For Immediate Release, December 13, 2021

|

Contact: |

Michael Robinson, (575) 313-7017, michaelr@biologicaldiversity.org |

Wandering Mexican Gray Wolf in New Mexico Blocked by Border Wall

Endangered Wolf Populations Face Obstacles in Crossing, Finding Mates

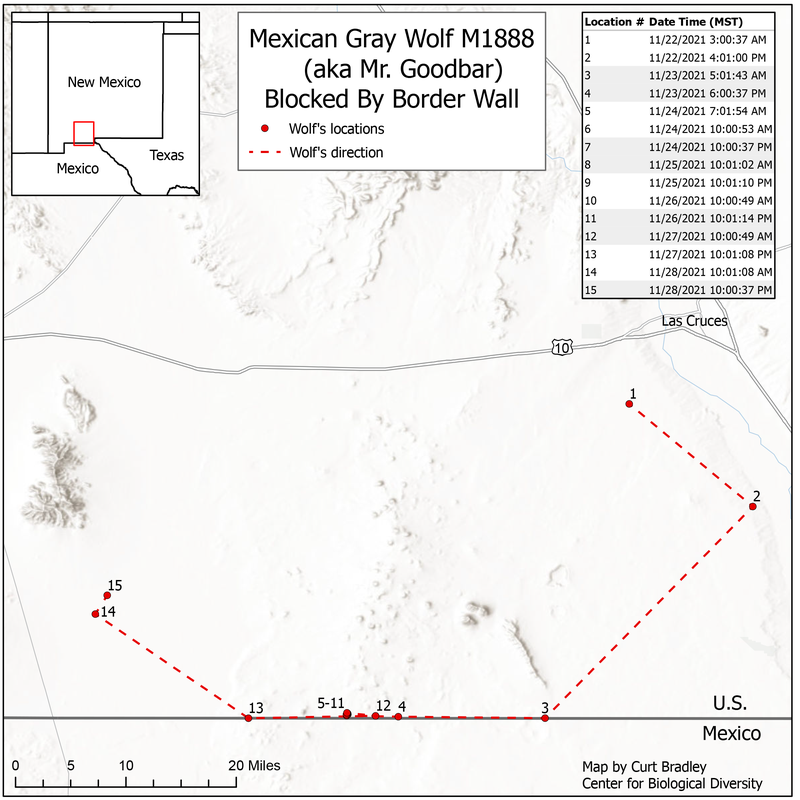

SILVER CITY, N.M.— In the first documented instance of the U.S.-Mexico border wall separating two endangered wolf populations, a Mexican gray wolf — likely in search of a new home and mate — was blocked at the border in New Mexico last month. The wolf’s GPS collar periodically beamed his locations to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which last week released them to the Center for Biological Diversity.

The wolf was born in the Sedgwick County Zoo in Kansas and named Mr. Goodbar before his 2020 release into the wild in Arizona. He spent Nov. 23 to Nov. 27 pacing along 23 miles of the border where the wall prevents wildlife from crossing.

“Mr. Goodbar’s Thanksgiving was forlorn, since he was thwarted in romancing a female and hunting together for deer and jackrabbits,” said Michael Robinson, a senior conservation advocate at the Center. “But beyond one animal’s frustrations, the wall separates wolves in the Southwest from those in Mexico and exacerbates inbreeding in both populations.”

On Nov. 28 Mr. Goodbar headed northwest, away from the border. He was recently located farther north, in the Gila National Forest where most Mexican wolves live.

The Trump administration built walls even in remote New Mexico where few people cross. Conservationists have called for these walls to be removed and have identified priority stretches of the borderlands to restore, including where Mr. Goodbar was impeded.

Bollard-style walls obstruct the natural movements of wildlife. In addition to Mexican wolves, dozens of rare wildlife species that also need to roam live in this region of the borderlands, including kit foxes and ringtails.

In early 2017, in separate events, two wolves from Mexico entered the United States. One crossed where Mr. Goodbar later could not, then returned to Mexico. Two months later, another wolf crossed into Arizona, and the Service captured her to placate the livestock industry. She is still in captivity and is Mr. Goodbar’s mother.

“President Biden should knock down the wall,” said Robinson. “Allowing Mexican gray wolves to roam freely would do right by the sublime Chihuahuan Desert and its lush sky-island mountains. We can’t allow this stark monument to stupidity to slowly strangle a vast ecosystem.”

Background

In the early- to mid-20th century, the U.S. government exterminated wolves in the western United States on behalf of the livestock industry and began poisoning wolves in Mexico too. Saved by the 1973 passage of the Endangered Species Act, a total of seven wild-caught Mexican gray wolves were successfully bred in captivity and their descendants reintroduced to the United States in 1998 and to Mexico in 2011.

More than 200 Mexican wolves live in the United States today and around 40 in Mexico. But genetic diversity in the U.S. population has declined. Both populations require genetic connectivity for long-term survival.

The Center for Biological Diversity is a national, nonprofit conservation organization with more than 1.7 million members and online activists dedicated to the protection of endangered species and wild places.