DMV Color features an eclectic assortment of contemporary works by 20 women of African American, Asian American, and Latina heritage. The artists’ books, graphic novels, photobooks, and zines depict intimacies of family life, legacies of enslavement, effects of rampant development, dislocation and newfound freedoms tied to immigration, and other topics.

This virtual exhibition includes new audio clips of seven artists describing their featured books, inspirations, and overall artistic practice.

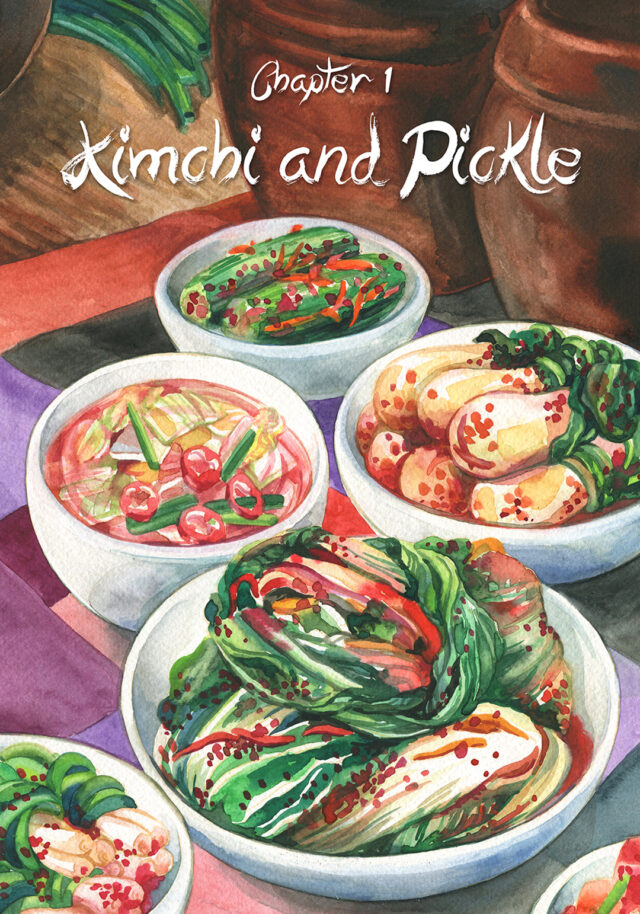

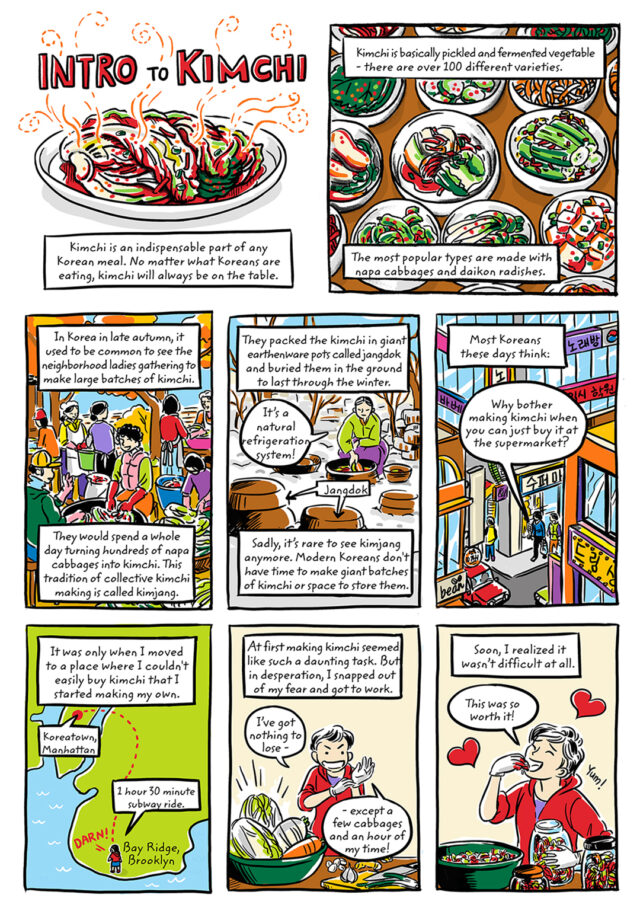

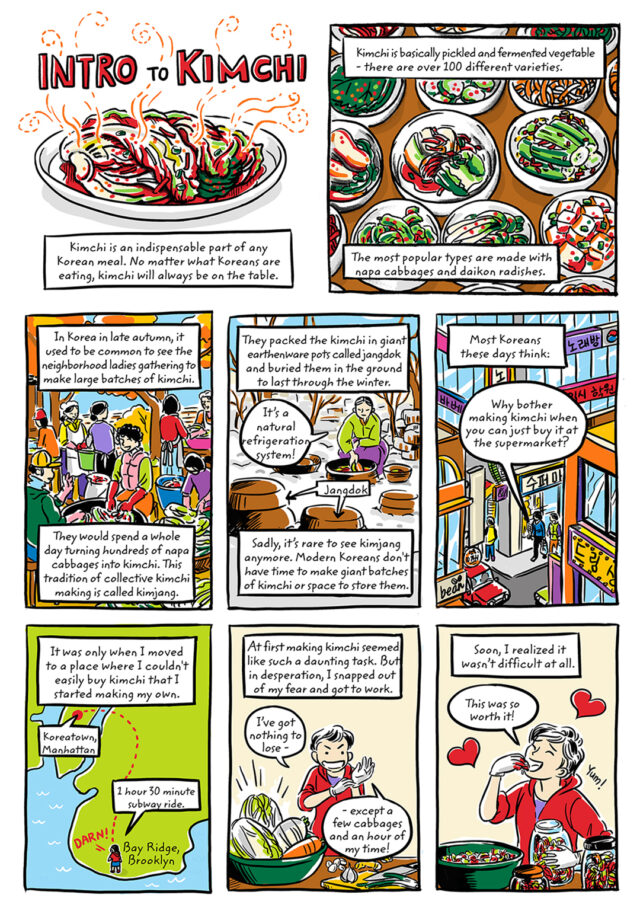

Robin Ha, Cook Korean!, 2016; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

The District of Columbia and its extended surroundings—from Baltimore, Maryland, to Richmond, Virginia—have welcomed artists of African, Asian, Native, and Latinx heritage. This history stretches from the 1700s and earlier, boosted by the influx of formerly enslaved African Americans who flocked here during the Civil War and Reconstruction. More recently, immigrants from East, West, Central, and Southern Africa; Central and South America; Central Asia; the Middle East; Southeast Asia; and other regions have settled in the DMV as they flee armed conflicts, repressive governments, and economic crises. Some featured artists lived in the region for only a short time, but experienced a lasting impact on their creative endeavors. Women of these diverse heritages and DMV experiences, often united by a desire to be freed of restrictive social norms, have learned from and inspired one other in their creative endeavors.

Magdalena Cordero, Poems by Gabriela Mistral, Translations by Ursula K. Le Guin, Long Chilean Gaia, 2016; Artist’s book; Photo by Emily Shaw, Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Historically, the DMV has been home to some of the world’s most respected African American artists, many of them, such as Elizabeth Catlett, linked to Howard University. These artists especially began rising to prominence in the early and mid-twentieth century. Although no topic—from environmental crisis to romantic love—is out of bounds for the artists in DMV Color, many share a common theme in their work: the embrace of cultural identity. Here these identities are conveyed in varied mediums, but signifiers such as food, the admonitions of grandmothers, textiles, and childhood memories can be found across the boundaries of culture and form.

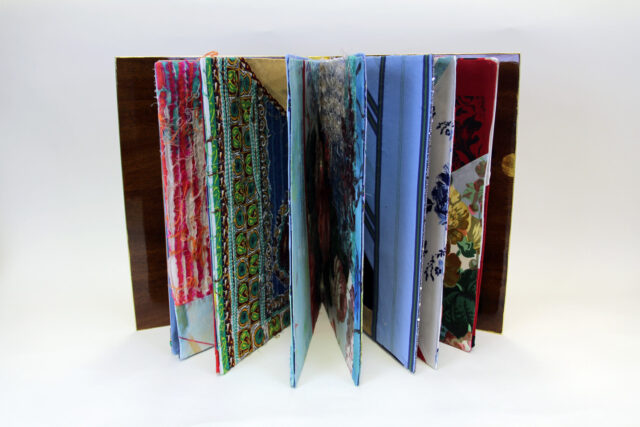

IBe’ Crawley, My Cotton Book, 2010; Artist’s book; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Emily Shaw, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

In this work, Suzanne Coley imagines and gives voice to a woman’s painful mourning of a son drowned while crossing the Mediterranean from North Africa in hopes of a better life in Europe. The artist responded to the loss of nearly 16,000 migrants’ lives in the Mediterranean in the last five years. All I Have is one of twelve books that Coley constructed from textiles given to her by the Warren M. Robbins Library, National Museum of African Art.

Suzanne Coley, All I Have, 2018; Artist’s book; Courtesy of the artist; On loan from Private collection; Photo by Emily Shaw, Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Hear Suzanne Coley talk about All I Have

“All I Have is part of a larger year-long project inspired by African textiles I received from the National Museum of African Art Library. While working on this project, there were many news reports about migrants traveling in unsafe overcrowded boats in the Mediterranean Sea from North Africa to Europe. Strong winds and bad weather conditions could easily capsize these boats, drowning everyone on board. In the last five years nearly 16,000 migrants have drowned while crossing the Mediterranean from North Africa in hopes of a better life in Europe. One survivor of these many death voyages described her ordeal as, ‘It was my only hope.’ In the artist book All I Have, I imagined her story and gave voice to a mother’s painful morning of the loss of her son while crossing the Mediterranean Sea.”

Suzanne Coley, All I Have, 2018; Artist’s book; Courtesy of the artist; On loan from Private collection; Photo by Emily Shaw, Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

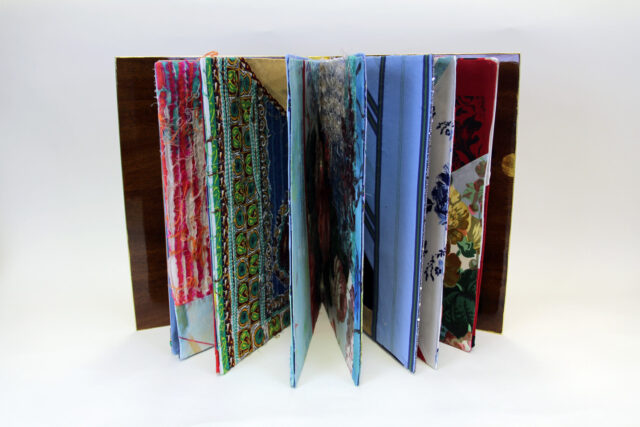

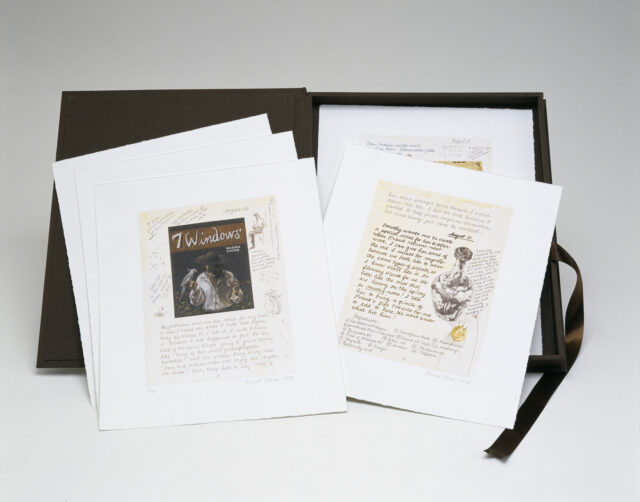

In Seven Windows, Renée Stout offers a glimpse into the world of her alter ego, Madam Ching, a mysterious fortune-teller and root worker, an herbalist associated with mysticism and folk magic. Arranged in the form of a journal, this artist’s book features individual pages with texts describing Madam Ching’s daily activities—brewing perfumes and love potions, buying and selling exotic herbs, and reading letters from friends and lovers.

Renée Stout, Seven Windows, 1996; Iris prints on paper, 10 x 12 in.; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Museum purchase: United States Department of Education Fund; © Renée Stout

Malaka Gharib’s graphic memoir is a joyous tribute to her immigrant family. The daughter of a Catholic Filipino mother and a Muslim Egyptian father, Gharib navigates her coming of age between her Filipino and Egyptian heritage while adapting to white American culture. Her childhood memories and adolescence are vividly expressed through her red, white, and blue color palette and playful drawing style.

Malaka Mercene Gharib, I Was Their American Dream, 2019; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Malaka Gharib describes her favorite page in I Was Their American Dream

“Hi, my name is Malaka Gharib, and I’m going to share with you a little bit about my favorite page in my book I Was Their American Dream. It’s a picture of me – a close up – awake at night reflecting on something that some people at school had told me the day before, that I was whitewashed, and sort of grappling with all the feelings of that. Feeling a little confused.”

Malaka Mercene Gharib, I Was Their American Dream, 2019; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Inspired by the cosmologies revealed by Mexico’s archaeological wonders, Jihae Kwon’s To the New Land depicts places of worship, movements of the sun and stars, and imagery of farming and animals to tell the story of a journey taken by indigenous people to the Americas.

Jihae Kwon, To the New Land, 2014; Artist’s book, Published by Corcoran College of Art + Design, Washington, DC; Photo by Jennifer Page, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

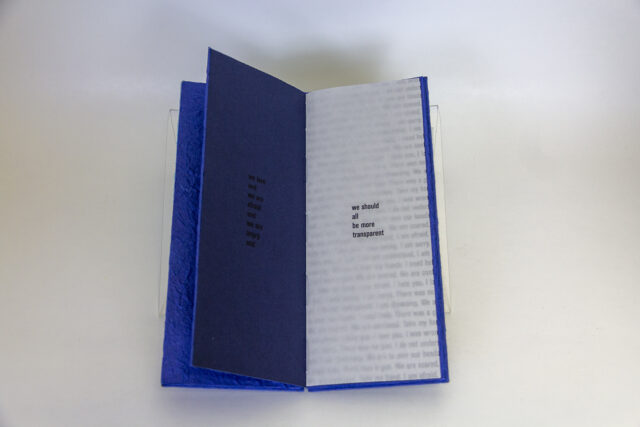

As a poet and librarian, Jamila Zahra Felton gravitated to the book arts as a form of creative expression that melds her various interests. Her works explore themes of memory, love, identity, and history.

we love

and

we are

afraid

and

we are

angry

and

we should

all

be more

transparent

Jamila Z. Felton, The Deep End: Or, Some of Us Learned How to Swim, 2016; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

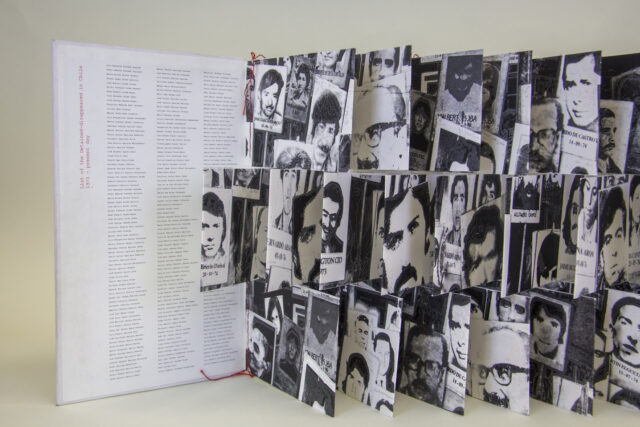

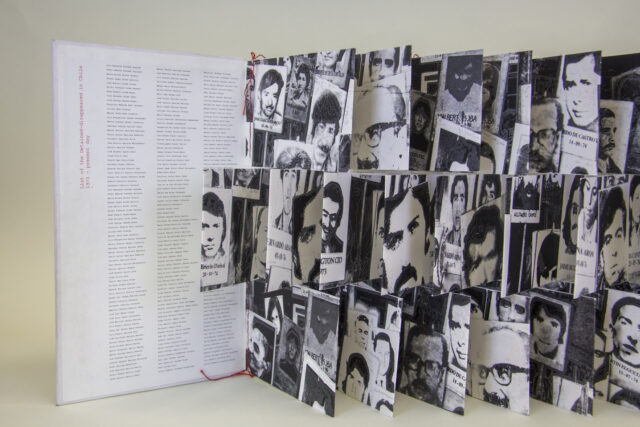

Thousands of Chileans flocked to the DMV to escape the 1973–90 military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet. In Their Memory, based on María Veroníca San Martín’s archival research, documents the disappearance and torture of Chilean citizens under Pinochet. The work invites viewers to grapple with the erasure of the tumultuous era’s human rights injustices and violent political history.

Maria Veronica San Martin, In Their Memory, 2012; Artist’s book; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Emily Shaw, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

María Veroníca San Martín on In Their Memory

“In Their Memory is an institutional critique I created in 2012. It’s a book of resistance. It carries forward the broadest we can by the family of the Disappeared in Chile during the military dictatorship. More than 40,000 political prisoners were victims of torture, executions, and exile; and more than 3,000 people were ‘disappeared’. It is in honor to the missing and their families that this book seeks to disseminate and communicate these human rights violations. By documenting the identities of the victims, the book also invites to reflect and put forward the message of hope founded in truth. Due to the current social-political situation, I decided to print a second edition, to not forget twice.”

Maria Veronica San Martin, In Their Memory, 2012; Artist’s book; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Emily Shaw, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

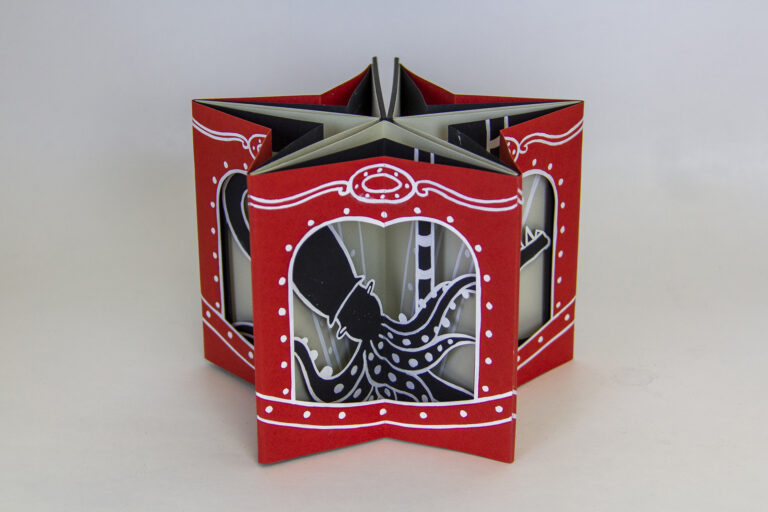

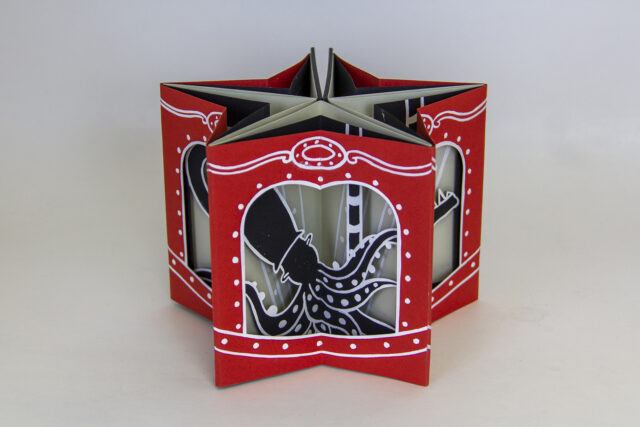

A twist on the idea of a carousel as a joyous and carefree space (and on the book arts term for this form), Jihae Kwon’s work depicts human-eating plants and animals, subverting expectations in hand-painted gouache.

Jihae Kwon, A Different Kind of Carousel, 2014; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

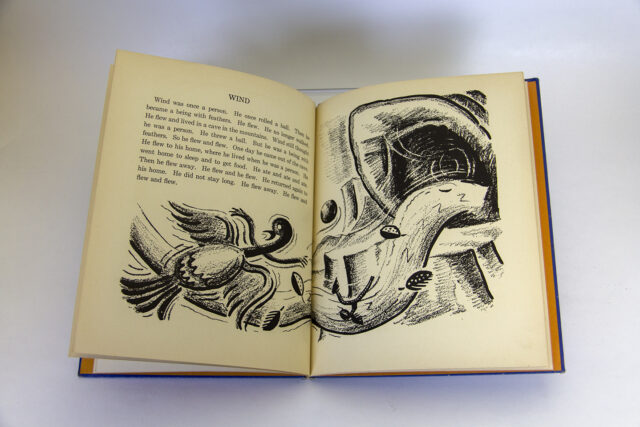

A member of the Howard University art department for forty-seven years, Loïs Mailou Jones created wide-ranging artwork that reflects influences from her extensive international travel. This 1938 children’s reader combines illustrations by Jones with text by Helen Adele Johnson, a prominent African American educator who worked in the South during the first part of the twentieth century.

Negro Folk Tales for Pupils in the Primary Grade (Book 1), text by Helen Adele Whiting, illustrated by Loïs Mailou Jones; Washington, D.C.: The Associated Publishers, Inc., 1938

In this meditation on man-made environmental degradation, Julie Sheah visualizes trees taking their revenge on humans.

Julie Sheah, Dream Book I, 2014; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

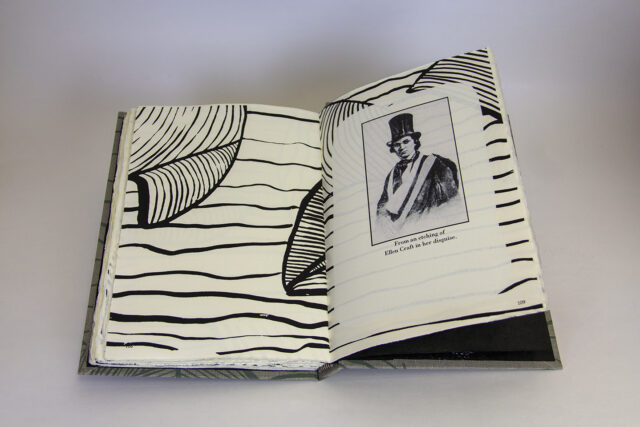

Wrongly Bodied Two relates the stories of Jake, a present-day white man who transitions from female to male, and Ellen Craft, a nineteenth-century black woman, who escapes slavery by passing as a white man. In photographing Jake, Clarissa Sligh explores society’s response to the act of changing one’s identity and re-examines her own fears of crossing the boundaries of gender, race, and class.

Clarissa Sligh, Wrongly Bodied Two, 2004; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

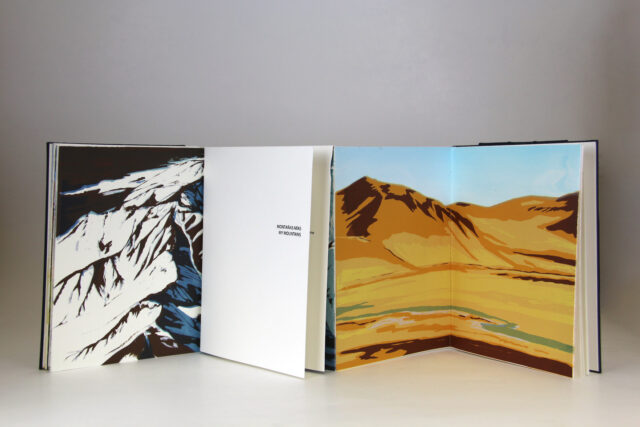

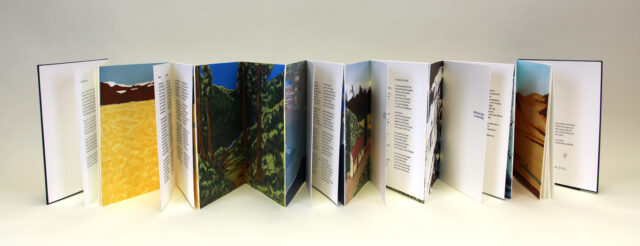

Magdalena Cordero is inspired by the landscapes and writers of her native Chile, particularly the work of Nobel Prize-winning poet Gabriela Mistral. Based on Mistral’s posthumous publication “Poem of Chile,” translated here by Ursula K. Le Guin, this artist’s book was created to introduce the poet’s work to English-speaking audiences.

Magdalena Cordero, Poems by Gabriela Mistral, Translations by Ursula K. Le Guin, Long Chilean Gaia, 2016; Artist’s book; Photo by Emily Shaw, Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

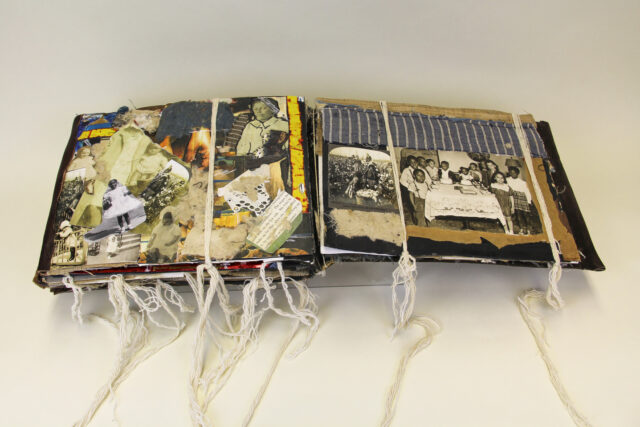

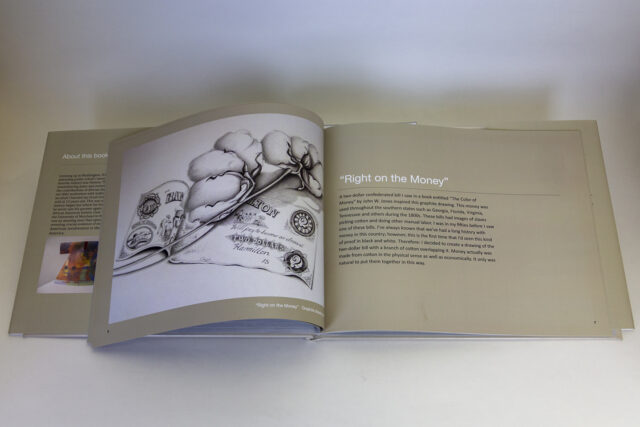

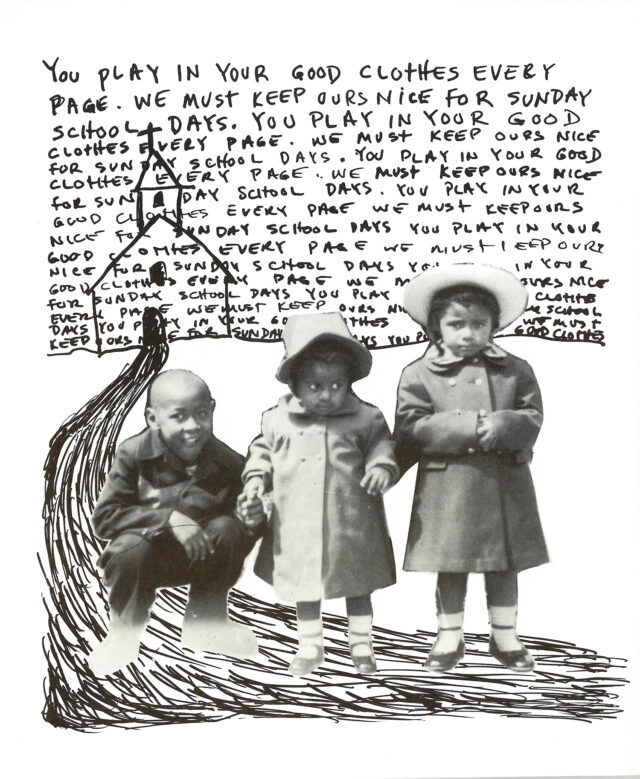

IBe’ Crawley approaches bookmaking as a sculptural practice, describing this piece as a “quilted story.” The artist explores the centrality of cotton farming and processing to African American heritage by depicting its impact on children.

IBe’ Crawley, My Cotton Book, 2010; Artist’s book; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Emily Shaw, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

IBe’ Crawley describes My Cotton Book

“Hi, my name is IBe’ Crawley, and I’m a Storyteller. I created this book called My Cotton Book. It tells the story of children using mixed media collage materials: wool, cotton, leather – lots of cotton – and photographs of children. And showing how they endured many of the hardships of working in the fields, and growing out of that experience and working in factories and being educated and working to overcome the roughness of the slavery experience, even the traumas of slavery, and enduring to the end. In this book, I show the survival of children. It’s called My Cotton Book. My name is Ibe’ Crawley.”

IBe’ Crawley, My Cotton Book, 2010; Artist’s book; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Emily Shaw, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

For Gail Shaw-Clemons, the term “old money” represented a “privileged, untouchable class of people who had no correlation to me, whatsoever,” until she realized the critical role her African ancestors had in “creating the first millionaires in America.”

Gail Shaw-Clemons, Old Money, 2013; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

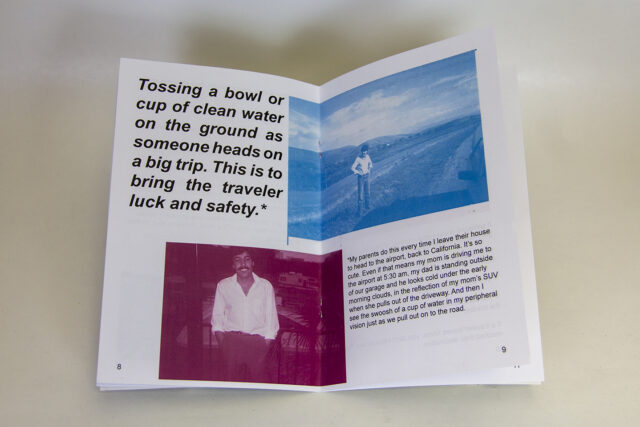

Incorporating stories that the author heard as a child from friends and family, this zine intersperses Afghan superstitions with photos of Sabrina Barekzai’s family from the 1980s. Northern Virginia’s Afghan community is believed to be the second largest in the United States.

Sabrina Barekzai, Afghan Superstitions, Vol. 2, 2016; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

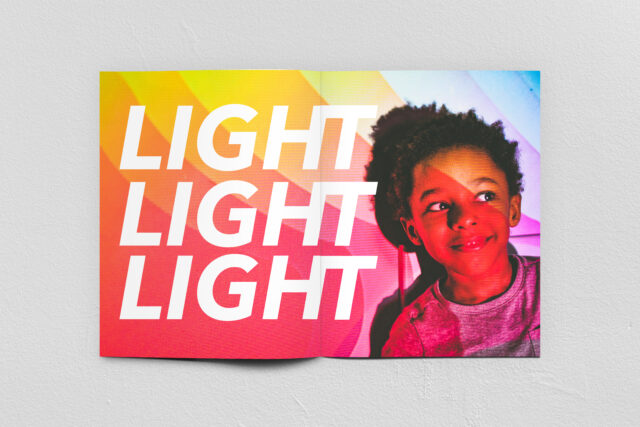

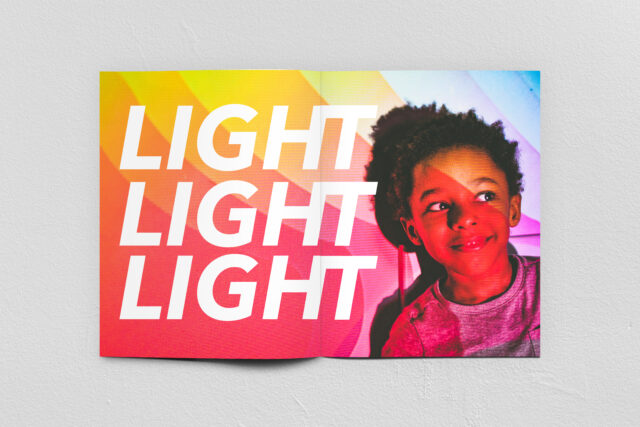

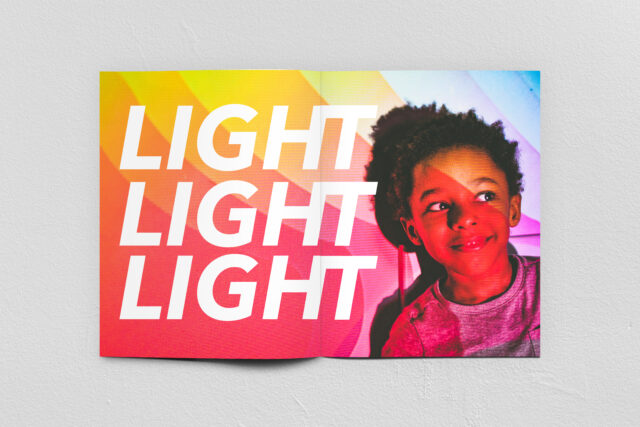

This zine combines text and photographs to celebrate the author’s five-year-old son Knox, who has autism. Jennifer White-Johnson is dedicated to bringing visibility to neurodiversity issues among children of color.

Jennifer White-Johnson with Kevin T. Johnson, Knox Roxs, 2018; Artist’s book; Published by Homie House Press; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Emily Shaw, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Jennifer White-Johnson on Knox Roxs, her art practice, motherhood, and activism

“My definition of mothering as an act of resistance means to redesign anti-racist and ableist visual culture. The sole intention of Knox Roxs is to empower and activate change, encouraging families and communities to engage in conversations about acceptance rooted in how Black autistic children are treated, valued, and seen. When my son was diagnosed as autistic at the age of 2, my role as an artist and mother of a Black disabled child changed. I began exploring how my art and design practice could inform a framework for community engagement, advocating for Black autistics, and examining the erasure of Black disabled children in digital and literary media.” (Transcript continues on the next page.)

Jennifer White-Johnson with Kevin T. Johnson, Knox Roxs, 2018; Artist’s book; Published by Homie House Press; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Emily Shaw, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

“The visual messages I create using languages and photography are reflections of my own thoughts and highlights of conversations within the disability community, which continue to ignite a fire within me to develop anti-racist and anti-ableist media that helps to shift stigmas and advocate acceptance. With art and design at the forefront, I hope to continue breaking the visual cycle of unjust stigmas within the social, creative, and clinical practices within the autism community.”

Jennifer White-Johnson with Kevin T. Johnson, Knox Roxs, 2018; Artist’s book; Published by Homie House Press; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Emily Shaw, Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Robin Ha moved to the United States from Korea at fourteen. This hybrid graphic novel/cookbook contains recipes, colorful illustrations, and information about the basic ingredients found in a Korean kitchen.

Robin Ha, Cook Korean!, 2016; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Hear Robin Ha talk about Cook Korean!

“My name is Robin Ha. I’m the author and the illustrator of Cook Korean!: A Comic Book with Recipes. This book started as a blog called Banchan in Two Pages on Tumblr. Banchan means ‘side dish’ in Korean. Most of the recipes in Cook Korean! are my mother’s recipes, and it is explained through two-page comics. I was born in South Korea, and I’ve been an avid comics reader since I was young. Instructional comics are pretty common in Korea, so the idea to make a comic book cookbook came very naturally to me. Through comics, I want to show how easy it is to make Korean food at home so anyone who likes Korean food would give it a try. I have also included my personal anecdotes and cultural insights in the beginning of each recipe. I hope everyone can enjoy cooking Korean food at home and learn about Korean culture through my book.”

Robin Ha, Cook Korean!, 2016; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

At age fifteen, Sligh was the lead plaintiff in the school desegregation case Clarissa Thompson et. al v. County School Board of Arlington County, filed in 1956, that ultimately granted her the right to enroll at formerly segregated Washington-Lee (now Washington-Liberty) High School in the northern Virginia suburb.

Clarissa Sligh, Reading Dick and Jane with Me, 1989; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

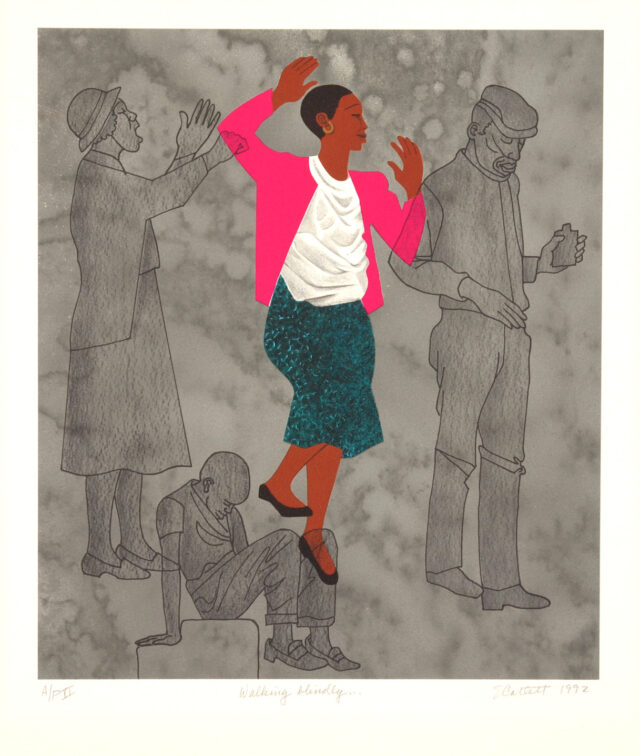

Raised in Washington, D.C., Elizabeth Catlett studied at Howard University under artist Loïs Mailou Jones, whose children’s book illustrations are also included in this exhibition. After receiving a grant in 1946 to work in Mexico, Catlett split her time between New York City and Mexico City, primarily creating prints and sculptures. Her images explore themes of maternity and childhood as well as race, politics, violence, and voice.

Elizabeth Catlett, Walking Blindly, 1992; Lithograph on paper, 22 3/4 x 18 3/4 in.; National Museum of Women in the Arts, Purchased with funds donated in memory of Florence Davis by her family, friends, and the Women’s Committee of the National Museum of Women in the Arts

Many DMV residents are here for a short time, a common scenario for members of military families. Sarah Matthews explores her own experience growing up as a military child, traveling and living without roots. This work, one of a series of three, describes her movement through the DMV, New York City, North Carolina, and Japan.

Sarah Matthews, transient, 2014; Artist’s book; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Emily Shaw, Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

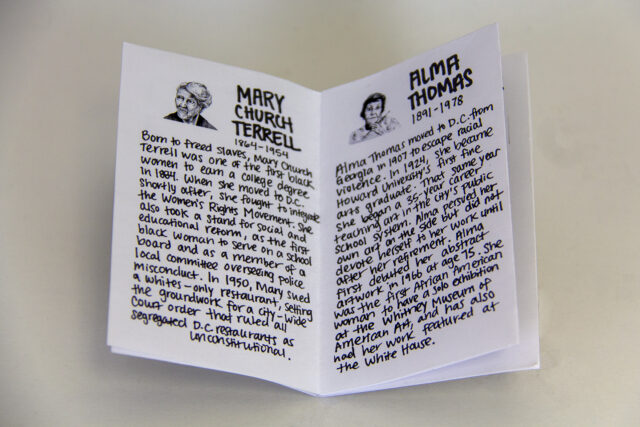

Ruth Tam, a local cultural maven as well as an artist, spotlights short biographies of iconic women from the District of Columbia, including poet Dolores Kendrick and artist Alma Thomas.

Ruth Tam, Women of Washington, 2018; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

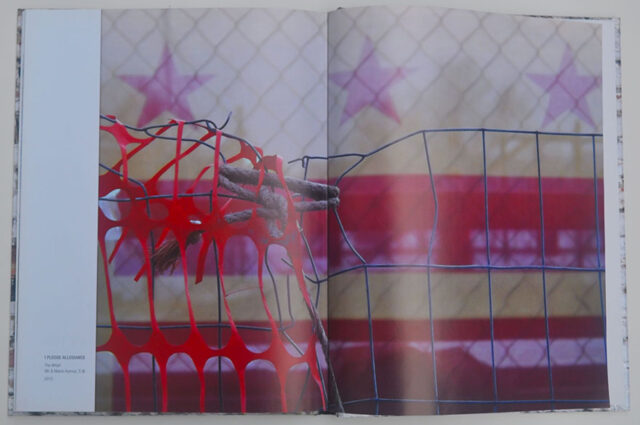

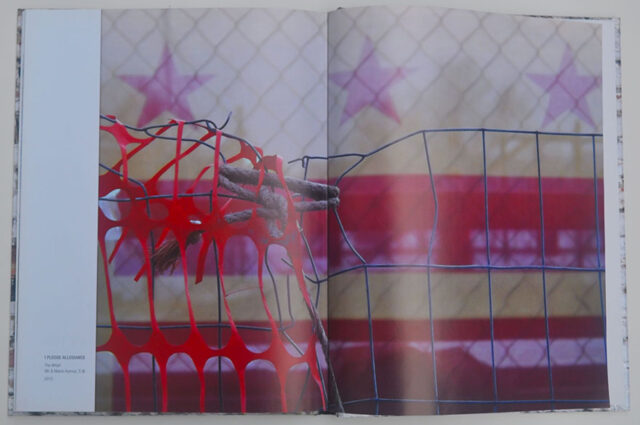

Carolyn Toye deploys her photography of the urban landscape to document the beauty she sees in the city in which she grew up. Through simultaneously realistic and abstract images of a rapidly changing Washington, she preserves city views that some developers have openly vowed to eradicate.

Carolyn Toye, The D.C. I See, 2018; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Carolyn Toye on The D.C. I See and her changing hometown

“I started taking pictures of DC’s architecture and urban landscape in 2004. But less than a decade later, I realized that almost everything I had photographed had disappeared. And because of that, I decided to publish a photo book of my work The D.C. I See: Art of a Vanishing City. Of all the photographs in the book, my favorite is the final image ‘I Pledge Allegiance’ which depicts a faded D.C. flag as the backdrop to a bold orange construction netting. To be honest, there’s a part of me that doesn’t want to like this image because to me it’s a metaphor of DC as the backdrop to all of the redevelopment and gentrification happening across the city. But I have to love this image because I hope that whatever the future holds for this city, this flag and everything that it represents to DC natives like myself will never completely fade away.”

Carolyn Toye, The D.C. I See, 2018; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts

Artists (l-r) Malaka Gharib, Suzanne Coley, Gail Shaw-Clemons, Jamila Felton, Jennifer White-Johnson, Jihae Kwon, and Carolyn Toye at the opening reception for DMV Color at the Betty Boyd Dettre Library and Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, D.C., November 18, 2019.

Photo Credit Alicia Gregory

DMV Color was on view at the Betty Boyd Dettre Library and Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts, November 4, 2019 – March 4, 2020.

All materials presented here courtesy of the Betty Boyd Dettre Library and Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts except:

Elizabeth Catlett, Walking Blindly, National Museum of Women in the Arts, Purchased with funds donated in memory of Florence Davis by her family, friends, and the Women’s Committee of NMWA

Suzanne Coley, All I Have, Courtesy of the artist

IBe’ Crawley, My Cotton Book, Courtesy of the artist

Sarah Matthews, transient, Courtesy of the artist

María Veroníca San Martín, In Their Memory, Courtesy of the artist

Jihae Kwon, A Different Kind of Carousel, 2014; Artist’s book; Courtesy of Betty Boyd Dettre Library & Research Center, National Museum of Women in the Arts