Artists like Mary Evans, Jen Aitken, and Elisabetta Di Maggio, emphasize paper’s ephemeral quality. Despite the transience of their installations, each artist devotes intensive time and skill to creating them, imbuing the act of creating with as much meaning as the resulting works.

Elisabetta Di Maggio, Wallpaper, 2019–20; Tissue paper, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Francesco Allegretto Studio

Mary Evans (b. 1963, U.K. Friends of NMWA)

The silhouetted forms of Evans’s figures are drawn from images frequently found in popular culture. She says, “I want the images to be accessible and rely on them being easily read.” Evans references historical events and their impact on contemporary culture, particularly issues related to the African diaspora. The artist uses Kraft paper to create her works; she has compared its cheapness and disposability, as well as its strength and resilience, to the treatment and survival of Black bodies throughout history.

Mary Evans, Prospect, 2020; Kraft paper and mixed media, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Lee Stalsworth

Jen Aitken (b. 1985, Canada Committee)

Aitken, who frequently works in cast concrete, uses paper to create prototypes for her dense sculptures. However, in Lines+Planes, the prototypes are the end product, enabling Aitken to achieve volume without mass.

Jen Aitken, Lines+Planes, 2020; Paper and mixed media, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist and Georgia Scherman Projects; Photo by Kevin Allen

Aitken constructs her works anew for each exhibition space, and she frequently obscures a complete view of her works by wrapping the geometric constructions around corners and existing architectural elements. In this way, the view shifts based on the observer’s perspective and active participation. Aitken avoids specific interpretations of her work; she emphasizes the viewer’s physical experience of her objects and the space for which they are constructed.

Jen Aitken, Lines+Planes, 2020; Paper and mixed media, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist and Georgia Scherman Projects; Photo by Kevin Allen

Elisabetta Di Maggio (b. 1964, Italy Committee)

Di Maggio likens her practice of repetitively cutting shapes into paper to writing in a diary. Her precise and time-consuming mark-making relates to the laborious and repetitive nature of handiwork, such as embroidery, historically associated with women. Each minute cut records a moment in time and, together, they function as a reclamation and recognition of the unseen labor of women. The delicacy of the tissue paper makes each iteration finite, lasting only as a memory. By expending such time-consuming labor on an ephemeral material, Di Maggio pays homage to the countless forgotten hours of women’s daily activities.

Elisabetta Di Maggio, Wallpaper, 2019–20; Tissue paper, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Kevin Allen

En masse, paper is heavy, unyielding and compact. Angela Glajcar and Dolores Furtado, though varying in scale of their sculptures, rely on the density of the material. While for Sa’dia Rehman and Julia Goodman, paper’s weight is more metaphorical, as they both allude to the medium’s role in recording the weight of history to reinforce the importance of their subjects.

Angela Glajcar, Terforation (detail), 2012; Paper, metal, and plastic, 55 x 39 x 197 in.; Courtesy of K.OSS Contemporary Art; Photo © Angela Glajcar

Angela Glajcar (b. 1970, Germany Committee)

This work is part of a series in which Glajcar hangs sheets of thick cellulose paper in succession, forming compact cubes that float freely in space. The overall geometric structure of Glajcar’s works is interrupted by hand-torn edges that extend into the center of the sheets, creating impenetrable chasms. The view to the other end is always obfuscated, in contrast to the delineated exterior boundaries of the work. The artist’s term “terforation” stems from a combination of “perforation” (making a hole) and “terra,” the Latin word for earth. She also references the idea of “terra incognita,” meaning “unknown land.” In this way, “terforation” refers to Glajcar’s efforts to create enigmatic views through the cavernous voids in her work.

Angela Glajcar, Terforation, 2012; Paper, metal, and plastic, 55 x 39 x 197 in.; Courtesy of K.OSS Contemporary Art; Photo by Lee Stalsworth

Dolores Furtado (b. 1977, Argentina Committee)

For Furtado, the transformation that paper goes through—from raw material to watery pulp, to solidified matter—inspires her to create paper sculptures layer by layer. She works intuitively, each layer determined by the one that preceded it. Furtado likens her process to the organic buildup of sedimentary rocks. As in the natural process, the layers of her work can be examined to reveal the passage of time. Furtado explains, “Every step adds a new layer of information, and the final piece is not a predesigned object, but only the outcome of a series of actions with an open end.”

Dolores Furtado, left to right: Pata (Paw), 2017; Boat, (2018); Desierto (Desert), 2018; Isla (Island), 2019; Morocco, 2018; Paper pulp, 18 x 14 x 3 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Kevin Allen

“As a sculptor, I think of materials as bodies, not as surfaces. The works I’m presenting are pure accumulations of paper pulp… I believe materials carry meaning, and they are spiritually charged. In my world, matter and spirit are the same thing in different forms.” — Dolores Furtado

Dolores Furtado, Morocco, 2018; Paper pulp, 10 x 12 x 3 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo © Dolores Furtado

Sa’dia Rehman (b. 1980, Ohio Committee)

Often used on a smaller scale, stencils are seen as tools employed to replicate text and imagery. In Rehman’s hands, the stencil is enlarged and has become at once a tool and an artwork. Rehman used newsprint to create this image of her family, which is based on a personal photograph. In doing so, she reflects on the way Pakistani Muslim Americans like her family are often portrayed by Western media. Instead of an image of insurgents, victims, or exoticized “other,” the artist presents a simple family portrait. Rehman says, “Continuously smearing ink, smudging charcoal, and shredding paper evoke the circular and violent relationships between history, memory and storytelling, and the self.”

Sa’dia Rehman, Family, 2017; Powdered charcoal on cut newsprint, 96 x 180 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Michelle Burdine

Julia Goodman (b. 1979, San Francisco Advocacy for NMWA)

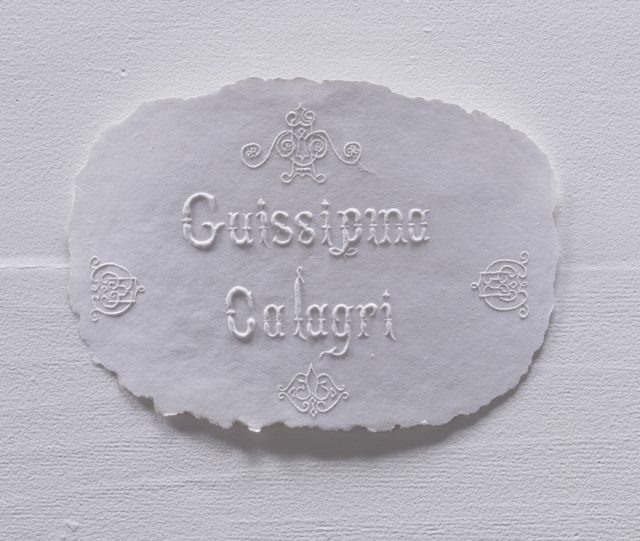

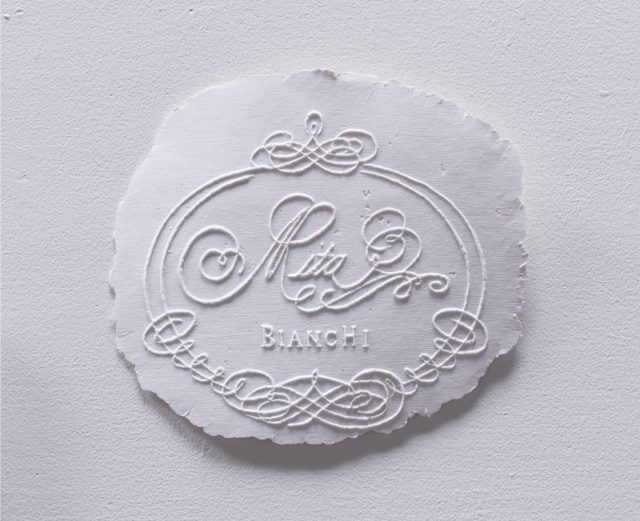

Goodman visualizes the often-invisible labor of women by making her own paper pulp, as well as wooden molds into which she hand-presses the wet material. As part of her sustainable practice, Goodman uses old clothing to make the pulp. In her series “Rag Sorters, 1964,” she memorializes the names of Italian immigrant women who worked to separate discarded textiles from other refuse at a waste management plant in San Francisco during the mid-twentieth century.

Julia Goodman, Rita Bianchi, from the series “Rag Sorters, 1964,” 2013; Pulped fabric, 10 x 11 ½ in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Robert Divers Herrick

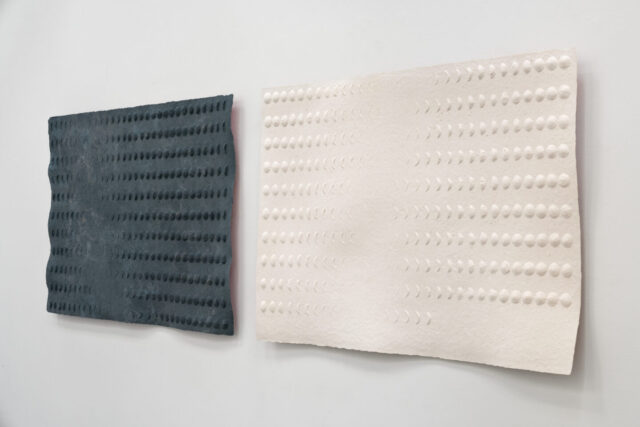

In Waning & Waxing, Goodman records the phases of the moon during the traditional Jewish eleven-month grieving period for her father alongside the length of her pregnancy with her son. She states, “In Jewish tradition, fabric on the chest is ripped at graveside, symbolic of exposing one’s heart in grief. At the conclusion of the mourning period, the rip is sewn and repaired, no longer raw, but leaving a visible scar. By working with handmade paper, I invite contemplation of cycles of love and loss that mark our lives.”

Julia Goodman, Waning (August 19, 2007–July 14, 2008) & Waxing (July 27, 2018–May 10, 2019), 2020; Pulped bedsheets and T-shirts, 33 x 98 x ½ in.; and EUQINOM Gallery; Photo by Phillip Maisel.

Paper cutting is one of the most longstanding traditions in paper art. Along with papel picado of Mexico, paper-cutting practices include silhouettes, developed in eighteenth-century France, and the art of scherenschnitte, or “scissor cuts,” brought to colonial America by German immigrants. Contemporary artists like Georgia Russell, Natasha Bowdoin, Paola Podestá Martí, and Lucha Rodríguez build on this breadth of traditional approaches and reinvigorate the art form in new ways.

Natasha Bowdoin, Contrariwise (detail), 2011; Pencil, gouache, and ink on cut paper, 96 x 96 x 2 in.; Courtesy of the artist and Talley Dunn Gallery

Georgia Russell (b. 1974, Les Amis du NMWA)

Russell creates sculptural works and collages out of used books, musical scores, stamps, maps, currencies, and other found paper sources. Here, she dissects a book, its sliced contents spilling out into a mass of tousled tendrils. Reconstructing historical texts into these new forms allows the artist to ponder their meaning and value in the present day. She says, “Cutting for me is some form of expression and freedom because when you cut something, you’re almost freeing it from what it’s been before.”

Georgia Russell, Attachement (Noir et Pêche) (Attachment (Black and Peach)), 2013; Cut book and Plexiglas, 28 ¾ x 19 ⅝ x 19 ⅝ in.; Courtesy of Karsten Greve Köln, Paris, St. Möritz; Photo by Gilles Mazzufferi

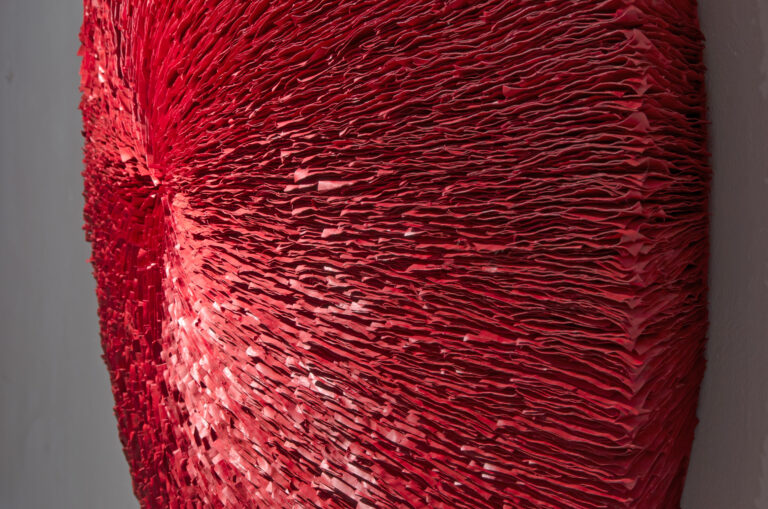

Russell thinks of these compositions as landscape-based works that evoke memories of an image, place, or time. For Red Tide, Russell was inspired by the natural phenomena of harmful algal blooms that at times discolor Florida’s coastal waters with rust-red hues.

Georgia Russell, Red Tide, 2014; Pastel on Kozo paper and Plexiglas, 45 ¼ x 31 ½ x 4 ⅜ in.; Courtesy of Karsten Greve Köln, Paris, St. Möritz; Photo by Gilles Mazzufferi

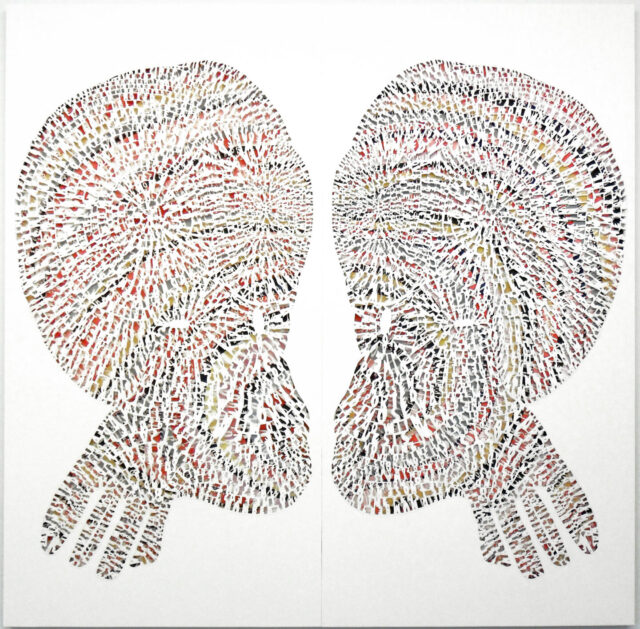

Natasha Bowdoin (b. 1982, Texas State Committee)

Bowdoin transcribes texts from various literary sources, particularly authors she sees as experimental or non-conventional. Contrariwise forms a shallow shadowbox with painted imagery and transcriptions of Tweedledum and Tweedledee’s dialogue in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass. The heads of the two characters manifest from the combination of literary and pictorial elements. Bowdoin painstakingly hand-cuts letters with extreme precision and uniformity. She combines this methodical labor with spontaneity, as the flexibility of paper allows the artist to cut patterns and designs intuitively.

Natasha Bowdoin, Contrariwise, 2011; Pencil, gouache, and ink on cut paper, 96 x 96 x 2 in.; Courtesy of the artist and Talley Dunn Gallery

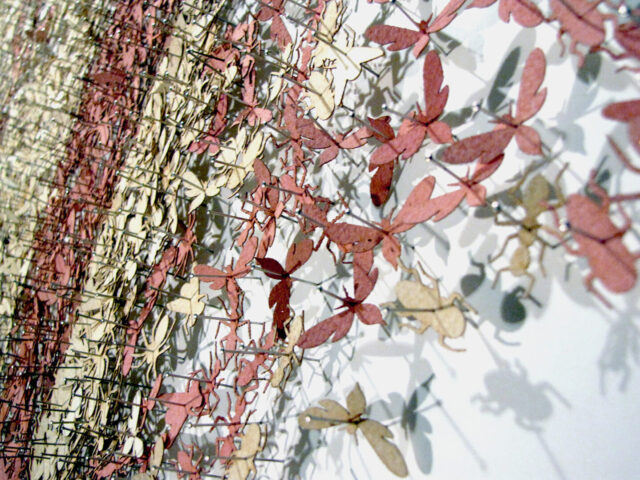

Paola Podestá Martí (b. 1969, Chile Committee)

In this work, Podestá Martí has replicated a portion of the façade of Vergara Palace in Viña del Mar, Chile. The palace was built in 1910 in the Venetian Gothic style by the founder of Viña del Mar, Jose Francisco Vergara. This building, which has been a museum since 1941, has not suffered from neglect, but Podestá Martí alludes to the reclamation of abandoned spaces by nature, constructing her image out of cut-out insects.

Paola Podestá Martí, Vergara Palace Cornice, 2010; Foam core, aquarelle paper, and stainless steel, 82 ⅝ x 118 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Kevin Allen

Podestá Martí uses multiple techniques to create this work, including hand-coloring and laser cutting the paper and hand-assembling the pieces. In this combination of serialized hand work and technological processes, the artist finds a parallel to the industrial production of the early twentieth century (the era that Vergara Palace was constructed), which also relied on both handmade and mechanized elements.

Paola Podestá Martí, Vergara Palace Cornice (detail), 2010; Foam core, aquarelle paper, and stainless steel, 82 ⅝ x 118 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Calipsophotography

Lucha Rodríguez (b. 1964, Georgia Committee)

Rodríguez’s “knife drawings” investigate the ways in which light interacts with paper. The works comprise superficial cuts made with a sharp blade into the surface of the paper and washes of watercolor paint, frequently in shades of pink.

Lucha Rodríguez, Knife Drawing XX, 2018; Watercolor on paper, 30 x 22 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Paco Vergachette

“Each paper has a particular way of interacting with light depending on its fabrication. Some papers absorb light and others bounce it back projecting subtle or heavy shadows, giving unlimited choices and possibilities to be explored.” — Lucha Rodríguez

Lucha Rodríguez, Knife Drawing XX (detail), 2018; Watercolor on paper, 30 x 22 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Paco Vergachette

“Just by showcasing dimensionality, paper can evoke both serene and profound experiences in the viewer. As a medium, it lends itself to be easily manipulated simply with our hands or tools but it is also delicate and needs to be taken care of or it can get ruined by the slightest bend.” — Lucha Rodríguez

Lucha Rodríguez, Knife Drawing XXXVI, 2019; Watercolor on paper, 30 x 22 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Paco Vergachette

One of paper’s distinguishing characteristics is its malleability, providing rich fodder for artistic innovation. Annie Lopez fashions paper dresses to reflect her cultural heritage, Echiko Ohira creates evocative abstract sculptures inspired by forms found in nature, and Dalila Gonçalves produces a cascading textile made of hundreds of sandpaper sheets.

Annie Lopez, Favorite Things (detail), 2016; Cyanotype on tamale wrapper paper, thread, zipper, and metal snap, 46 x 33 x 30 in.; Courtesy of the artist

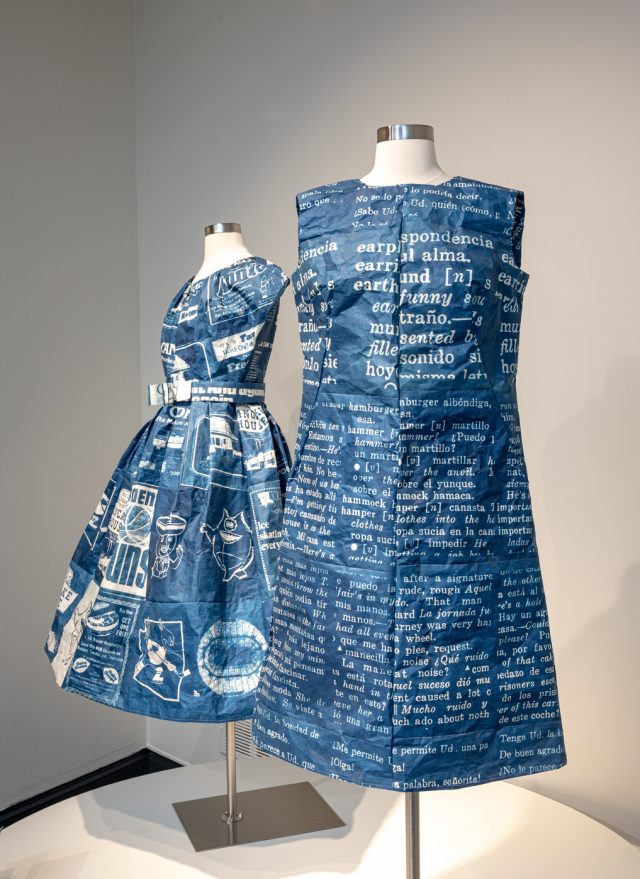

Annie Lopez (b. 1958, Arizona Committee)

The images and text on Lopez’s garments address personal stories of childhood experiences, relationships, as well as the racism and stereotypes she faces as a Latin American woman. After experimenting with different mediums, Lopez began to use tamale wrappers that she found in the “Hispanic foods” section of her grocery store, paying homage to her family heritage.

Annie Lopez, Left to right: Favorite Things, 2016; Cyanotype on tamale wrapper paper, thread, zipper, and metal snap, 46 x 33 x 30 in.; Courtesy of the artist; I Never Learned Spanish, 2013; Cyanotype on tamale wrapper paper, thread, and zipper, 41 x 22 x 9 in.; Courtesy of the artist; The Liberation of Glycerine, 2016; Cyanotype on tamale wrapper paper, thread, zipper, and metal buckle, 51 x 48 x 52 in.; Collection of Eric Jungermann; Photo by Kevin Allen

The signature rich blue hue of the clothes is the result of cyanotype photography, a printing method that involves certain chemical processes paired with the use of UV light. Lopez sometimes stitches together as many as forty sheets of tamale paper to fashion vintage-style dresses, using patterns from the 1960s and 1970s, the artist’s formative years.

Annie Lopez, Left to right: Favorite Things, 2016; Cyanotype on tamale wrapper paper, thread, zipper, and metal snap, 46 x 33 x 30 in.; Courtesy of the artist; I Never Learned Spanish, 2013; Cyanotype on tamale wrapper paper, thread, and zipper, 41 x 22 x 9 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Kevin Allen

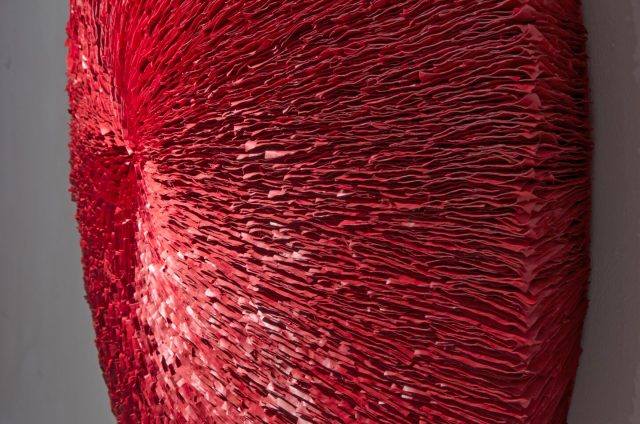

Echiko Ohira (b. 1949, Southern California Committee)

Influenced by the central role of paper in Japanese art and culture, particularly origami traditions, Ohira creates textured, lush paper sculptures that subtly evoke organic forms such as birds’ nests, marine life, and flowers. She states, “I live in the moment and create work. It’s like my diary. Everyday life and all living things become the source of my creativity.”

Echiko Ohira, Untitled (red #4), 2012; Paper, cardboard, acrylic, wire, glue, and wood backing, 50 x 50 x 12 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Gene Ogami

Through labor-intensive techniques, Ohira repeatedly stacks, tears, pleats, coils, glues, and sews layers of untreated, tea-stained, or vibrantly dyed Kraft and recycled paper.

Echiko Ohira, Untitled (paper and thread #3), 2016–17; Tea-stained blueprint, cardboard, thread, and glue, 39 x 39 x 11 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Gene Ogami

Dalila Gonçalves (b. 1982, Portugal Committee)

Gonçalves worked with a group of people from her hometown in Portugal to soak approximately 240 sheets of blue sandpaper, removing the layers of grit through a time-consuming and labor-intensive process. She sutured the stripped sandpaper sheets into an expansive patchwork of various blue hues that drapes from the ceiling to floor. The artist also collected and molded the loose sediments into a hardened form, creating the nearby blue sphere. Gonçalves’s method transforms one material into another—paper into fabric and stone—reversing the industrial process used to create sandpaper.

Dalila Gonçalves, Desgastar em Pedra (segundo ensaio) (To Wear in Stone (second test)), 2018; Blue sandpaper and agglomerated sand, approx. 157 ½ x 78 ¾ x 70 ⅝ in.; Courtesy of the artist and Galería Rafael Ortiz; Photo by Kevin Allen

Paper’s adaptability allows a multitude of techniques in addition to cutting. Joli Livaudais applies the art of origami to her practice while Hyeyoung Shin draws on Jiho-gibeop, a traditional Korean method of paper casting from objects.

Hyeyoung Shin, Tide (detail), 2019–20; Cast Gampi paper, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Aaron Paden

Joli Livaudais (b. 1968, Arkansas Committee)

Livaudais prints photographs of personal subjects—family, friends, artwork, and objects of beauty for the artist—and shapes them into scarab beetles, which appear in her work as symbols of spiritual transformation. A site-specific installation, All That I Love may comprise more than 1,800 beetles. The time-consuming physical process of folding each photograph fosters the artist’s personal meditation on past experiences.

Joli Livaudais, All That I Love, 2012–present; Photography on Kozo paper, aluminum, epoxy resin, and pins, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Lee Stalsworth

“Reduced to their elemental parts, the photographs become merely paper. The remnants of the memories they represent are glimpsed only in fragments of sparkling color on the backs of the beetles they have become.” — Joli Livaudais

Joli Livaudais, All That I Love (detail), 2012–present; Photography on Kozo paper, aluminum, epoxy resin, and pins, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist; Photo © Joli Livaudais

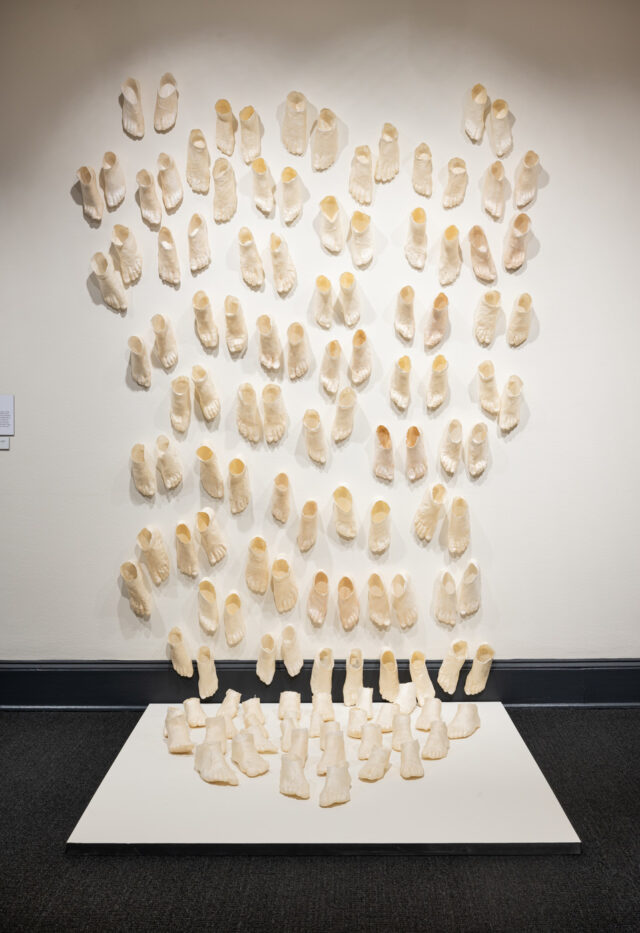

Hyeyoung Shin (b. 1973, Great Kansas City Area Committee)

Shin uses Jiho-gibeop, a traditional Korean method of paper casting from objects that is similar to papier-mâché. In Tide, inspired by the worldwide Women’s March rallies in early 2017, Shin casts individuals’ feet to reflect on the distinct and collective paths that people take as a result of personal and political values. The thin paper, made from durable, yet translucent fibers of Gampi bark, enables the artist to replicate the precise contours and structures of the skin and bones. Shin continues to produce paper casts for Tide in Paper Routes, there are more than sixty pairs installed, the largest iteration of this work to date.

Hyeyoung Shin, Tide, 2019–20; Cast Gampi paper, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Kevin Allen

At the turn of the twentieth century, artists experimented with and explored the practice of collage, a term derived from the French word coller or “to glue.” Contemporary artists like Mira Burack, Luisa Pastor, and Elizabeth Alexander expand the technique’s traditional boundaries.

Luisa Pastor, El azar del mestizaje: Negro/Azul (The Chance of Miscegenation: Black/Blue) (detail), 2016; Mexican National Lottery tickets, 33 ⅝ x 37 ¾ in.; Courtesy of Galería Nordés; Photo by Antonio Seva

Mira Burack (b. 1974, New Mexico Committee)

Burack reflects on beds and bedding to contemplate ideas about the subconscious and the mind at rest. She collages and layers hundreds of photographs of bedding to create the illusion of three-dimensional space. Calming, muted color palettes and perceived softness from the images of bedding create a material language that connects to her themes of sleep and healing.

Mira Burack, Sun (son), 2015; Photography collage and paint, 84 in. diameter; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Eric Swanson

“I consider the bed a rich, contemplative site to consider materials, relationships, and our experience of rest in a swiftly-paced 21st-century. The inherent qualities of paper—its flexibility, its sheen, its ability to be cut and manipulated, its bridging of 2D and 3D…make it a primary and magnetic material for this work.” — Mira Burack

Mira Burack, (dark) Waterdrop, 2018; Photography collage and paint, 45 x 36 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Eric Swanson

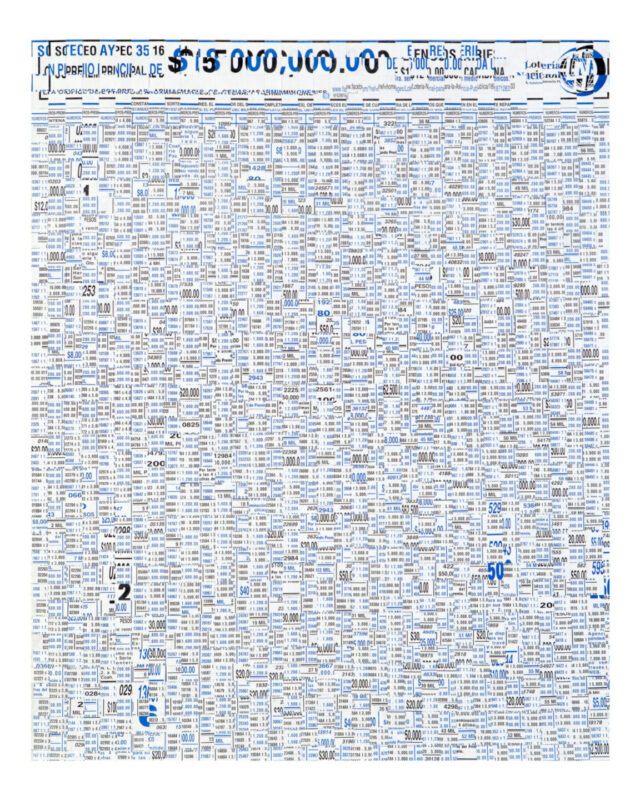

Luisa Pastor (b. 1977, Spain Committee)

Pastor reflects on the histories of miscegenation by interweaving lottery tickets of different colors—black and yellow or black and blue—into new compositions. Perhaps an analogy for human genetic material, this “reconfiguration of the physiognomy of the lottery sheet” poetically subverts the concept of racial hierarchies through random mixing.

Luisa Pastor, El azar del mestizaje: Negro/Azul (The Chance of Miscegenation: Black/Blue), 2016; Mexican National Lottery tickets, 33 ⅝ x 37 ¾ in.; Courtesy of Galería Nordés; Photo by Antonio Seva

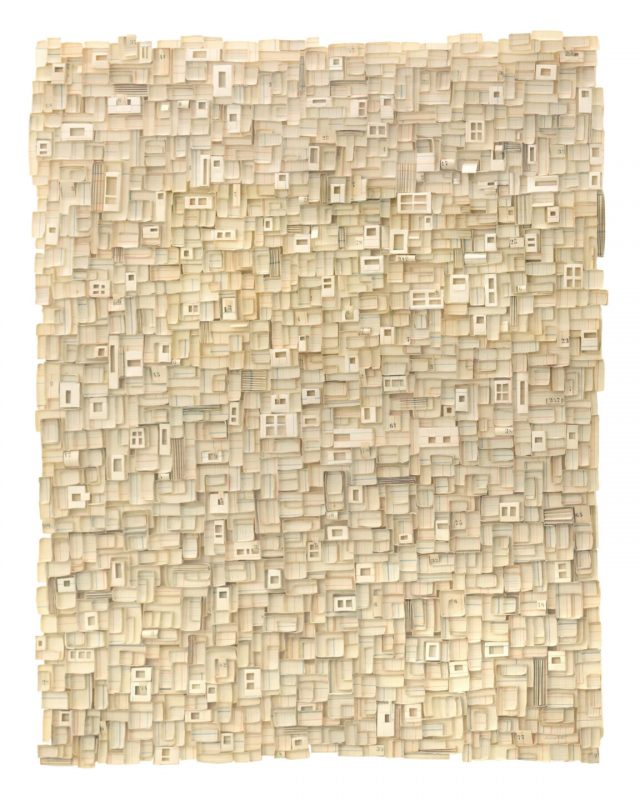

The artist deconstructs societal values and ideas while creating new meanings by bringing together fragments of old accounting books, journals, and other common objects. Discussing her choice of materials, Pastor says, “I have always been drawn to working with papers I find in flea markets or antiques stores because I am interested in rescuing the traces of time imprinted on paper.”

Luisa Pastor, Topología del pliegue (Topology of the Fold), 2018; Accounting book papers, 43 x 32 ⅞ in.; Private collection, Munich

Elizabeth Alexander (b. 1982, Massachusetts Committee)

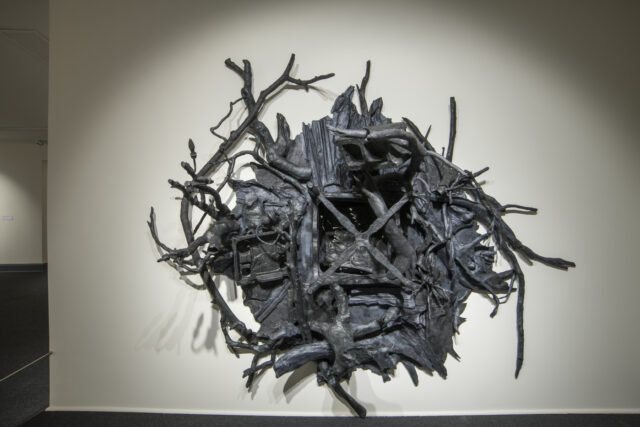

Aided by precise cutting tools, Alexander casts and assembles paper objects into whimsical and imposing sculptural collages. The artist uses a laminate casting method, which results in hollow sculptures made of thin paper. Alexander was inspired to create All Things Bright and Beautiful while working in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, observing charred residue that remained a year after the devastating wildfires in 2016. The work’s two sides are connected by the void space of the wall in between. For the colorful side, Alexander carefully extracted thin layers of patterns from floral wallpaper, which she applied to the cast objects.

Elizabeth Alexander, All Things Bright and Beautiful (side 1), 2019; Cast paper and extracted wallpaper pattern, 92 x 124 x 40 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Lee Stalsworth

The dark, sinuous branches on the blackened side evoke burnt debris from the fire. Alexander uses her meticulous art to work through personal challenges, sharing, “Repetitive labor, such as paper cutting or casting, has become a centering element within my practice to work through frequent moments of illness or stress.”

Elizabeth Alexander, All Things Bright and Beautiful (side 2), 2019; Cast paper, 95 x 124 x 30 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Lee Stalsworth

For centuries, drawing on paper has been at the core of artistic training and practice. Some artists included in this exhibition incorporate hand-drawn elements into their work, while also manipulating the paper itself. Rachel Farbiarz likens her cut elements to her drawing process: both require dexterity and control. Natalia Revilla uses drawing to create a tromp l’oeil effect that obfuscates reality between the image and the physical surface of the paper. And drawing is an accretionary act for the work of Oasa DuVerney, who vigorously applies graphite to her cut paper.

Oasa DuVerney, Black Power Wave: Drawing for Protest (detail), 2017; Graphite and neon ink on paper, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Welancora Gallery

Rachel Farbiarz (b. 1977, Mid-Atlantic Committee)

Using a combination of her own drawing and precisely cut-out images extracted from vintage books, Farbiarz creates vignettes that reveal ironies of the human condition. While not a narrative account, this scene is inspired by the so-called “Christmas Truce” during World War I, when British, French, and German soldiers informally halted their warfare in order to celebrate Christmas together.

Rachel Farbiarz, Memorial Hill, 2013; Graphite and collage on paper, 31 ½ x 71 ¾ in.; Collection of Tobie Whitman and Daniel Yates; Photo by Greg Staley

Farbiarz captures the situation’s absurdity through a seemingly festive tableau, replete with banners, ribbons, flowers, and flags. Further inspection reveals disturbing details like artillery and prone bodies on the ground. Farbiarz notes, “We indulge in beauty and pomp, ceremony and delight—even as we, again and again, destroy and violate.”

Rachel Farbiarz, Memorial Hill (detail), 2013; Graphite and collage on paper, 31 ½ x 71 ¾ in.; Collection of Tobie Whitman and Daniel Yates; Photo by Greg Staley

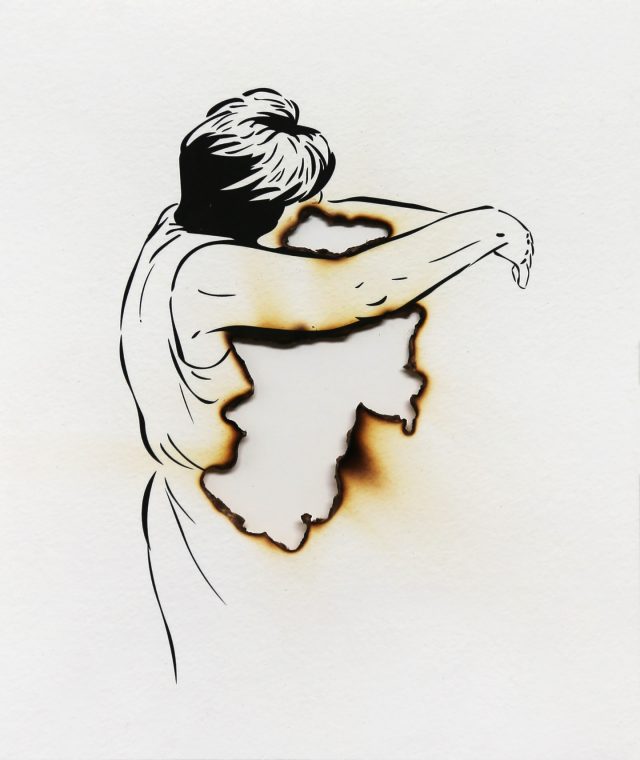

Natalia Revilla (b. 1981, Peru Committee)

Revilla bases her images on personal photographs as well as photojournalistic imagery of political unrest in Peru. She juxtaposes hand-drawn images with voids created by carefully burning paper away, raising questions about the interdependent processes of creation and destruction. Entirely new narratives result from the drawn image and the visceral destruction of the paper, independent of the original photographs.

Natalia Revilla, Untitled, from the series “Quemados” (“Burned”), 2011; Mixed media on burned paper, 7 ½ x 6 ¼ in.; Courtesy of the artist

In these hand-drawn and embossed works, Revilla reflects on the possibilities and limitations of language to connect people. Here, she offers visual definitions of words in the Machiguenga languages that have no direct translation into Spanish. The Machiguenga are an Indigenous group of people who live in the Amazonian jungle of southeastern Peru. Revilla states, “There is a real need to communicate [between the Spanish-speaking government and Indigenous groups], but dialogue is effectively impossible. Communication should not be understood solely within the context of its linguistic function, but rather as a political and cultural instrument, an act of communication in a given cultural context.”

Natalia Revilla, Apipakotene, from the series “Veinte palabras” (“Twenty Words”), 2016; Ink on embossed paper, 21 ⅝ x 15 in.; Courtesy of the artist

Oasa DuVerney (b. 1979, New York Committee)

Inspired by the gathering of individuals to speak out against social injustices, DuVerney’s work functions literally and figuratively as a drawing for communal protest. When disassembled, each individual placard is an equal part of the collective whole. As it comes together, DuVerney explains, the powerful wave “immerses the viewer in the experience of Black power and identity while denying the exploitation of our [Black] bodies.”

Oasa DuVerney, Black Power Wave: Drawing for Protest, 2017; Graphite and neon ink on paper, dimensions variable; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Kevin Allen

Paper Routes—Women to Watch 2020 is organized by the National Museum of Women in the Arts and sponsored by the participating committees. The exhibition is made possible by Northern Trust with additional funding provided by the Clara M. Lovett Emerging Artists Fund and the Sue J. Henry and Carter G. Phillips Exhibition Fund. Further support is provided by Bayer AG, the Council for Canadian American Relations, Luso-American Development Foundation, and the French-American Cultural Foundation.

Echiko Ohira, Untitled (red #4), 2012; Paper, cardboard, acrylic, wire, glue, and wood backing, 50 x 50 x 12 in.; Courtesy of the artist; Photo by Gene Ogami