FDA Proposes New Limits for Lead in Baby Foods

It’s an encouraging first step, experts say, but more action and stricter limits are needed

The Food and Drug Administration on Tuesday proposed new guidelines to lower the levels of lead found in certain packaged baby foods meant to be eaten by children under age 2.

Lead and other heavy metals can have a serious health impact, especially on babies and developing children. In kids, exposure to dietary heavy metals has been linked to attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, behavior problems, and lowered IQ.

The guidelines would set action levels of 10 parts per billion (ppb) for lead in fruits; most vegetables; mixed meals, including grain and meat-based mixtures; yogurts; custards and puddings; and meats.

The proposed levels are higher, 20 ppb, for dry cereals and single-ingredient root vegetables such as carrots, sweet potatoes, or beets. Root vegetables grow underground, and therefore may absorb more lead from the soil than other vegetables.

Heavy Metals in Baby Food

The presence of lead and other heavy metals in baby food is a persistent problem that has drawn increased scrutiny in recent years. Heavy metals naturally occur in the environment. But most of the levels in food come from water and soil that have been contaminated through industrial manufacturing, farming, or pollution, such as the use of leaded gasoline.

In 2018, CR’s tests of 50 different packaged foods for babies and toddlers found that two-thirds of products had concerning levels of lead, cadmium, or inorganic arsenic. Testing by other organizations has found similar problems.

In 2021, a Congressional subcommittee released two reports that revealed just how high levels of certain heavy metals were in baby food products and ingredients used to make those products, based on data submitted by baby food manufacturers.

One of those reports showed that 20 percent of baby foods tested by the baby food manufacturer Nurture contained more than 10 ppb lead, and the other showed that more than half of Plum Organics products contained more than 5 ppb lead. In addition, many ingredients used by manufacturers Beech-Nut, Hain, and Gerber contained more than 20 ppb lead.

That same year, the FDA announced its Closer to Zero action plan, which set the agency’s timeline for proposing limits on heavy metals in baby food—though according to that schedule, lead limits should have been out almost a year ago.

What the New Lead Limits Do and Don’t Achieve

The proposed limits of 10 ppb in many baby foods are stricter than European limits of 20 ppb, says Neltner, at the Environmental Defense Fund.

“I think we could go lower,” he says, but he adds that many labs would need to improve their testing capabilities to reliably test foods to lower numbers.

Still, in some cases “it appears the proposed standards were based more on current industry feasibility to achieve the limits, and not solely on the levels that would be optimal for protecting public health,” says CR’s Ronholm. In CR’s 2018 tests, 80 percent of the baby foods had lead levels below 10 ppb, showing that many manufacturers can achieve lower levels.

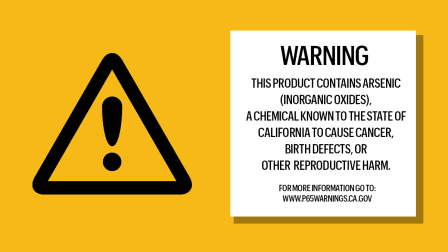

These action levels still need to be finalized. And in the meantime, health advocates are also waiting for the agency to set limits for arsenic, cadmium, and mercury in other foods. Right now, the only other limit the FDA has for baby food is 100 ppb for inorganic arsenic in rice cereal.

And while experts say there are a number of things parents can do to limit exposure to heavy metals for kids—including feeding them a wide variety of healthy foods, going easy on chocolate, and limiting fruit juice—one step that may be less helpful than parents hope is making homemade baby food. Previous research by the group Healthy Babies Bright Futures has found that homemade baby food typically has levels of heavy metals that are comparable with the levels in store-bought baby foods.

For that reason, the FDA and the Department of Agriculture need to take steps to invest in science on lowering levels of heavy metals in all crops, Neltner says.

CR’s experts agree. “We look forward to working with the FDA to build on this proposal and gradually lower and eventually eliminate toxic heavy metals in baby food,” Ronholm says.