasnim News, March 15,2020, t.ly/KU3h; ‘’The coalition truce in Yemen..The Houthis accuse Saudi Arabia of maneuvering and continuing the war [AR],” Al-Jazeera Net, March 9, 2020, ibit.ly/KayM

- “Air Raids Average at Least 5 Per Day During Yemen Ceasefire,” Yemen Data Project, May 2020,

- The airstrikes in Majzar were aimed at preventing Houthis from reaching the army’s strategic Mass camp.