Incompetence Exacerbated by Malevolence

The coronavirus has dangerously inverted a long-standing White House theme.

Throughout the many disasters that have befallen the Trump administration, one theme has remained a constant: malevolence tempered by incompetence. That description emerged from a text-message conversation between the two of us in January 2017, the day after the release of the president’s first travel ban. Chaos was erupting at ports of entry around the country. U.S. permanent residents were being denied entry. Courts were getting involved. Protesters and lawyers were assembling at airports. And yet, the worst consequences were averted, because the travel ban was so ineptly conceived and executed that it was quickly put on hold and later substantially rolled back.

The phrase took on a life of its own, because so many other events of the past three years followed a similar pattern. The New York Times columnist Paul Krugman used it to describe the botched Republican effort to undo the Affordable Care Act. Senator Ed Markey pointed to it in condemning the administration’s failure to care for immigrant children separated from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border. Describing the president’s slapdash trade policy, the podcaster Mike Pesca suggested that a better formulation might be “malevolence tempered by incompetence shot through with mendacity”—emphasizing the pervasiveness of Donald Trump’s lies in the conduct of his administration.

Now, however, the disease known as COVID-19 has upended this theme altogether. As the former Justice Department official Carrie Cordero declared on Twitter: “To invert a @benjaminwittes formulation, the Trump administration #COVID19 response might be characterized as incompetence exacerbated by malevolence.”

It is an inversion in more ways than one. In the original formulation of the phrase—malevolence tempered by incompetence—the incompetence not only comes second, but it mitigates the malevolence. In Cordero’s rather apt reformulation, by contrast, the incompetence comes first, and the malevolence doesn’t mitigate it. It makes things worse.

The “incompetence” portion of the current situation is all too easy to identify. A February 28 ProPublica report describes how the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention “lost valuable weeks that could have been used to track [the coronavirus’s] possible spread in the United States,” because the agency insisted on developing its own tests for the virus instead of adopting those provided by the World Health Organization.

Then the CDC-developed tests proved to be unreliable, setting the agency back in its effort to enable widespread testing and squandering precious time needed to prepare for the virus’s arrival. On top of that, early federal guidance provided only for testing of people returning from international travel—and even after those restrictions were loosened, story after story surfaced of potential COVID-19 patients who had been denied testing despite their symptoms. Private labs and companies have only recently been allowed to run tests. As a result, only about 4,300 people in the United States had been tested for the virus as of March 9. Compare this with South Korea’s numbers, which total as many as 10,000 people tested a day.

Widespread testing is crucial for preparing for and limiting the spread of an epidemic like COVID-19. According to Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the federal government may have finally ironed out the difficulties: He announced on March 8 that “around 4 million” tests would be sent out by “the end of next week.” But while it’s good news that the U.S. is catching up, most public-health experts agree that the delayed start has created a serious public-health challenge. Irwin Redlener, a physician who studies public health and disaster preparedness at Columbia University, condemned the federal government’s response as “the most egregious level of incompetence in an administration that I think we’ve witnessed at least in my memory … It’s actually stunning.”

How much of the incompetence is Trumpian incompetence, and how much is composed of lower-level screw-ups that can’t be laid at the president’s door? That’s unclear. But as Lisa Monaco, who managed the United States’ response to the 2014 Ebola crisis as chief homeland-security adviser, wrote recently, the Trump administration has eliminated the government positions that the Obama administration created to address pandemic disease: “In 2018, [the key] unit was dismantled and its career expert leader reassigned. Today, there is no dedicated unit within the [National Security Council] to oversee preparedness for pandemics or the current response to the coronavirus.” In other words, even if the incompetence is not coming directly from the president, it originates in the administration’s general disorganization and disrespect for the orderly working of government. And the president hasn’t seemed especially focused on maximizing an efficient government response.

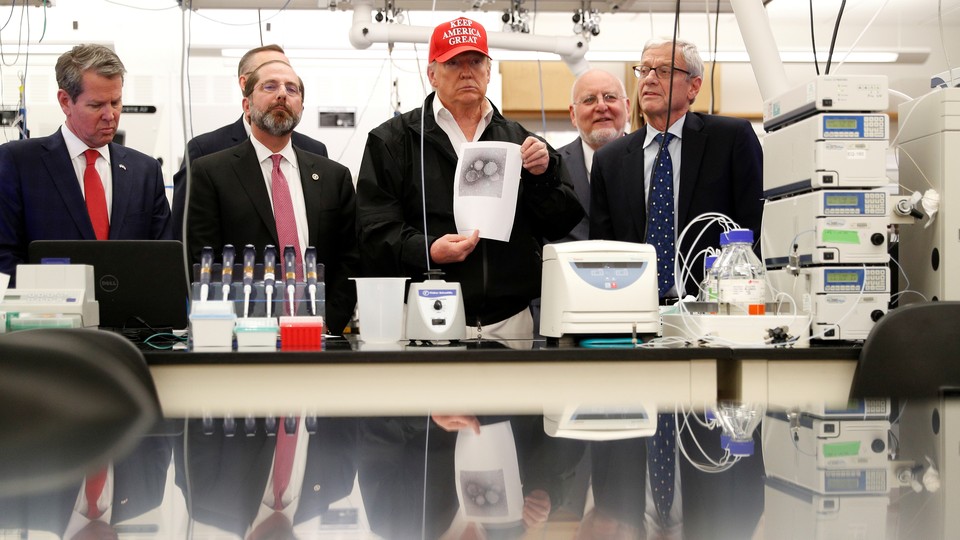

Which brings us to the malevolence. President Trump’s statements since the virus first appeared in the United States have been wholly untouched by concern for anything except blame avoidance. “We have a perfectly coordinated and fine tuned plan at the White House for our attack on CoronaVirus,” he tweeted Sunday morning. “We moved VERY early to close borders to certain areas, which was a Godsend. V.P. is doing a great job. The Fake News Media is doing everything possible to make us look bad. Sad!” At the CDC on March 6, he declared the coronavirus tests “perfect”—like his call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, which ultimately led to Trump’s impeachment: “The tests are all perfect, like the letter was perfect. The transcription was perfect. Right? This was not as perfect as that, but pretty good.”

Trump has tried to bully the stock market, even as he has tried to minimize the risk posed by the virus, suggesting that the pathogen would take care of itself with warmer weather, that it was little more than the flu, or that people might safely go to work when infected. He barely bothers to express concern about public health, choosing instead to wax indignant about how the virus is affecting his public image. This has led to some scenes that might have been bleakly funny if not for the many lives at stake. At the Conservative Political Action Conference in February, then–White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney downplayed the threat of the virus and insisted that critical press coverage was aimed only at harming the president; a week later, reports emerged that a conference attendee who shook hands with Senator Ted Cruz had tested positive for the virus.

Whether or not malevolence generates incompetence in any particular instance, it drifts about like an obfuscating fog. The result is that knowing whether the administration’s decisions derive from malevolence, incompetence, or both becomes impossible—as does trusting any given statement made by the White House about the crisis. The administration, for example, might have had a good reason to veto the CDC’s proposal recommending that older people and those with medical issues cease flying on commercial airlines. But the White House has provided no reason to trust that this decision wasn’t purely political, clumsily aimed at minimizing panic at the cost of public health.

In our column last week, we noted that Trump’s normal playbook is particularly ill-suited to a crisis in which nobody is to blame, involving an adversary who cannot be bullied and against which competent crisis management offers the only plausible hope for success. The Chinese Communist Party did incalculable damage to world public health with its early strategy of lying and denial. Crucial time to contain the virus was lost. Early chances to protect people through commonsense social-distancing measures were lost as well. It was easier in the short term for the party to lie, cover up, and deny than to lose face by allowing the outbreak to become publicly known.

In a true disaster, the malevolence never successfully covers up the incompetence. It can do so for a while. But the disaster is ultimately uncontainable.

This past spring, HBO aired a timely miniseries dramatizing the 1986 nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl. There is a great deal of difference, of course, between Chernobyl and an pandemic. But one early scene from the series is particularly resonant: The chief engineer of the power plant is informed that a nuclear reactor has likely exploded. Instead of listening to his worried employee, he screams that the man is mistaken and that the evidence of the explosion isn’t real. Minutes later, the chief engineer vomits and loses consciousness—poisoned by a massive dose of radiation.

Trump is making a similar error now to the one the Chinese government made a couple of months ago and to the one HBO portrays the chief engineer at Chernobyl as having made. The president can’t pretend the virus does not exist. He can’t suppress news of it, unlike the Chinese Communist Party or the Soviet government in 1986. But he can berate those who report on it honestly. He can deny its severity. He can lie about it—all until the moment at which he can’t anymore, the moment at which the malevolence no longer covers up the incompetence but amplifies it, at great human cost.