Unfair share: Memphis communities call for environmental justice

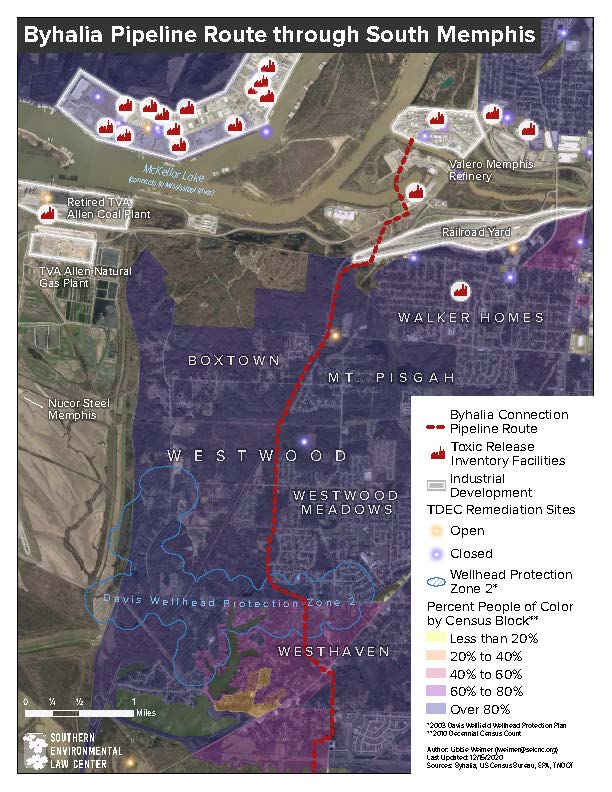

A long history of environmental injustice in South Memphis came to national attention when a predominantly Black community went to bat against the Byhalia Pipeline, a crude oil pipeline that could have endangered the drinking water source of a million Memphians and continued this unjust pattern.

And though Valero Energy Corporation and Plains All American Pipeline, L.P. formally cancelled the project July 3, community activists continue to shed light on what it’s like to live in a place surrounded by industrial pollution.

“They’re trying to lynch us in a different way—one that can just as much take our breath away,” said Justin J. Pearson, co-founder of Memphis Community Against Pollution, of pipeline developers and other big polluters. Pearson’s family has deep roots in the area and has experienced the influx of toxic industries over the years.

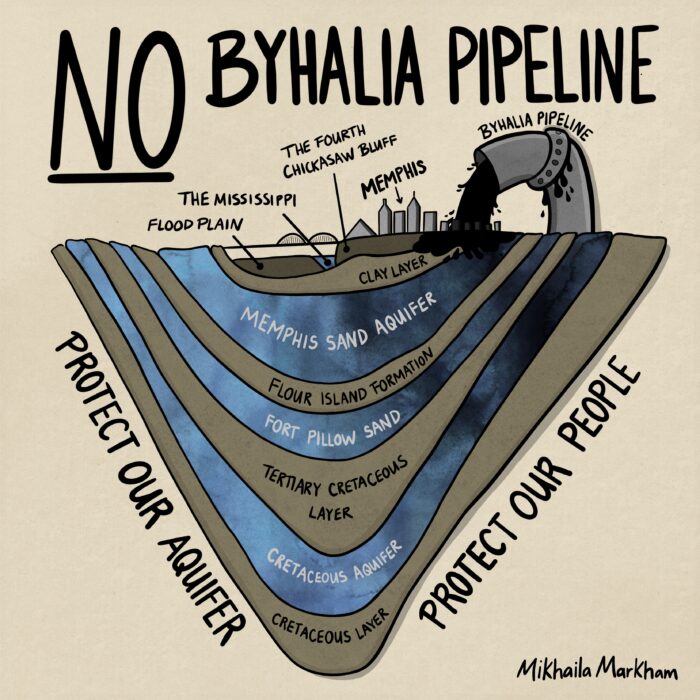

The latest proposal, the 49-mile, high pressure, Byhalia crude oil pipeline, would have created a second connection between two existing pipelines to transport oil through southern Memphis—crossing the city well where water is drawn up from an underground aquifer into predominantly Black communities—and down to the Gulf Coast, primarily for export. Because crude oil is known to contain cancer-causing hazardous chemicals like benzene, Memphis-area residents would be at risk when the pipeline leaked or spilled.

The risk is even greater because new research shows breaches already exist in the underground clay layer that serves as a natural barrier between pollution and the drinking water aquifer. Just one pound of crude oil can contaminate 25 million gallons of groundwater, or enough to fill almost 40 Olympic-sized swimming pools.

City officials are considering instituting their own aquifer protections, which are currently scheduled to be voted on in fall 2021.

OVERBURDENED

Pipeline developers seemed to be following a playbook for environmental racism, targeting a Black neighborhood they assumed lacked the political power of wealthier areas of Memphis. The move drew widespread backlash, in no small part because of the repeated pattern of pointing polluting industries to this part of town.

Even international newspaper The Guardian called the Byhalia Pipeline and the attention it garnered a “flashpoint” in the intensifying conversation around environmental justice.

This area of southwest Memphis has a rich history—a key chapter starting when Boxtown was settled by formerly enslaved men and women after the Civil War. The name comes from the number of early homes fashioned from parts used from boxcars on the nearby railway.

Pearson described it like this in Action Planet: Meeting the Climate Challenge, a NowThis special with Vice President Kamala Harris that aired this Earth Day.

“We would go to our grandmother’s house every Sunday after church,” he said. “You drive up off the exit and there are these pillows of smoke and as a kid I was fascinated by them. And it wasn’t until relatively recently, I would say, that I began to understand the folks who are breathing that air, that’s us.”

He continued, “What we get to greet us is not a ‘Welcome to Southwest Memphis’ sign. What we get are these toxins, these billows of smoke and toxins that are literally killing us.”

Here, residents are 97% Black and nearly half of the households have an income below $25,000 a year.

For decades, the City of Memphis refused to incorporate Boxtown or provide basic infrastructure like water and sewer service despite the strong neighborhoods forming. Instead, the city and state governments allowed polluting factories to concentrate in the area.

“Now there are dozens of polluting facilities like a ring around the community,” says Amanda Garcia, Managing Attorney in SELC’s Tennessee office. She and Attorney George Nolan have led SELC’s work to protect these communities’ right to clean air and water.

Ironically, many industries are drawn to Memphis for its underground aquifer and the high quality water it provides. Yet what was once a pastoral stretch along the banks of Mississippi River quickly succumbed to industries looking to take advantage of water access, like the Valero Oil Refinery built in the1950s, a steel mill, a wastewater treatment system, and Tennessee Valley Authority’s Allen Plant, which burned coal until recently. A nearby military base is now a Superfund site, as is a former drycleaners.

An unlined coal ash pit at Plant Allen has already highly contaminated the surrounding groundwater with arsenic and other pollutants. Some water samples taken nearby contain the carcinogen at nearly 400 times the safe drinking water level.

“And the list goes on,” says Garcia, adding that the large number of polluting facilities have resulted in a cancer rate four times higher than the national average in Southwest Memphis. The area also has high asthma rates, has been deemed a hotspot for air pollution, and has received a failing grade in terms of air quality from the American Lung Association.

“On one level when we talk about an overburdened community, we’re talking about the sheer number of polluting sources located there, but on a more personal level, we’re talking about the burdens of loss and poor health that members of the Southwest Memphis community have already borne,” adds Garcia. “We’re talking about peoples’ lives being cut short.”

SELC has long recognized that, while environmental harm hurts everyone, communities of color face a disproportionate burden of that harm.

Chandra Taylor, Leader of SELC’s Environmental Justice Initative

A severe winter storm this February illustrated once again that pollution and poor infrastructure don’t mix. At the same time a boil water advisory was announced as drinking water pumps and pipes failed, the Valero refinery adjacent to Boxtown rained pollution from a toxic flare onto the community and sullied nearby Nonconnah Creek.

For reasons like this and more, in a letter to President Joe Biden’s White House Environmental Justice Advisory Committee, Senior Attorney Chandra Taylor said South Memphis is exactly the type of place deserving of a boost from the president’s Justice 40 Initiative, which would order that a portion of federal investments “flow to disadvantaged communities.”

Those investments would focus on clean drinking water infrastructure, clean energy and transit, sustainable housing and workforce development, and helping to clean up generations of pollution.

“SELC has long recognized that, while environmental harm hurts everyone, communities of color face a disproportionate burden of that harm,” says Taylor, leader of the organization’s Environmental Justice Initiative. “And we know that historic legal discrimination, market forces, zoning, and a lack of political power are just a few of the underlying reasons. We’re pushing to see this reparative federal action through.”

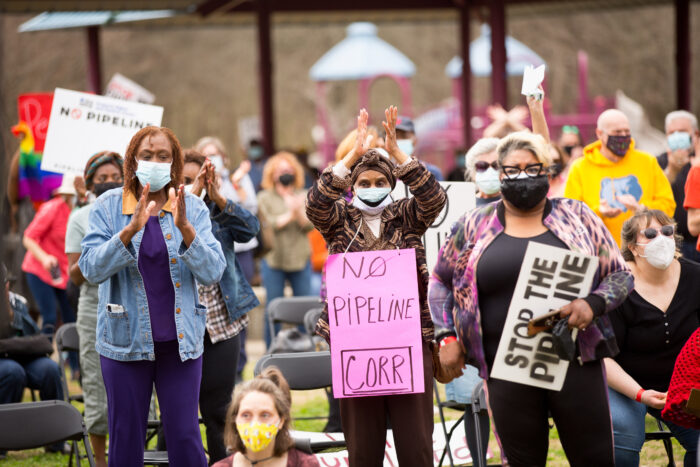

PEOPLE POWER

From the start, Byhalia project developers have drawn the community’s ire, first for calling the latest proposed route the “point of least resistance,” and then for invoking the power of eminent domain to take private property for a corporate project with questionable public benefit.

“Plains has said they’ve been transparent about this process—they have not,” says Kathy Robinson, a fourth generation resident of Southwest Memphis and a co-founder of Memphis Community Against Pollution. “We have residents who would have this pipeline built on the side of their homes, and they know nothing about this project.”

The company’s approach quickly compelled Robinson, Pearson, and third MCAP co-founder Kizzy Jones to organize against the pipeline project dubbed a “reckless, racist ripoff” by former Vice President Al Gore, founder of the Climate Reality Project.

As a result of their activism, not only were neighbors informed about the potential impact of the pipeline in their communities, but other high profile celebrities and leaders including Mark Ruffalo, Justin Timberlake, and Rev. Dr. William Barber II of the Poor People’s Campaign engaged publicly on the issue. National and regional publications such as MLK50 and the Associated Press also covered their work extensively.

“We are seeing the movement building in Memphis in ways no one really had anticipated,” Pearson said before the cancellation. “One of the main things [polluters] seek to do in a community is divide it…but the spirit in Memphis is stronger than this crude oil pipeline company.”

“We did not know how we were going to do it, we just knew we had to stop [the pipeline] for the community that made us who we are,” Jones adds. “I was always told to never forget where you come from and that’s why I [stood] against it.”

Now that the Byhalia project is cancelled, Memphis-area citizens are calling for more permanent safeguards to protect their clean water and the Memphis Sand Aquifer from similar threats in the future.

And the worldwide impact of their struggle isn’t lost on them. Concludes Pearson, “What’s happening here is having ripple effects in how we view justice across the country.”