A hundred years ago, in the Texas counties along the U.S.–Mexico border, a decade-long flurry of extralegal killings perpetrated by Texas Rangers, local law enforcement, and civilian vigilantes took the lives of thousands of residents of the United States who were of Mexican descent, and pushed many more across the border into Mexico. This record of death and intimidation, which irrevocably shaped life in those border counties, has not been commonly taught in the state’s mainstream school curricula or otherwise recognized in official state histories. Mexican-American communities, however, have preserved the memory of the violence in family archives, songs, and stories. “To many Mexicans, contemporary violence between Anglos and Mexicans can never be divorced from the bloody history of the Borderlands,” write William D. Carrigan and Clive Webb in their history of lynchings of Mexican-Americans. “They remember, even if the rest of the country does not.”

Belatedly, tentatively, Texas has begun to reckon with this bloody history. As election-year rhetoric around the border and Mexican immigration has reached new levels of xenophobia and racism, the state—goaded by a group of historians calling themselves Refusing to Forget—has taken steps toward commemoration of the period called “La Matanza” (“The Killing”), with an exhibit at the Bob Bullock Texas State History Museum and three historical markers soon to be unveiled. For a state that has long refused to come to terms with those years—sealing transcripts of a Congressional investigation into the killings and waxing nostalgic about the Texas Rangers despite their involvement—it’s something like progress, even if the legacy of this violence will require far more than exhibits to expiate.

The deaths that occurred between 1910 and 1920 are part of a longer history of lynching of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in the United States—itself little-discussed in comparison with the parallel history of violence against black Americans. Carrigan and Webb identify waves of violence against Americans of Mexican descent in the 1850s (when Mexicans were forcibly expelled from many mining camps in California), the 1870s (when Mexicans and Americans both took to raiding farms and ranches across their respective borders), and the 1910s. While a mob’s stated reason for lynching black victims tended to be an accusation of sexual violence, for Mexicans in the United States, the reason given was often retaliation for murder or a crime against property: robbery, or what was sometimes called “banditry.”

Property—in the form of land—was the underlying cause of the Texas border violence that took place in the second decade of the 20th century. At the turn of the 20th century, an epic, often illegal, transfer of land began, moving ownership from Tejanos living in the border counties of Texas to newly arrived Anglo farmers and ranchers. (Because the people living through this history did not use the term “Mexican-American” to describe themselves, I’m following the lead of the Refusing to Forget historians, and using the terms “Texas-Mexicans” or “Tejanos” to describe Texas residents of Mexican descent.) The advent of the railroad, which reached the border city of Brownsville in 1904, made Anglo expansion onto historically Mexican land possible, seriously shifting the balance of power in the land along the Rio Grande.

This area had fallen within the borders of the United States since the middle of the 19th century, when the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the Mexican-American War and made the river the new boundary between the two countries. But it had remained culturally Mexican, with many Mexican residents staying on the ranches where they had been living—which were now, legally, located in Texas. Between the signing of the treaty and the advent of the railroad, the area was predominately Mexican, with a small number of Anglo settlers mixing into the culture, intermarrying with Tejano neighbors and learning to speak Spanish. As historian John Moran Gonzalez put it to me: “You paid your taxes in dollars, but you paid for your groceries in pesos. English was the language of government but everybody spoke Spanish.” The Border Patrol wasn’t founded until 1924; in the meantime, people went back and forth across the river easily.

After the railroad arrived, irrigation companies soon followed suit, and the Rio Grande Valley’s naturally fertile lands began to look more and more appealing to Anglo immigrants. The price of land went up, and so did taxes; Mexican ranchers found it hard to pay. “Sheriffs sold three times as many parcels for tax delinquency in the decade from 1904 to 1914 as they had from 1893 to 1903,” writes Benjamin Heber Johnson in his book Revolution in Texas: How a Forgotten Rebellion And Its Bloody Suppression Turned Mexicans Into Americans. “These sales almost always transferred land from Tejanos to Anglos.” Because records of land ownership in the region had been poorly maintained when the land was less desirable, Anglo settlers could often challenge ownership in court. If the Tejano living on the land didn’t have the funds to fight such a challenge, they ended up selling parcels in order to pay legal fees. Sometimes, Johnson writes, white ranchers “resorted to the simple expedient of occupying a desired tract and violently expelling previous occupants.” The end result was catastrophic for the Tejano community: Between 1900 and 1910, more than 187,000 acres of land transferred from Tejano to Anglo hands, in just two Texas counties (Cameron and Hidalgo). Many who lost their land ended up working on it, paid, not well, by its new owners.

***

Just as these white settlers began moving into the region, a series of events in Mexico (a recession in 1906; the Mexican Revolution in 1910) caused an increase in Mexican immigration, as people fled instability in their home country. The decadelong revolution in Mexico ended the reign of Porfirio Diaz, a dictator who had supported wealthy landowners and industrialists. The reforms called for by Mexicans who challenged Diaz’s rule included land redistribution. This scared Anglo Texans, who worried that revolutionaries might look at Texas—where some Anglos had begun to accumulate huge tracts of land that once belonged to Tejano smallholders—and see fertile ground for protest and action.

Bullock Texas State History Museum

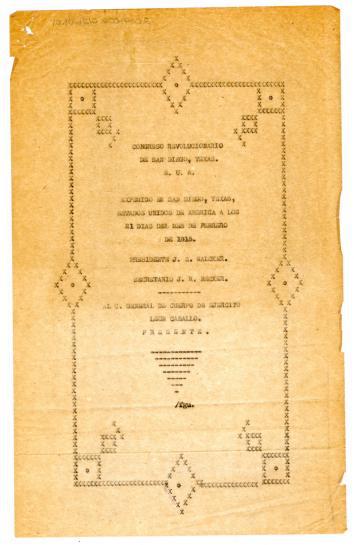

Groups like the revolutionary Junta Organizadora del Partido Liberal Mexicano (PLM), which had opposed the U.S.–backed Diaz regime, did in fact influence some Mexicans living in the United States. When a copy of the Plan de San Diego, a fiery document calling on Mexicans (and a list of other minority ethnic groups) to rise up against Anglo rule and establish their own government in the Southern United States via armed struggle, surfaced in Duval County, Texas, in 1915, the climate turned toxic. Anglo ranchers, reading news of the Plan de San Diego in their newspapers, felt increasingly threatened. Throughout that year, groups of Mexicans and Mexican Texans, some operating with the political and material support of revolutionaries in Mexico, raided railroad lines and communication infrastructure in South Texas.

A number of raids on Anglo ranches did occur. Occasionally, the raiders even killed ranchers outright. Johnson starts his book with the story of Nellie Austin, an Anglo woman who watched her husband and son killed by armed Sediciosos, as the rebels came to be called. “I went first to my husband and found two bullet holes in his back one on each side near his spinal column,” Austin later said of the day the men came to her farm. “My husband was not quite dead but died a few minutes thereafter. I then proceeded to my son Charles who was lying a few feet from his father; I found his face in a large pool of blood and saw that he was shot in the mouth, neck and in the back of the head and was dead when I reached him.”

The Austins, Johnson points out, were “important local segregationists whose personal behavior had angered many Tejanos”; it seems likely that they were targeted because their attitude toward Mexicans was so brutal. The elder Austin was known to kick field workers he considered to be working too slowly. According to a local law enforcement officer, six men in the party that killed him had worked for him, and had felt “the toe of his boot.”

The actions of the Sediciosos who attacked Anglo property during the first half of the decade pose an interesting problem for historians telling the story of the deaths of Tejanos during the same period. How to account for the fact that those many extralegal killings that took place between 1915 and 1920 were inspired not only by phantoms living in the minds of people who had so recently moved into the region and dispossessed its residents, but also by actual acts of resistance?

After visiting the Refusing to Forget group’s exhibit at the Texas State History Museum, journalist Aaron Miguel Cantú wrote a critical review of it for the New Inquiry, decrying the relative absence of the Sediciosos in the exhibit’s story of the unfolding violence in South Texas. A true representation of the history, Cantú wrote, would show that “the Rio Grande Valley was the last place where a gunslinging anti-government insurgency seriously threatened US borders.” To Cantú, the diminished presence of this resistance in the exhibit’s storyline heightens the sense that the Texas Mexicans who died in the ensuing violence were innocent victims, and unfairly sidelines the Tejanos and Mexicans who did fight back against the huge social and economic changes occurring in the border counties.

***

Even when you fully account for the actions of the Sediciosos, the Anglo response to these raids was a brutal overreaction, killing (and driving back across the border) a lopsided number of Tejanos and Mexicans.

The Texas Rangers were founded in 1836. As historian Kelly Lytle Hernandez writes in her history of the Border Patrol, Rangers—roaming law enforcement officers who became legendary for their frontier toughness—were key to the Anglo settlement of Texas. Their heroic image among white settlers in the 19th century was earned at a price paid by everyone else, as the Rangers “battled indigenous groups for dominance in the region, chased down runaway slaves who struck for freedom deep within Mexico, and settled scores with anyone who challenged the Anglo-American project in Texas,” Hernandez writes.

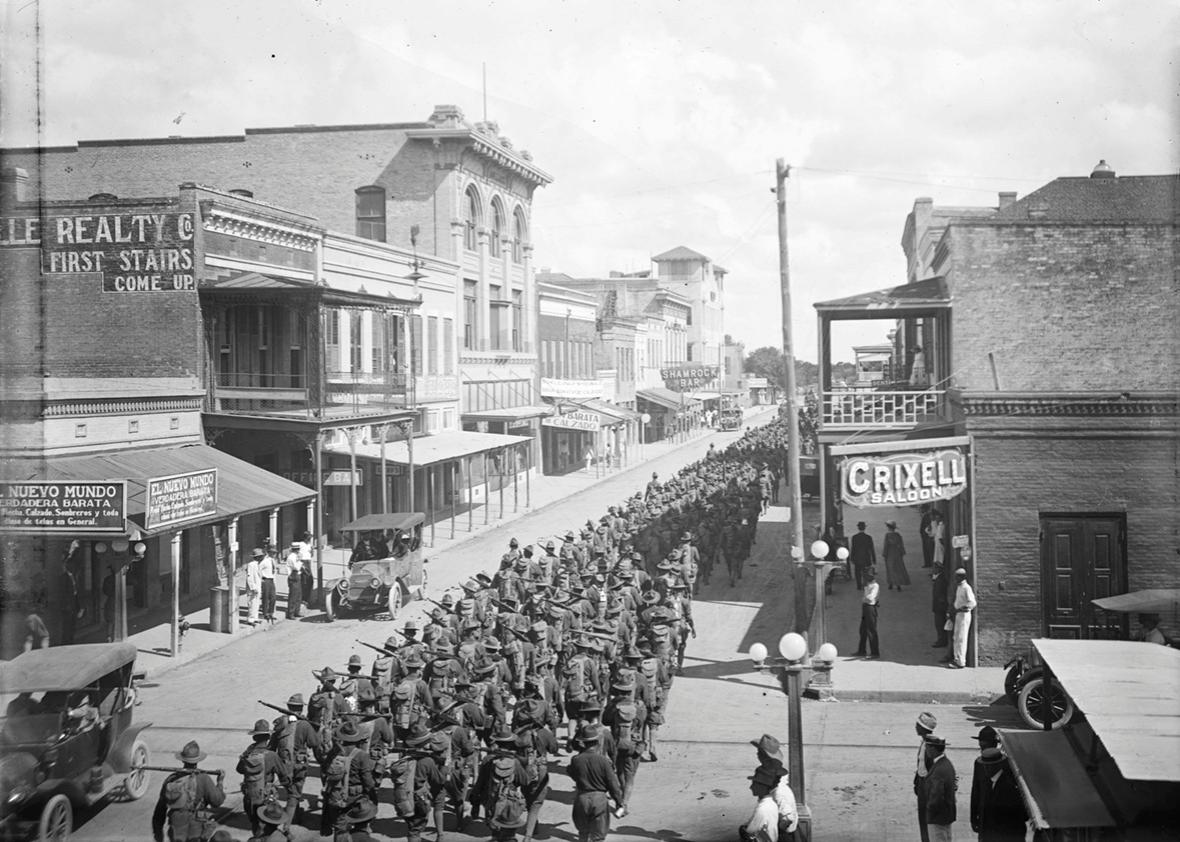

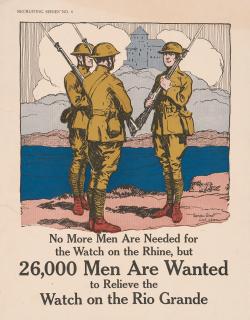

Gordon Grant/Library of Congress

Between 1910 and 1920, the state drastically upped the number of Texas Rangers who patrolled the area. The Mexican Revolution and the raids by the Sediciosos were one trigger for the increase in law enforcement; World War I was another. When the war began, some Americans feared that Mexico might side with Germany. The fears made things worse for Texas Mexicans in the border region, as Rangers and local law enforcement were charged with determining the loyalties of the local population, and delivering “slackers” to draft boards. In an article in the journal American Quarterly, historian Monica Muñoz Martinez writes that the force went from 13 Rangers in September 1913 to around 1,350—paid and unpaid—by the end of the war. “The dramatic increase in the force led to rampant hiring with little administrative oversight,” Martinez notes. The creation of a new category of Ranger, called the “Loyalty Ranger,” allowed for quick induction of less-qualified personnel. The Rangers assisted local sheriffs and landowners, acting as enforcers for Anglo ranchers. During this time, the Rangers, little supervised and much valued by scared Anglo citizens of the region, cemented their place as the agents of white rule in the borderlands.

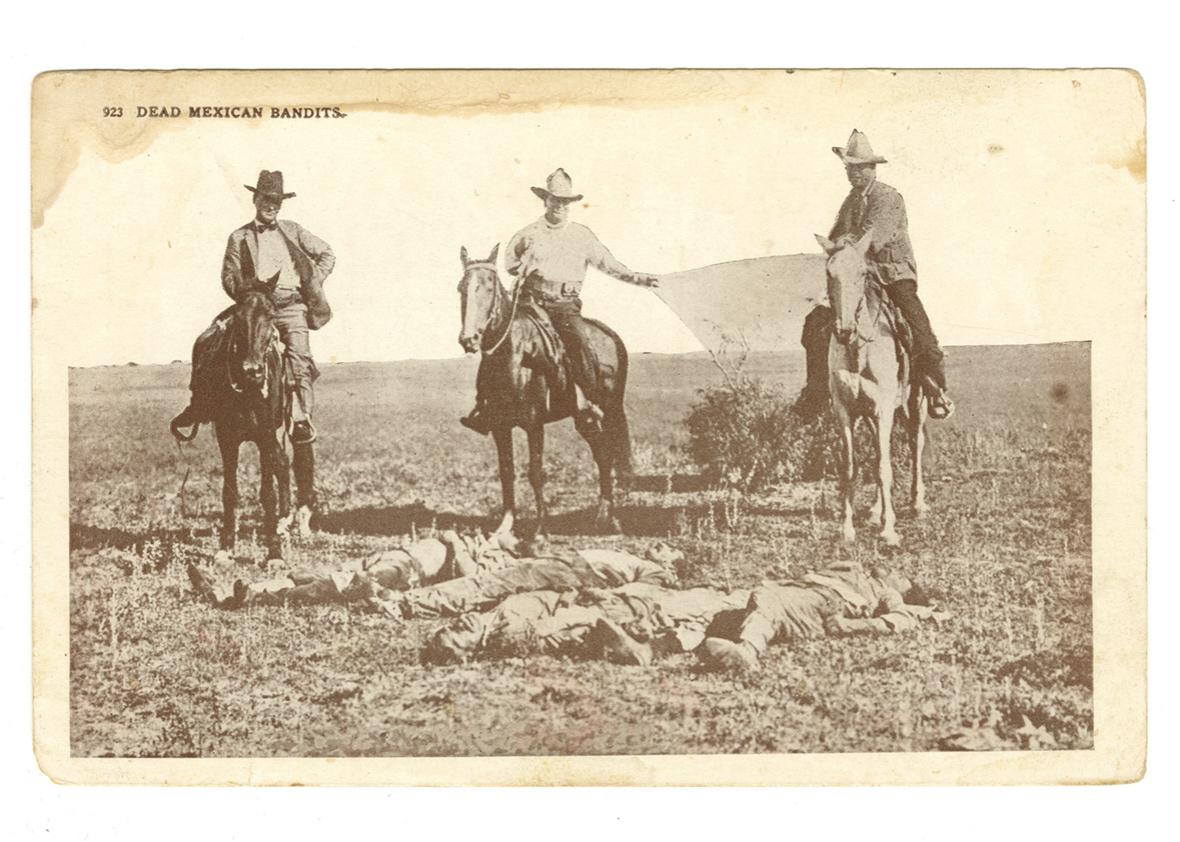

Later testimony recorded the way the Rangers took advantage of their power to carry out extralegal killings in the far distant reaches of the rural border counties in the wake of the discovery of the Plan de San Diego. In October 1915, after raiders derailed a train in Olmito, Texas, near Brownsville (the railroad, as a primary agent of Tejano dispossession, was a frequent target), Rangers and civilian helpers captured 10 ethnic Mexicans, hanging and shooting them on the spot.* The local sheriff, W.T. Vann, later said that Ranger Captain W.T. Ransom was responsible:

Captain Ransom had [four of the suspects] and walked over to me and says, I am going out to kill these fellows, are you going with me? I says no, and I don’t believe you are going. He says, if you haven’t got guts enough to do it, I will go myself. I says, that takes a whole lot of guts, four fellows with their hands tied behind their backs, it takes a whole lot of guts to do that.

Many killings in the initial period of violence in 1915 resolved old conflicts between Anglo and Tejano neighbors, in the favor of the Anglo. Some Anglo landowners who had long desired land owned by Tejano neighbors found ways to accuse them of raiding and scare them across the river, then offered them bottom dollar for their abandoned ranches, securing legal title through intimidation.

One killing in particular highlights how little the social power that Tejano elites had accumulated during their decades in the region could accomplish, when up against the impunity the Rangers felt in the months after the discovery of the Plan de San Diego. On Sept. 27, 1915, W.T. Ransom and two civilians killed Jesus Bazán and Antonio Longoria, Tejano ranchers in Hidalgo County and members of the local elite (Longoria was a county commissioner). The two—Bazán, the father-in-law, and Longoria, his son-in-law—had lost horses to raiders and decided to report it to the Rangers who were camping nearby. Monica Martinez writes that the prevailing climate made the choice to report this crime difficult. “On the one hand, [Longoria and Bazán] knew that if they reported the robbery to local or state police, their kin could face the raiders’ wrath for aiding local authorities,” she writes. “On the other hand,” if they kept quiet and the horse thieves were arrested, “the families could be accused of supporting bandit activities and risk brutal reprisals.”

They decided to report the theft. After the pair rode away from the Ranger camp on horseback, Ransom, accompanied by two Anglos, got in a Model T and drove behind them. He eventually caught up, and the three men shot the Tejano riders in the back. Workers on the ranch witnessed this event, and Ransom warned them, Martinez writes, “not to bury or move the bodies. Taking this additional step of intimidation denied the bodies a proper burial and forced neighbors and friends of the dead to endure an extreme act of disrespect.” In killing such high-status members of the Tejano community and refusing them burial, Ransom demonstrated the absolute nature of Ranger power over the borderlands, making a vivid argument for Ranger invincibility.

Bullock Texas State History Museum

Such disrespect of the testimony, property, and lives of Tejanos, even the most elite, was endemic during 1915. The way local newspapers wrote about the violence shows how the killings drew from, and hardened, burgeoning racism, in a region where the Anglo minority had once lived in relative peace with their Tejano neighbors. As was often the case with lynchings of African-Americans, Anglo papers reported on the deaths of 1915 with a boosterish attitude that seems macabre to a modern reader. Johnson quotes a few: “The known bandits and outlaws are being hunted like coyotes and one by one are being killed … The war of extermination will be carried on until every man known to have been involved with the uprising will have been wiped out,” wrote the Lyford Courant. The editor of the Laredo Times argued: “The recent happenings in Brownsville country indicate that there is a serious surplus population there that needs eliminating.” A newspaper in San Antonio reported: “The finding of dead bodies of Mexicans, suspected for various reasons of being connected with the troubles, has reached a point where it creates little or no interest … It is only when a raid is reported or a [white] American is killed that the ire of the people is aroused.”

***

Raids by Tejanos and Mexicans associated with the Revolution died down in 1916, but the tension between Tejanos and Anglos remained. Tejano residents of South Texas felt completely unprotected by the law. In a 1916 petition to President Woodrow Wilson and the governor of Texas, the Tejano residents of Kingsville described the conditions that prevailed during that time:

One or more of us may have incurred the displeasure of some one, and it seems only necessary for that some one to whisper our names to an officer, to have us imprisoned and killed without an opportunity to prove in a fair trial the falsity of the charges against us…Some of us who sign this petition may be killed without even knowing the name of him who accuses. Our privileged denunciators may continue their infamous proceedings—answerable to no one.

The Kingsville residents reported an incident in which two community members were arrested and taken by an officer to Brownsville; they were killed en route. “The place where and by whom killed, is not learned,” the petition states in formal passive voice. “Before being tried, and while they were still presumed innocent under our law, they were killed. And their widows, after making diligent inquiry, are given no information as to where the bodies may be found.” Confirming the petitioners’ fears that they might be retaliated against for preparing the complaint, the Anglo attorney who helped the group prepare this petition reported that a Ranger later came to a courthouse where he was working, asked him, “Are you the son of a bitch that wrote that petition at Kingsville?” and pistol-whipped him.

In 1918, State Rep. José T. Canales called for hearings to investigate the recent conduct of the Texas Rangers in 19 cases of wrongful dispossession, assault, and murder. Canales wrote a bill that would require Rangers to post bond before serving (to guarantee their good conduct) and to be otherwise more tightly regulated by the state. That Canales, the only state legislator of Mexican descent, managed to raise these questions in an official forum is remarkable. But reading the transcripts of the 1919 hearings (which were kept sealed until the 1970s and are now available in PDF form) is an exercise in frustration. Witness after witness stonewalls the legislator, evincing respect for the Rangers, defense of their conduct, and disbelief at any allegations Canales advances.

A few Anglo witnesses did speak on behalf of Tejano citizens. Playing to his Prohibitionist Progressive allies in the legislature, Canales emphasized the drunkenness and dissipation of the Rangers; he called Virginia Yeager, an Anglo witness who was a suffrage activist, to speak about her own encounters with the Rangers. “They have no regard for either the civil or military laws,” Yeager wrote in her letter to the legislature, included in the transcripts. “They make their own out of a bottle.” Witnesses both Anglo and Tejano spoke about “rough treatment,” drunkenness, and the “evaporation,” or disappearing, of citizens of Mexican descent. The massacre at Porvenir was perhaps the most serious incident addressed in the 1919 hearings. Rosenda Mega, “47 years old, American citizen, born at Fort Davis, Texas, but residing at Van Horn, Texas,” told the commission that he had special knowledge of this event. Mega had spoken with people who lived in the West Texas town of Porvenir, and heard them recount the story of the murder of 15 residents of the small village, which took place on Jan. 28, 1918. (Most of the remaining residents of Porvenir—around 140 of them—had fled to Mexico, and so were unavailable for comment.)

Soldiers and law enforcement mounted the assault on Porvenir in apparent retaliation for a raid on a nearby ranch. The residents told Mega that about 40 “American soldiers, Rangers, and Texas Ranchmen” searched the town, found no evidence of involvement, but selected a group of men to be killed anyway—perhaps as a warning. Mega’s testimony, filtered through the typewriter of the legislature’s stenographer, is brutal: “They took them about one-quarter of a mile from said ranch, and then in a very cowardly manner, and without examining any of them, shot them.” Listing the names of the dead, Mega added: “One of those killed was my father-in-law, in whom I had great faith, and with whom I have traded for many years.”

***

Canales’ bill, as he wrote it, didn’t pass. The bill the committee approved removed the requirements that Rangers be bonded, and while it called for the end of the Special Rangers, it allowed the governor to retain the power to expand the Ranger force at will. The legislature found evidence that the Texas Rangers were “guilty of, and responsible for, the gross violation of both civil and criminal laws of the state,” but failed to punish the force’s current leaders. Monica Martinez told me that although the official state narrative about the 1919 hearings was a story of redemption—as she summarized it, “the Texas Rangers were reformed, the numbers of the Rangers were reduced, and the bad apples were kicked out”—in actuality, many of the men who were named during the hearings went on to other jobs in Texas law enforcement.

“Those bad apples went on to be sheriffs in Austin, or they went on to help shape the Border Patrol, or they were prison guards in Houston,” says Martinez, pointing to the example of James Monroe Fox, a Ranger who resigned after being named as a participant in the Porvenir massacre. Fox spent some time working as a sheriff before returning to the Rangers. “The culture of policing didn’t change. There was a moment in 1919 where the state could take a stand against racial violence as a state policing regime, and it didn’t.”

Russell Lee Photography Collection/The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History/University of Texas at Austin

For Texas Mexicans, the welcome end of a decade of lynchings and executions ushered in a new era of racial discrimination known as “Juan Crow,” during which Mexican-Americans in Texas faced segregation in schools and public facilities and a further hardening of racial boundaries. Johnson points out that Canales’ treatment during the hearings, when he faced a hostile environment among his fellow legislators, was a sign of the times: “If a prominent, wealthy, powerful sitting member of the Texas House of Representatives was nothing more than ‘the greaser from Brownsville’ to a legislative colleague, and could be stalked and threatened by employees of his own government, then what hope for decent treatment from the state could ordinary citizens of Mexican descent expect?” Canales left the legislature soon after. It wasn’t until 1956 that another Mexican-American served.

In the years between the killings of the early 20th century and the 2000s, when a new series of scholarly books returned to the history of this period, the stories lived on in the minds of Mexican-Americans living in Texas, who transmitted memories of the violence through song, oral tradition, and literature. Martinez told me about one remarkable example of the way the history has been kept alive in the community, even as it went officially unrecognized. The family of Antonio Longoria and Jesus Bazan has been collecting information on the event for decades. Descendant Norma Longoria Rodriguez, Martinez told me, “conducted oral histories with the family, and created her own private archive of the lives of the men.” The Longorias “dedicated decades and spent thousands of dollars traveling to rural archives across the state. They’ve been trying to tell this history, really, for generations.”

Martinez told me that to the descendants of the victims of this period of violence, the exhibit’s placement in the Bullock, the official state history museum, was important. “When we got together as a group for the first time in 2013, we imagined a museum exhibit, and maybe having some kind of commemorative sculpture,” Martinez said. “It was really when we invited the families to join the conversation we found out that they wanted Texas state historical markers; they wanted state cultural institutions to host the exhibits. For them, it would have been a good gesture to have a commemoration and memorialization of the history of violence, but without the state involvement, they wouldn’t have felt like they had made much progress.”

For Martinez, the Bullock’s involvement should be just the beginning. “Collaborations with the Bullock and the Texas State Historical Commission are tremendous and are a great step forward,” she writes in a post on Process, the Organization of American Historians’ blog. “A state apology would go far in helping the public reckon with this period of violence. However, for me, until the state actually reforms ongoing policing practices in the state and on the border, an apology would be disingenuous.”

The damage done during this period has been lasting. Writing about this history in Latina magazine, journalist Cindy Casares points out that the Texas counties where the violence occurred are now the poorest in the state. Perhaps the state’s willingness to commemorate La Matanza in official venues will help visitors connect this poverty with history. And to ask themselves whether commemoration is enough.

*Correction, May 5, 2016: An earlier version of this article misstated that the October 1915 train derailment occurred near Lyford, Texas. It occurred near Brownsville, Texas, in Olmito. (Return.)