Fifty years ago, Marion Brown recorded “Afternoon of a Georgia Faun,” an experimental, musical collaboration to re-create the sounds of nature from his Southern childhood. Jazz critic Jon Ross takes us on a journey through Brown’s musical legacy.

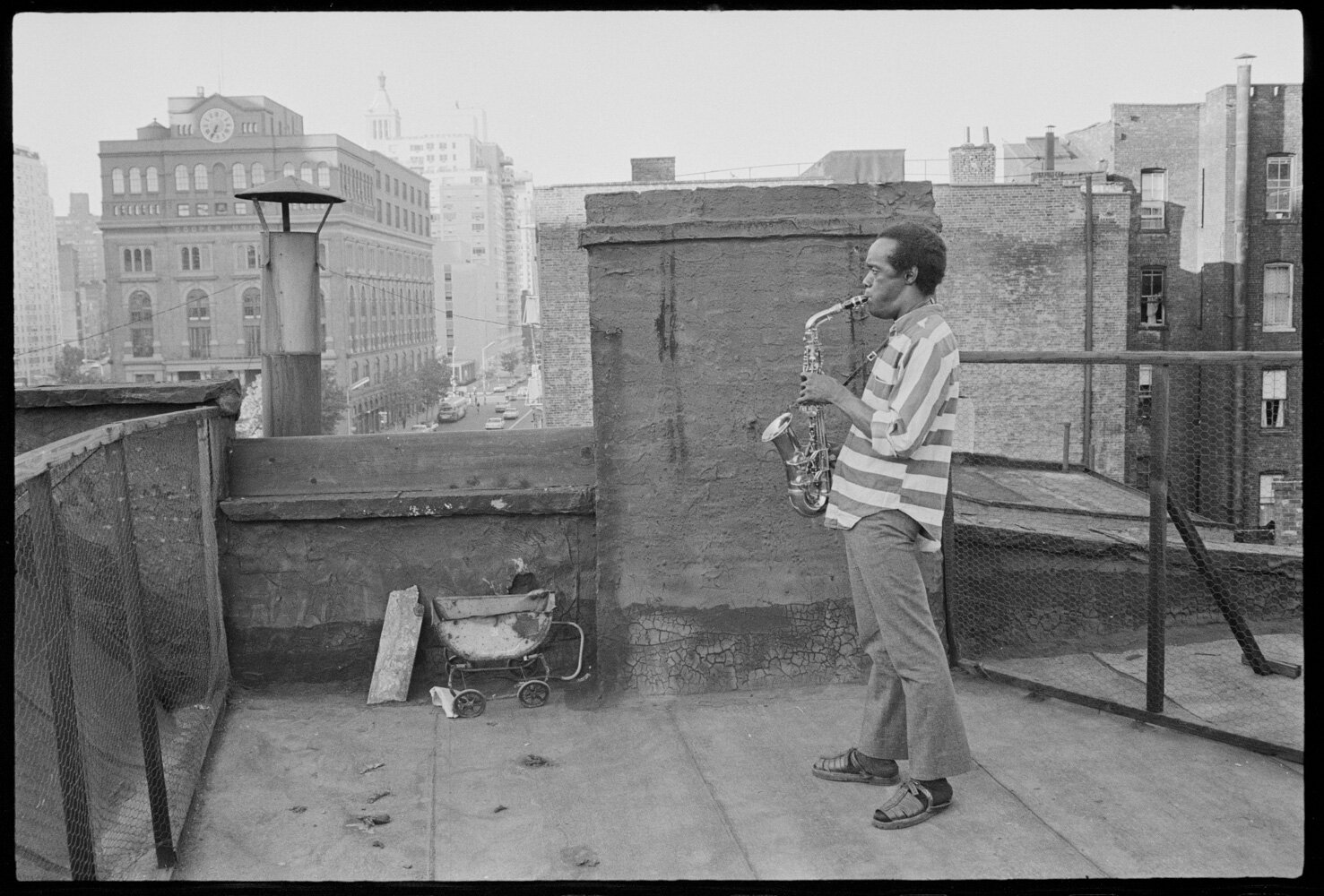

Story by Jon Ross | Photographs by Larry Fink

In memory lie the seeds of improvisation; in technique, the means by which to cultivate the memory, nourished by both tradition, in the form of myths, and by whatever science is available, even if it is called religion or magic.

— Marion Brown, “Notes to Afternoon of a Georgia Faun: views and reviews,” 1973

Decades removed from his boyhood in 1930s Atlanta, Marion Brown, a free-thinking saxophonist who cut his teeth with inquisitive jazz musicians like John Coltrane and Sun Ra, still kept his childhood close. From Washington, D.C., to New York to Paris, he carried impressions, suspended sights and sounds: the crunch of gravel underfoot as he strolled with his German shepherd through his southwest Atlanta neighborhood; the smooth-shelled pecans he collected from the ground on the way to school, magnolia and honeysuckle perfume permeating the air.

His grandfather, a healer, created herbal remedies. Later in life, Brown recalled earthy, heady fragrances wafting through the house from boiling pots filled with roots and twigs. Congregational hymns, led by the organist at Flipper Temple A.M.E. Church, filled his ears on Sunday mornings.

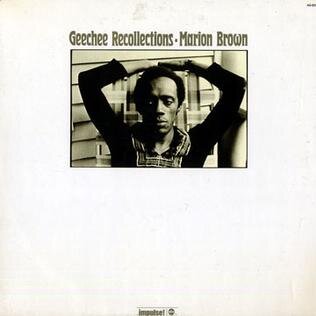

Brown lived through his early teens in the alleys of West Fair Street, now the heart of the Atlanta University Center Historic District; in nearby woods; and at his uncle’s house in rural north Georgia. His memories would become the basis for a seminal recorded recollection of home, a three-volume abstract study of Southern sounds that began with ECM Records’ release of “Afternoon of a Georgia Faun” in 1971. The next two installments, “Geechee Recollections” and “Sweet Earth Flying,” followed in 1973 and 1974 on Impulse! Records. Produced as separate albums, they coalesce into a Georgia trilogy, a narrative of memory, amplified by Brown’s research into ancestral African music.

A lifelong academic and trained ethnomusicologist who received a master’s degree in the subject from Wesleyan University in 1976, Brown applied a nascent thirst for knowledge in mapping out the recordings. In his trilogy, the sparse and abstract percussive “afternoon” leads into a song collection celebrating the Geechee culture of coastal Georgia, ending with the diaphanous, colorful wash of nostalgia and the sound of home.

Brown rose to renown playing the alto sax in New York’s fertile “new music” improvisation scene of the 1960s, but his series of impressionistic, inscrutable albums based on his birthplace are vastly different sonically from those early explorations. This year, on the 50th anniversary of “Georgia Faun,” Brown would have turned 90; he died in Florida in 2010.

Marion Brown’s memories of his Georgia childhood would become the basis for a seminal recorded recollection of home, a three-volume abstract study of Southern sounds that coalesced into three separate albums: “Afternoon of a Georgia Faun,” “Geechee Recollections,” and “Sweet Earth Flying.” Photos by Larry Fink.

Many of the musicians on these recordings became his lifelong friends, and Brown sought out mentors even as he assisted younger players. At 30, he played the worldly elder to the 20-something musicians who saw in him a deliberate, quiet man. Clean cut and with an air of solemnity, he always appeared nattily put-together in public. (Before the public debut of Harold Budd’s “Bismillahi 'Rrahmani 'Rrahim,” Brown told the composer, “You have to look pretty to play pretty.”)

“He was a friendly, warm person, but he didn’t do a lot of talking,” recalled Amina Claudine Myers, the pianist who, in 1979, recorded her debut album using Brown’s deceptively simple piano compositions. “He was a lot of fun. He wasn’t distant, but he just didn’t talk or say much.”

Above all, Brown was a somber, private person, according to longtime collaborator Wadada Leo Smith.

“You find very few photos of Marion where he’s laughing and throwing his hands up and having great fun,” Smith said. “When you see him, he’s looking very serious, straight out at you.

“He managed the economy of how you live and how you associate and socialize with people. He was a very dignified person. He came from the South; he understood, you know, the dynamics of social relationships.”

The title track on “Georgia Faun” is not about the notes played or the facility of each performer; Brown didn’t even pick up his saxophone during the 17-minute tune, but the ideas, the organization, and the feeling are his own. In fact, nearly all of the musicians on the record stayed away from their primary instruments. Brown played a zomari, a Tanzanian double reed instrument, and various forms of percussion; saxophonists Anthony Braxton and Bennie Maupin can be heard on wooden flutes, evoking birds and woodland life. The emotive quality of the sounds is paramount. Brown hewed to this concept throughout the trio of records.

Brown catalogued the sound world of “Georgia Faun,” describing experiences and memories from his childhood. “Things that I saw and heard each day going from my house to school, church, visiting, roaming with my dog and a BB gun looking for birds to shoot. We cooked them over open fire in thick patches of woods near where I lived,” he said in an interview for 1973’s “Notes to Afternoon of a Georgia Faun: views and reviews.”

“It was also,” he continued, “the things my ears enjoyed: birds singing outside my window, dogs barking, a rooster crowing in the morning, crickets in the summer, the sound of people having a good time in one of the houses where those good times are had, standing outside the sanctified church at night enjoying music, and the sound of happy feet stamping furiously, in tune with the preacher and themselves.”

Rain arrives in the afternoon. The storm begins as a sprinkle — slow taps on a woodblock mimic fat, lazy raindrops, a contrast to the pop-up downpours that pass transiently through endless Georgia summers. This shower builds rhythmically, as more members of the band take up percussion, developing into a torrent, amplifying a timberland cacophony. The sounds of running water, mouth clicks, and pops, whistles and tuneless humming drift through the space, amplifying the sense of vast, unexplored nature.

The cleansing rain clears, and other sounds blur into this aural landscape. A melancholy keyboard melody drifts through, the pianist scraping across the strings, playing the guts like an ominous, sylvan harp. The ephemeral melody devolves into disjunct smears of sound. Now come the approaching-night noises. Dulled bells and whistles echo thick and humid. Clicks and pops reverberate. Water flows. Chirps, wordless vocalizations, and percussion commingle as the dense, confounding sound of nature’s discourse.

“Afternoon of a Georgia Faun,” woodcut by Michael Kelly Williams, 1982.

The music came together in the cramped Sound Ideas Studio in New York City, some 850 miles from his boyhood home, where a group of noted instrumentalists recorded two completely improvised tunes following loose structural guidelines. Nothing was written down. Braxton and Maupin; vocalists Jeanne Lee and Gayle Palmore; pianist Chick Corea; drummer Andrew Cyrille; bassist Jack Gregg; and a handful of novice percussion players, dubbed “assistants,” had heard Brown’s concept for the session during rehearsals in an apartment within the Westbeth Artists’ Housing. For the four-hour recording session, the musicians channeled his memories, recording two takes of the title track and a single run-through of the playful, chaotic “Djinji’s Corner.”

In the liner notes, Brown sets out his vision plainly, calling his work a “tone poem” depicting nature in and around Atlanta. The “quiet and calm” of the title piece, about which Brown wrote in his 1976 thesis, give “the impression of being alone or suspended in time and space.”

The pianist, arguably the focal point of the tune, had met Brown briefly during a get-to-know-you session months earlier. Fifty years later, Corea doesn’t remember the specifics of the recording process but recalls the feeling of being in the room that day with the other musicians.

“There was so much respect for one another in the studio that … as soon as the first sounds began and we knew we were recording, everyone was in it and totally listening to one another — listening to the sounds that the others were making and always putting something in that complimented the other sound or contrasted the other sound one way or the other,” Corea said. “That was the vibe, and it was very thick and very pleasurable.”

As a drummer, Cyrille’s duty during the recording was to listen to the horn players and accentuate the music from there. “All those other people that were playing with percussion instruments, they did the same thing. They played what they thought was apropos,” Cyrille said. “I don’t remember Marion saying, ‘Stop. No. Do this, do that.’ He just accepted what was going on.”

“He just asked us to go ahead and play, and that’s what we did,” Cyrille continued. “Everybody was kind of focused on him spiritually.”

The seasoned improvisers were soon locked in on creating a cooperative musical experience. They knew how to move the musical dialogue along — where to mimic a certain rhythm, accentuate a phrase — but communicating the feeling of a Georgia afternoon required a strong leader. Interpretation is in the ears of the listener. Brown wrote extensively about his motivations, adding dimension and color to his musical portrait of Georgia.

“It’s not stagnant; it’s not boring. It takes you to where it wants you to go,” Cyrille said. “And if you’re open, you listen to it, then you go with it.”

A student looking east from the second floor of Spelman College’s Giles Hall in 1931 might glimpse serried shotgun houses with arched roofs to the north, the tight rows of homes only separated by a narrow dirt lane. Many of the houses had small front porches, fit for one or two rocking chairs. Beaver Slide, as the neighborhood came to be known, was like other impoverished areas of segregated, Depression-era Atlanta. As in similar community spaces that dotted the city, nearly eight in 10 houses didn’t have running water, lacked an indoor toilet, or both, according to a survey from the period by the Atlanta Housing Authority.

Buttermilk Bottom was an African-American neighborhood in central Atlanta, centered on the area where the Atlanta Civic Center now stands in the Old Fourth Ward.

Brown lived near Beaver Slide, which Atlanta officials razed in 1934 to create University Homes, one of the first public housing projects in the country. Years later, in “Geechee Recollections,” Brown immortalized the Buttermilk Bottom neighborhood. The Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture described Buttermilk Bottom as a “vibrant community” that was vital to Black life in Atlanta “despite harsh conditions imposed by segregation.”

“It was akin to a village,” according to the Smithsonian. “Homes had no electricity and telephones. The inhabitants used kerosene lamps and communicated by yelling out the windows to their neighbors.”

Certain sectors of Atlanta flourished during this period. Brown was 8 when, less than 2 miles east, “Gone with the Wind” premiered in a lavish, star-studded ceremony at the Loew’s Grand Theatre. But in interviews, Brown presented an image of an idyllic childhood. He seems to have grown up in a busy, loving household, surrounded by extended family.

“My parents had bourgeois aspirations. We went to the finest church — one of the finest churches on my side of town,” he said in an interview captured in his 1983 autobiography, Recollections: Essays, Drawings, Miscellanea. “Most people don’t go to church in their neighborhood; they go way across town … I used to criticize people about that because I thought it would give you a few extra minutes to sleep in the morning.”

Brown came to the alto saxophone in junior high partly because his mother had friends who played the instrument in dance bands. At a young age, he was drawn to the romantic nature of the instrument and the noble stature, in his eyes, of local performers and saxophone progenitors like Johnny Hodges.

“Most of the alto saxophone players that I knew when I was a kid were really very respectable people. They were insurance men or teachers. They had a certain savoir faire,” he recalled in his memoir.

As a kid living near the universities, he played on campus, roaming the halls instead of the playground. It seemed foreordained that Brown would enroll in Clark College, the precursor to Clark Atlanta University. After a three-year stint performing in the 1st Cavalry Army Band, a volunteer enlistment that took him to Hokkaido, Japan, he returned to Georgia to pursue a music education degree under the nationally known music pedagogue, Wayman Carver. He stayed at the university for five years. Before completing his degree, he moved to Washington, D.C., and enrolled in Howard University with an eye on law school.

“After spending two fruitless years studying at Howard University, I gave up my plans to become a civil rights attorney and decided to get back into music,” he wrote in his master’s thesis. During his time at Howard, he continued to practice saxophone and even took classical guitar lessons. There were few opportunities to perform there, so he headed to New York.

Marion Brown playing on the roof of an apartment building in New York City. “We were all inspired by the efforts of Dr. King and Malcolm X and nationalism, the re-creation of the Black identity, [We played] music that reaffirmed the identity of Black people. It was a real awakening of the spirit of what is the meaning to be Black and how that awakening was inspired by growing up in the South.” — Archie Shepp. Photo by Larry Fink

When he arrived in New York in 1962, Brown and 25-year-old tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp, who had just recorded his first album as a bandleader, immediately became close friends.

“He was a very genial guy — very warm, very intelligent. He spoke with a Southern drawl, which I found very engaging because my background and my people are from the South,” remembered Shepp.

Shepp’s “Fire Music,” released in 1965, proved to be Brown’s most mainstream introduction to the recorded world. Brown said hello with angular solos that twist and turn in blurs of notes. The bright, straightforward tone of his saxophone contrasted Shepp’s slightly belligerent, gruff sound. Even on uptempo, feverish performances, Brown’s solos maintain a low simmer, as opposed to the boiling-over bebop calisthenics of his saxophone forebears. An admirer of Dave Brubeck Quartet saxophonist Paul Desmond, Brown’s playing contains Desmond’s same sweetness and deliberate, thoughtful approach.

“I am more involved in sound texture than I am in how fast I can go from the bottom to the top, how many notes I can play per measure,” he said in his autobiography.

The two men were musically inseparable in those early New York City years when Shepp helped Brown secure a record contract with Impulse! Records. “Three for Shepp,” Brown’s first recording for a major label, pays homage to the man who integrated him into the scene and helped him earn a spot on Coltrane’s landmark “Ascension” album. Shepp said he even secured a horn for the alto player, who had traveled to New York without an instrument.

Shepp remembered Brown as a bookish intellectual, engrossed in the works of writers like Jean Toomer and Amos Tutuola, and focused on the political and civil rights struggles of the day. The two ran in a social circle that included many of the day's prominent musicians as well as the poet, writer, and critic Amiri Baraka (then known as LeRoi Jones).

“We were all inspired by the efforts of Dr. King and Malcolm X and nationalism, the re-creation of the Black identity,” Shepp said. “[We played] music that reaffirmed the identity of Black people. It was a real awakening of the spirit of what is the meaning to be Black and how that awakening was inspired by growing up in the South.”

Marion Brown plays with Kellie Jones (left) and her sister, Lisa Jones, at the home of Hettie and LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka) in the mid-’60s. Photo by Larry Fink.

Pianist Dave Burrell recorded with Brown on two of the saxophonist’s early albums, “Juba-Lee” and “Three for Shepp.”

“Every time there was a booking at the Fillmore East that featured John Coltrane’s groups, the next group down, so to speak, was a group with Marion,” Burrell recalled. “We felt like we were some kind of protégées. Marion … had a sound that I thought was demonstrating that he was an innovator in the avant garde.”

Brown also acted as a foil for some of the more tightly-wound musicians of the period. Pianist Burton Greene, who today, at age 83, is still a ball of energy even when conversing over the phone, recalled Brown as a grounding force on Greene’s 1965 debut and during subsequent gigs.

“I needed an anchor, and he was a good one because he was very quiet, very consummate about what he was doing, very focused and laid-back,” Greene said from his home in Amsterdam. “He was quiet. He was just a professional, man. He was older, and he was wiser, and I appreciated that. I learned from the cat, and I respected him.”

The saxophonist could feel a breakout around the corner, but wondered if it would come soon enough. As Brown wrote in his thesis, “My name was mentioned often as a musician with promise for the future. I began receiving attention from critics and other musicians. I began performing more often, but still for little money ... I had, to a certain extent, arrived on the jazz scene.”

Brown’s music in that period might be described as free jazz, but that loose descriptor applies to such a vast array of music that it offers little insight. Coltrane, who welcomed “free” improvisers like Brown onto the bandstand during club dates, saw little use in labels. “I myself don’t recognize the word jazz. I mean, we’re sold under this name, but to me the word doesn’t exist,” he can be heard saying on “Chasing Trane: The John Coltrane Documentary” (as voiced by Denzel Washington). “I think the main thing a musician would like to do is give a picture to the listener of the many wonderful things he knows of and senses in the universe. That's what music is to me.”

Brown left New York for Europe in 1967, searching for a rosier financial situation. He had considered returning to Atlanta, where he could find enough work to make a living playing music, but thought Europe might hold more promise.

“Before going to Europe, my interest in African music was only at the level of appreciation,” Brown wrote. “Now it grew as a result of being directly exposed not only to recordings and books but to a community of Africans large enough to have within it some very interesting musicians and performers.”

Brown recalled his European music associates thought he would stay in Europe for the rest of his life, but to him, living in Europe was always a temporary move.

“After such a long time away from my roots, I began feeling the need to go home so I could have the things that really meant more to me than being in Europe.”

He spent two years of touring and performing throughout Europe wherever the opportunity arose, returning to the States with a fiancée, Gail Linda Anderson, another Black expat. They married in August 1969, two years after they met in Paris. “I got tired of being thought of as an expatriate. I was tired of people saying that jazz musicians come to Europe to escape unemployment, racism, and to live with European women.”

They returned to Atlanta to live with Brown’s aunt and uncle, giving him a chance to reconnect after nearly a decade away from the South. Their son, Djinji, was born during this Southern hiatus while Brown gave music lessons and Anderson took photographs for the Institute of the Black World.

“I went to church every Sunday, as I did when I was growing up,” he remembered in his thesis. Brown soon moved north, with his family, to New Haven, Connecticut, for a job teaching elementary music education. The relocation meant he was close enough to New York to rekindle contacts and get back into the studio.

“Georgia Faun” is a sound of recollection mixed with ancestral lineage. It’s not nostalgia or a longing for 1930s Atlanta, but a re-creation of the feeling of the South. On his subsequent Georgia album, “Geechee Recollections,” that mood — the slow-moving tempo, the wide-open spaces — is accentuated by the drumming and rhythms of the Geechee people.

The record’s direct reference to ancestral Black residents of coastal Georgia and the inclusion of indigenous percussion instruments and rhythms focused the conversation on then-little-discussed culture. To realize this, Brown, trumpeter Smith, and a band featuring bassist James Jefferson teamed up with Ghanaian percussionist Abraham Kobena Adzenyah.

Griffin Lotson, vice chair of the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor Commission, is a seventh generation Gullah-Geechee. As a 20-something in the 1970s, he tried to distance himself from the culture, which was looked down upon as uncivilized, even in the South. He can remember rejecting the patois and hearing a constant refrain of “Boy, you’re too Geechee” in his daily life. “Geechee Recollections” shined a light, however dim, on the culture.

Lotson said he believes Brown’s ancestors came from the Congo and likely journeyed to America on the slave ship Wanderer, which docked off the coast of Georgia at Jekyll Island in November 1858. That timeline could make Brown’s grandfather part of the Geechee society that bloomed in the area.

“Wow, he was ahead of his time,” said Lotson. “It was not popular to talk too much, to do music on Geechee or Gullah, but he did. People probably didn’t understand it, but he wanted to leave a mark.”

Brown opens the album with “Once Upon a Time (A Children’s Tale),” a celebration of West African instruments and sounds — drum polyrhythms, a skipping, six-note ostinato in the bass followed by the melody, played on clarinet and muted trumpet, that feels slightly out of time. The drums maintain propulsion through the song, as the horns dance through and around the instruments.

The second tune on the album, “Karintha,” contains a recitation from Toomer’s Cane. In the 1923 novel, Toomer describes the unhurriedness of Southern life with tableaux he collected during a trip to Georgia. His words made a lifelong impression on Brown.

“Karintha” marks Toomer’s first overt appearance in Brown’s music. The poem of the same name follows a Southern girl from youth to adolescence to motherhood. On the record, Bill Hasson intones Toomer’s poetry — “her skin is like dust on the eastern horizon ... when the sun goes down” — over leaping cello lines, scattered percussion and bells, and light, pentatonic plucks on a thumb piano. On trumpet, Smith squeals and forces pinched, high notes before Brown blows long, luxuriant tones, full of vibrato, from his soprano saxophone. Redolent phrases — “supper-getting-ready songs,” “November cotton flower” — swell from the narration slowly, pushed to the fore by the background din.

Brown’s musical relationship with Smith preceded “Geechee.” The two lit the kindling of their partnership one evening in the late summer of 1970, when the young trumpeter and his wife visited Brown’s home in New Haven. The two were soon playing in churches in the area, presenting evenings of creative music on their primary horns as well as homemade instruments constructed from scrap metal. The spirit of these performances is captured on “Duets,” released in 1975.

Both were cerebral, philosophical thinkers who mapped their ideas about music in dissertations and liner notes that went beneath the surface of songs. The two also spoke about spirituality and morality. “He wasn’t a guy who went to church [anymore]; neither was I, so to speak,” Smith, 79, said. “But a deep concern for humanity was one of his major characteristics.”

Smith remembered Brown as the protective older man who treated him as a brother or even a son, a tendency of “mature, African American men who were born and raised in the South.”

Although “Geechee Recollections” is the most anthropological and traditionally straightforward of Brown’s three albums, “He saw them [all] as major works that would express his desire, what he means by being a creator,” Smith said. “Those works were dreams that were being fulfilled that he probably had for a long time.”

Spirituality floats through the entire Georgia trilogy. Writing about “Sweet Earth Flying,” Brown noted the sound structure as “something ineffably connected with Georgia, my home.” The title comes from the same Toomer book that provided so much of Brown’s inspiration. In it, Toomer envisions a Georgia summer thunderstorm, one of those here-then-gone showers experienced so often in hot weather. “Thunder blossoms gorgeously above our heads … Dripping rain like golden honey / and the sweet earth flying from the thunder.”

This final record of Brown’s Georgia exploration is the most impressionistic. Paul Bley and Muhal Richard Abrams play organ, piano, and electric piano to create a dense atmosphere for Brown. The musicians are further supported by bassist Jefferson and drummer Steve McCall. Bley opens the work with a ruminative electric piano solo, giving way to bombastic drums before the band enters. The music progresses out of time; there’s a structure but it seems dictated in the moment. Brown’s saxophone enters aggressively, with the most fire heard on any of the Georgia recordings. On its own, this section of the trilogy transports, captivates, immerses, and, like Toomer’s literature, creates a new world.

Pianist Vijay Iyer, an ECM artist who has recorded with Smith, thinks about Brown’s work from a logistical standpoint. In putting together this music, Brown is functioning more as a composer than a jazz musician from that era, he said. “Sweet Earth Flying” is not a standard record where the leader would select a band, rehearse them and then record a bunch of tunes.

“He’s self-effacing in the mix,” Iyer said. “He doesn’t even show up for several minutes. You’re like, ‘Wait, is this really a Marion Brown record?’”

Brown’s approach brings to mind Miles Davis, Iyer said. “A lot of Miles’ records from the ’70s, he’s not that prominent in them either. It’s really like you put together these very odd, unique groupings that might have multiple drummers, multiple keyboard players. … It wouldn’t really be about who’s doing what, it’s more about how is this whole environment evolving and shifting.”

In the early 1960s, while he was crafting improvised music in New York City that questioned the status quo, Brown’s Georgia neighborhood became a flashpoint for civil rights. Students began picketing, started sit-ins at local businesses, and organized marches. Leaders of the Atlanta Student Movement like Julian Bond demanded equal representation in a segregated Atlanta.

In recognition of this history, former Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed renamed the section of Fair Street on which Brown grew up Atlanta Student Movement Boulevard in 2010. Issues of segregation, equal representation, and civil rights became inextricably linked with Brown’s 1960s musical compatriots, but that legacy is infused in his Georgia work as well.

The same struggles that convinced Brown to consider civil rights law, that shaped his music in the 1960s, are unfortunately pervasive today.

“[The albums] represent this idea of liberty and justice,” trumpeter Smith said. “These pieces would be wonderful to revisit because they are talking about that same kind of Black Lives Matter as the population are talking about now.”

In the musical world, Brown’s influence has taken root beyond jazz. In 2007, guitarist Warren Defever, who performs as His Name Is Alive, released a record of chopped up Brown compositions.

“Unlike artists like John Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, or Ornette Coleman, I always felt like there wasn't one Marion Brown LP that best showed his many talents as a composer, improviser, player, and bandleader,” he said.

Defever was drawn to Brown’s music by the vocal quality of his saxophone and the compositions that used a blend of African and American music. Before releasing the album, Defever wrote to Brown for his blessing and received an enthusiastic response.

“I was terrified about the way I had disregarded the original arrangements — keys had been transposed, saxophone lines were sometimes played on trumpet, major keys were now minor,” he said. “I had taken some very serious liberties.”

In the musical world, Brown’s influence has taken root beyond jazz. “He really deserved to be better known. And it is often those we hear the least that we should listen to the most.” — Jonathan Jurion. Photo by Larry Fink.

Mac McCaughan, frontman of rock band Superchunk, discovered Brown’s music while on tour. He remembers spending hours in a van, reading The Penguin Guide to Jazz while traveling from gig to gig.

“I think for lack of a better word, Marion's music is just — human. There's a folk aspect to it and an intuitive feeling to it,” he said. “Marion's music also has something that I find brings me back again and again to lots of music — a feeling that there's something there just out of reach that I want to get to eventually by listening over and over.”

McCaughan introduced Brown to Superchunk’s audience with “Song for Marion Brown,” a four-minute rumination on fame and creativity on the 1997 album “Indoor Living.” He wrote the tune while investigating Brown’s Georgia recordings and his duets with Smith. McCaughan wanted to write a song that dug into how we, as a culture, assess creative value.

“It's about my love for the unique intellect and artistry of someone like Marion and how hard it is to be recognized if you are a unique voice in the world,” he said.

Guadeloupean pianist Jonathan Jurion paid tribute to Brown on the pianist’s debut release, “Le Temps Fou.” Jurion drew parallels between Brown’s compositions and the music of his own homeland, Gwo-Ka, an intensely rhythmic aural lexicon enslaved Africans used for secret communication that can be very free and atonal, just like Brown’s early work.

“He really deserved to be better known,” Jurion wrote in an email. “And it is often those we hear the least that we should listen to the most.”

Brown had a lasting friendship with composer Budd, whom he met in the early 1970s in California. Budd knew of Brown by reputation long before they met and was a fan of that kind of improvised music. At that first gathering, Budd played Brown “Madrigals of the Rose Angel,” and a creative partnership blossomed.

“He listened to the entire thing very quietly, and at the end he said, ‘Would you write a piece for my horn?’” said Budd, who died in December of complications from the novel coronavirus. “I didn’t think that he thought that I would actually do it.”

The result was “Bismillahi 'Rrahmani 'Rrahim,” the first track on Budd’s “The Pavilion of Dreams,” which hit the market in 1977. Brown had premiered the tune in a concert at Wesleyan University while he was pursuing his master’s degree.

“Marion just absolutely shattered everyone,” Budd said. “I mean we were all in awe of his solo, and it was just so beautiful.”

Budd knew a Marion Brown inspired by the world around him, conveying his experiences through music, words, and paintings. Brown’s memories, collected in three albums, form part of that legacy, but his impact on musicians and listeners alike stretches beyond sound. During his life, he painted, acted, made instruments, and thought deeply about art, philosophy, and culture.

“He was a great fan of Ezra Pound. And he would turn me on to Ezra Pound, not poetry but kind of thinking. How that happened I haven’t a clue, but he was a real Ezra Pound devotee,” Budd said. “He had the kind of personality that encompasses a lot of things. That, to me, is a person who’s fully alive.”

Jon Ross has worked as a freelance cultural journalist in Atlanta since 2007 writing for Downbeat and the Atlanta Journal Consitution, among others. He has degrees in music and journalism from the University of Idaho and a master's degree from Syracuse University with a concentration in jazz and pop music. Ross lives in the Morningside neighborhood of Atlanta with his wife and three sons.

Larry Fink has been working as a professional photographer for over 55 years. He’s had one-man shows at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of Modern Art, the Musée de l’Elysée in Lausanne, Switzerland, the Musée de la Photographie in Charleroi, Belgium, and more. Fink was the recipient of the Lucie Award for Documentary Photography in 2017, and in 2015 was awarded the International Center for Photography (ICP) Infinity Award for Lifetime Fine Art Photography. He is the recipient of two John Simon Guggenheim Fellowships and two National Endowment for the Arts, Individual Photography Fellowships. See his online portfolio here.