The results are finally in: 2020 was one of the hottest years in recorded history, according to data released today by NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. By NASA’s reckoning, it tied with 2016 for the hottest year in the books, while NOAA placed it in the number-two spot.

Regardless of its final placement, 2020’s feverish heat came without the major El Niño event that boosted global temperatures to a new high four years ago—and thus the year provides an important marker of the power of the long-term warming trend driven by human activities that emit greenhouse gases. “Until we stop doing that, we’re going to see this over and over again,” says Gavin Schmidt, director of NASA’s Goddard Institute for Space Studies, which keeps the agency’s temperature records.

In the final reckoning, 2020 was just 0.04 degree Fahrenheit behind 2016, according to NOAA (whose records go back 141 years). NASA found that 2020 was in a statistical tie with 2016. The variation between NASA and NOAA is partly because of the different ways each processes temperature data: NOAA does not extrapolate temperatures over the Arctic to make up for missing data there, and Schmidt says leaving that information out misses one of the fastest-warming spots on the globe.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

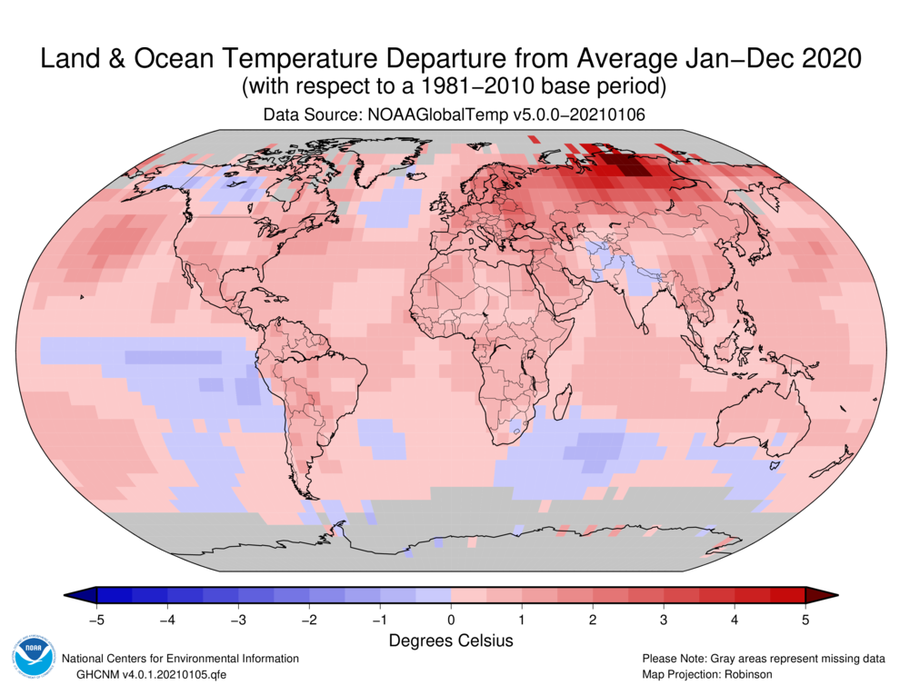

One of 2020’s notable hotspots was Siberia, which was covered by an angry, deep-red blotch on global temperature maps. The region has been exceptionally hot since the beginning of that year, contributing to last January being the planet’s warmest on record. At one point the Siberian town of Verkhoyansk reported 100.4 degrees F. If this figure is verified by the World Meteorological Organization, it would be the first time recorded temperatures above the Arctic Circle have surpassed 100 degrees F.

Where temperatures have been warmer or cooler than average across the globe in 2020. Credit: NOAA

But this hotspot is not the sole reason that 2020 is at the top of the charts. Above-average temperatures were prevalent over large swaths of the globe. Europe and Asia had their hottest years on record, while South America and the Caribbean had their second-hottest, according to NOAA. The world’s oceans had their third warmest year. And there are always hotspots somewhere on the globe in a given year—so the one in Siberia is not all that unusual, Schmidt says. In 2019, for example, the main hotspot was elsewhere in the Arctic, in an area encompassing parts of Alaska, Canada and Greenland.

But broad areas of warmth and more localized hotspots are both linked to the long-term warming trend. “It’s gotten to the point where these intense heat waves would not be possible in any reasonable amount of time in a non-human-perturbed climate,” Schmidt says. A recent analysis of the role of global warming in Siberia’s prolonged heat found that such extremes would happen around once every 80,000 years in the absence of anthropogenic warming. These extremes are also happening over larger areas than they would in the absence of climate change, Schmidt says.

Importantly, 2020’s ranking at or near the top of the charts happened without the major El Niño event that helped propel 2016 to the top of the rankings. During an El Niño a band of warm ocean water covers the tropical Pacific Ocean, which can raise global temperatures. “When we have a big El Niño event, we do tend to have a record being broken,” Schmidt says, adding that this factor is often what causes the record to be broken by a large amount. But an El Niño is not necessary to take the lead: both 2014 and 2015 became the then-hottest year without one. “We’ve broken the records pretty consistently, even in years where we didn’t have an El Niño,” Schmidt says. This fact also speaks to the way the inexorable rise in warming has been steadily elevating the baseline temperatures that events such as El Niño or heat waves add to. Recently, even years with a La Niña event (which tend to be cooler, because colder ocean waters spread across the tropical Pacific) are warmer than El Niño years of decades past.

To that point, 1998—the one 20th-century year that had until recently remained in NOAA’s top 10 warmest—did have a major El Niño. It was a record-setting outlier at the time. But because of global warming, the earth’s baseline temperature has shifted so much higher that 1998 is now being left in the dust (2016, which had a similarly strong El Niño, was 0.63 degree F hotter). It has now officially been knocked out of NOAA’s top 10. All of the 10 warmest years in its records have occurred since 2005—and the top seven have occurred since 2014—says Ahira Sánchez-Lugo, a climatologist at NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information.

That bunching of heat records in more recent years is, again, because of long-term warming, which is stacking the deck for ever more frequent records. A 2017 analysis in Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society noted that between the late 19th century and 1980, new records for the hottest year would happen about every eight to 11 years. Since 1981, they have been occurring about every three to four years.

So 2020’s high ranking was not entirely unexpected—and is yet another stark example of how far the earth’s climate has deviated from its natural course. “Everything that you see is conditioned on this long-term trend,” Schmidt says. “I work for NASA, but it’s not rocket science.”